The actual risk causing the injury to the plaintiff was explicitly identified in the release and used by the court as proof it was a risk of skiing and snowboarding. If it was in the release, then it was a risk.

Posted: September 17, 2018 Filed under: Assumption of the Risk, California, Release (pre-injury contract not to sue), Ski Area, Skiing / Snow Boarding | Tags: assumption of the risk, Groomer, grooming, Mammoth, Mammoth Mountain Ski Area, Mammoth Mt. Ski Area, Mammoth Mt. Ski Area LLC, Release, Season Pass, Season Pass Release, Ski, ski area, Ski Resort, skiing, snowboarding, Snowcat, Summary judgment, tiller Leave a commentPlaintiff hit a snowcat and was severely injured when she was sucked under the tiller. Mammoth Mountain Ski Area was not liable because of the release and snowcats on the mountain are an inherent risk of skiing and snowboarding.

Willhide-Michiulis v. Mammoth Mt. Ski Area, LLC, 2018 Cal. App. Unpub. LEXIS 4363

State: California, Court of Appeal of California, Third Appellate District

Plaintiff: Kathleen Willhide-Michiulis et al (and her husband Bruno Michiulis)

Defendant: Mammoth Mountain Ski Area, LLC

Plaintiff Claims: negligence, gross negligence and loss of consortium

Defendant Defenses: Assumption of the risk and release

Holding: for the defendant ski area Mammoth Mt. Ski Area

Year: 2018

Summary

When skiing or snowboarding you assume the risk of seeing a snowcat grooming on the slopes in California. If you run into a snowcat and get sucked into the tiller you have no lawsuit against the ski area.

A snowcat at Mammoth Mountain Ski Area is a great big red slow-moving machine with flashing lights and sirens. They are hard to miss, so therefore they are something you assume the risk when on the slopes.

Facts

The injury suffered by the plaintiff and how it occurred is gruesome. She hit a snowcat while snowboarding and fell between the cat and the tiller. Before the cat could stop she was run over and entangled in the tiller eventually losing one leg and suffering multiple other injuries.

Plaintiff Kathleen Willhide-Michiulis was involved in a tragic snowboarding accident at Mammoth Mountain Ski Area. On her last run of the day, she collided with a snowcat pulling a snow-grooming tiller and got caught in the tiller. The accident resulted in the amputation of her left leg, several skull fractures and facial lacerations, among other serious injuries

The plaintiff was snowboarding on her last run of the night. She spotted the snow cat 150 feet ahead of her on the run. When she looked up again, she collided with the snowcat.

While Willhide-Michiulis rode down mambo, she was in control of her snowboard and traveling on the left side of the run. She saw the snowcat about 150 feet ahead of her on the trail. It was traveling downhill and in the middle of the run. Willhide-Michiulis initiated a “carve” to her left to go further to the left of the snowcat. When she looked up, the snowcat had “cut off her path” and she could not avoid a collision. Willhide-Michiulis hit the back-left corner of the snowcat and her board went into the gap between the tracks of the snowcat and the tiller. Willhide-Michiulis was then pulled into the tiller.

The defendant Mammoth Mountain Ski Area posted warning signs at the top and bottom of every run warning that snowcats and other vehicles may be on the runs. The season pass releases the plaintiff, and her husband signed also recognized the risk of snowcats and identified them as such.

Further, in Willhide-Michiulis’s season-pass agreement, she acknowledged she understood “the sport involves numerous risks including, but not limited to, the risks posed by variations in terrain and snow conditions, . . . unmarked obstacles, . . . devices, . . . and other hazards whether they are obvious or not. I also understand that the sport involves risks posed by loss of balance . . . and collisions with natural and man-made objects, including . . . snow making equipment, snowmobiles and other over-snow vehicles.

The trial court concluded the plaintiff assumed the risks of her injury and granted the ski area motion for summary judgment. The plaintiff appealed that decision, and this appellate decision is the result of that appeal.

Analysis: making sense of the law based on these facts.

The decision included a massive recounting of the facts of the case both before the analysis and throughout it. Additionally, the court reviewed several issues that are not that important here, whether the trial court properly dismissed the plaintiff’s expert opinions and whether or not the location of the case was proper.

Releases in California are evolving into proof of express assumption of the risk. The court reviewed the issues of whether Mammoth met is burden of showing the risks the plaintiff assumed were inherent in the sport of snowboarding. The facts in the release signed by the plaintiff supported that assumption of the risk defense and was pointed out by the court as such.

…plaintiffs signed a season-pass agreement, which included a term releasing Mammoth from liability “for any damage, injury or death . . . arising from participation in the sport or use of the facilities at Mammoth regardless of cause, including the ALLEGED NEGLIGENCE of Mammoth.” The agreement also contained a paragraph describing the sport as dangerous and involving risks “posed by loss of balance, loss of control, falling, sliding, collisions with other skiers or snowboarders and collisions with natural and man-made objects, including trees, rocks, fences, posts, lift towers, snow making equipment, snowmobiles and other over-snow vehicles.”

California courts also look at the assumption of risk issue not as a defense, but a doctrine that releases the defendant of its duty to the plaintiff.

“While often referred to as a defense, a release of future liability is more appropriately characterized as an express assumption of the risk that negates the defendant’s duty of care, an element of the plaintiff’s case.” Express assumption of risk agreements are analogous to the implied primary assumption of risk doctrine. “The result is that the defendant is relieved of legal duty to the plaintiff; and being under no duty, he cannot be charged with negligence.””

The court then is not instructed to look at the activity to see the relationship of the parties or examine the activity that caused the plaintiff’s injuries. The question becomes is the risk of injury the plaintiff suffered inherent in the activity in which the plaintiff was participating. The issue then becomes a question solely for the courts as in this case, does the scope of the release express the risk relieving the defendant of any duty to the plaintiff.

After the judge makes that decision then the question of whether or not the actions of the defendant rose to the level of gross negligence is reviewed. “The issue we must determine here is whether, with all facts and inferences construed in plaintiffs’ favor, Mammoth’s conduct could be found to constitute gross negligence.

Ordinary or simple negligence is a “failure to exercise the degree of care in a given situation that a reasonable person under similar circumstances would employ to protect others from harm.”

“‘”[M]ere nonfeasance, such as the failure to discover a dangerous condition or to perform a duty,”‘ amounts to ordinary negligence. However, to support a theory of ‘”[g]ross negligence,”‘ a plaintiff must allege facts showing ‘either a “‘”want of even scant care”‘” or “‘”an extreme departure from the ordinary standard of conduct.”‘”[G]ross negligence’ falls short of a reckless disregard of consequences, and differs from ordinary negligence only in degree, and not in kind. . . .”‘”

When looking at gross negligence, the nature of the sport comes back into the evaluation.

“‘[A] purveyor of recreational activities owes a duty to a patron not to increase the risks inherent in the activity in which the patron has paid to engage.'” Thus, in cases involving a waiver of liability for future negligence, courts have held that conduct that substantially or unreasonably increased the inherent risk of an activity or actively concealed a known risk could amount to gross negligence, which would not be barred by a release agreement.

Skiing and snowboarding have a long list of litigated risks that are inherent in the sport and thus assumed by the plaintiff or better, to which the defendant does not owe the plaintiff a duty.

There the plaintiff argued the snow groomer was not an assumed risk. The court eliminated that argument by pointing out the plaintiff had signed a release which pointed out to the plaintiff that one of the risks she could encounter was a snow groomer on the slopes.

The main problem with plaintiffs’ argument that common law has not recognized collisions with snow-grooming equipment as an inherent risk of skiing, is that plaintiffs’ season-pass agreement did. When signing their season-pass agreement, both Willhide-Michiulis and her husband acknowledged that skiing involved the risk of colliding with “over-snow vehicles.” Willhide-Michiulis testified she read the agreement but did not know an “over-snow vehicle” included a snowcat. Plaintiffs, however, did not argue in the trial court or now on appeal that this term is ambiguous or that the parties did not contemplate collisions with snowcats as a risk of snowboarding. “Over-snow vehicles” is listed in the contract along with “snow making equipment” and “snowmobiles,” indicating a clear intent to include any vehicle used by Mammoth for snow maintenance and snow travel.

The court went on to find case law that supported the defense that snow groomers were a risk of skiing and boarding, and it was a great big slow moving bright-red machine that made it generally unavoidable.

Further, the snowcat Willhide-Michiulis collided with is large, bright red, and slow-moving, making it generally avoidable by those around it. Indeed, Willhide-Michiulis testified that she saw the snowcat about 150 feet before she collided with it. Although she claims the snowcat cut off her path, the snowcat was traveling less than ten miles an hour before standing nearly motionless while turning onto Old Boneyard Road downhill from Willhide- Michiulis.

Even if there were no warning signs, nothing on the maps of the ski area, nothing in the release, once the plaintiff spotted the snowcat the responsibility to avoid the snowcat fell on her.

The appellate court upheld the trial courts motion for summary judgement in favor of the defendant ski area Mammoth Mountain.

So Now What?

The California Appellate Court took 11 pages to tell the plaintiff if you see a big red slow-moving machine on the ski slopes to stay away from it.

What is also interesting is the evolution of the law in California from a release being a contractual pre-injury agreement not to sue to proof that the defendant did not owe a duty to the plaintiff because she assumed the risk.

Besides, how do you miss, let alone ski or snowboard into a big red slow-moving machine with flashing lights and sirens on a ski slope?

What do you think? Leave a comment.

Copyright 2017 Recreation Law (720) 334 8529

If you like this let your friends know or post it on FB, Twitter or LinkedIn

Author: Outdoor Recreation Insurance, Risk Management and Law

Facebook Page: Outdoor Recreation & Adventure Travel Law

Email: Rec-law@recreation-law.com

By Recreation Law Rec-law@recreation-law.com James H. Moss

#AdventureTourism, #AdventureTravelLaw, #AdventureTravelLawyer, #AttorneyatLaw, #Backpacking, #BicyclingLaw, #Camps, #ChallengeCourse, #ChallengeCourseLaw, #ChallengeCourseLawyer, #CyclingLaw, #FitnessLaw, #FitnessLawyer, #Hiking, #HumanPowered, #HumanPoweredRecreation, #IceClimbing, #JamesHMoss, #JimMoss, #Law, #Mountaineering, #Negligence, #OutdoorLaw, #OutdoorRecreationLaw, #OutsideLaw, #OutsideLawyer, #RecLaw, #Rec-Law, #RecLawBlog, #Rec-LawBlog, #RecLawyer, #RecreationalLawyer, #RecreationLaw, #RecreationLawBlog, #RecreationLawcom, #Recreation-Lawcom, #Recreation-Law.com, #RiskManagement, #RockClimbing, #RockClimbingLawyer, #RopesCourse, #RopesCourseLawyer, #SkiAreas, #Skiing, #SkiLaw, #Snowboarding, #SummerCamp, #Tourism, #TravelLaw, #YouthCamps, #ZipLineLawyer, #RecreationLaw, #OutdoorLaw, #OutdoorRecreationLaw, #SkiLaw,

Willhide-Michiulis v. Mammoth Mt. Ski Area, LLC, 2018 Cal. App. Unpub. LEXIS 4363

Posted: September 12, 2018 Filed under: Assumption of the Risk, California, Release (pre-injury contract not to sue), Ski Area, Skiing / Snow Boarding | Tags: collided, Collision, conditions, declarations, driver's, Driving, expert testimony, extreme departure, grooming, Gross negligence, industry standard, Inherent Risk, mambo, Mammoth, Mammoth Mountain Ski Area, Mammoth Mt. Ski Area, Mammoth Mt. Ski Area LLC, Mountain, ordinary standard, plaintiffs', Risks, Season Pass, skier's, skiing, Snow, snow grooming, snow-grooming vehicle, snowboarding, Snowcat, Sport, Summary judgment, tiller, Trial court, Venue, Warning Leave a commentWillhide-Michiulis v. Mammoth Mt. Ski Area, LLC

Court of Appeal of California, Third Appellate District

June 27, 2018, Opinion Filed

C082306

2018 Cal. App. Unpub. LEXIS 4363 *; 2018 WL 3134581KATHLEEN WILLHIDE-MICHIULIS et al., Plaintiffs and Appellants, v. MAMMOTH MOUNTAIN SKI AREA, LLC, Defendant and Respondent.

Notice: NOT TO BE PUBLISHED IN OFFICIAL REPORTS. CALIFORNIA RULES OF COURT, RULE 8.1115(a), PROHIBITS COURTS AND PARTIES FROM CITING OR RELYING ON OPINIONS NOT CERTIFIED FOR PUBLICATION OR ORDERED PUBLISHED, EXCEPT AS SPECIFIED BY RULE 8.1115(b). THIS OPINION HAS NOT BEEN CERTIFIED FOR PUBLICATION OR ORDERED PUBLISHED FOR THE PURPOSES OF RULE 8.1115.

Subsequent History: The Publication Status of this Document has been Changed by the Court from Unpublished to Published July 18, 2018 and is now reported at 2018 Cal.App.LEXIS 638.

Ordered published by, Reported at Willhide-Michiulis v. Mammoth Mountain Ski Area, LLC, 2018 Cal. App. LEXIS 638 (Cal. App. 3d Dist., June 27, 2018)

Prior History: [*1] Superior Court of Mono County, No. CV130105.

Judges: Robie, Acting P. J.; Murray, J., Duarte, J. concurred.

Opinion by: Robie, Acting P. J.

Plaintiff Kathleen Willhide-Michiulis was involved in a tragic snowboarding accident at Mammoth Mountain Ski Area. On her last run of the day, she collided with a snowcat pulling a snow-grooming tiller and got caught in the tiller. The accident resulted in the amputation of her left leg, several skull fractures and facial lacerations, among other serious injuries. She and her husband, Bruno Michiulis, appeal after the trial court granted defendant Mammoth Mountain Ski Area‘s (Mammoth) motion for summary judgment finding the operation of the snowcat and snow-grooming tiller on the snow run open to the public was an inherent risk of snowboarding and did not constitute gross negligence. Plaintiffs contend the trial court improperly granted Mammoth’s motion for summary judgment and improperly excluded the expert declarations plaintiffs submitted to oppose the motion. They also assert the trial court improperly denied their motion to transfer venue to Los Angeles County.

We conclude the trial court did not abuse its discretion by excluding the expert declarations. Further, [*2] although snowcats and snow-grooming tillers are capable of causing catastrophic injury, as evidenced by Willhide-Michiulis’s experience, we conclude this equipment is an inherent part of the sport of snowboarding and the way in which the snowcat was operated in this case did not rise to the level of gross negligence. Because of this conclusion, the trial court properly granted Mammoth’s summary judgment motion based on the liability waiver Willhide-Michiulis signed as part of her season-pass agreement. With no pending trial, plaintiffs cannot show they were prejudiced by the court’s denial of their motion to transfer venue; thus we do not reach the merits of that claim. Accordingly, we affirm.

FACTUAL AND PROCEDURAL BACKGROUND

I

The Injury

Mammoth owns and operates one of the largest snowcat fleets in the United States to groom snow and maintain snow runs throughout Mammoth Mountain Ski Area. A snowcat is a large snow-grooming vehicle — 30 feet long and 18 feet wide. It has five wheels on each side of the vehicle that are enclosed in a track. In front of the snowcat is a plow extending the width of the snowcat. In back is a 20-foot wide trailer containing a tiller. A tiller “spins at a [*3] high [speed] br[e]aking up the snow and slightly warming it and allowing it to refreeze in a firm skiable surface.” Mammoth strives not to have snowcats operating when the resort is open to the public; however, it may be necessary at times. Mammoth’s grooming guide instructs drivers that generally snowcats are operated at night or in areas closed to the public, except during: (1) emergency operations, (2) extremely heavy snow, or (3) transportation of personnel or materials. If a driver “must be on the mountain while the public is present,” however, the snowcat’s lights, safety beacon, and audible alarm must be on. The guide further directs drivers not to operate the tiller if anyone is within 50 feet or if on a snow run open to the public. In another section, the guide directs drivers not to operate the snowcat’s tiller when anyone is within 150 feet and “[n]ever . . . when the skiing public is present.”

Although the grooming guide directs drivers not to use the tiller on snow runs open to the public, there are exceptions to these rules. Snowcats use two large tracks, instead of wheels, to travel on the snow. If the tiller is not running, then the snowcat leaves behind berms and holes created by the [*4] tracks, also known as track marks. Mammoth’s grooming guide explains that “[t]rack marks are not acceptable anywhere on the mountain and back-ups or extra passes should be used to remove them.” Track marks are not safe for the skiing public, so whenever the snowcat is justified to be on an open run, drivers commonly operate the tiller to leave behind safe conditions.

In fact, it is common for skiers and snowboarders to chase snowcats that operate on public snow runs. For example, Taylor Lester, a Mammoth season-pass holder, has seen snowcats with tillers operate on snow runs open to the public. She, her friends, and her family, commonly ride close behind these snowcats so they can take advantage of the freshly tilled snow the snowcats produce. Freshly-tilled snow is considered desirable and “more fun” because it has not been tarnished by other skiers.

There is a blind spot in the snowcat created by the roll cage in the cab of the vehicle. This blind spot is mitigated by the driver using the mirrors of the snowcat and turning his or her head to look out the windows. Snowcats are also equipped with turn signals.

At the top and bottom of every chair lift, Mammoth posts signs warning of the presence [*5] of snowcats throughout the resort and on snow runs. Mammoth also includes these warnings in trail maps. Further, in Willhide-Michiulis’s season-pass agreement, she acknowledged she understood “the sport involves numerous risks including, but not limited to, the risks posed by variations in terrain and snow conditions, . . . unmarked obstacles, . . . devices, . . . and other hazards whether they are obvious or not. I also understand that the sport involves risks posed by loss of balance . . . and collisions with natural and man-made objects, including . . . snow making equipment, snowmobiles and other over-snow vehicles.” Willhide-Michiulis further agreed to release Mammoth from liability “for any damage, injury or death to me and/or my child arising from participation in the sport or use of the facilities at Mammoth regardless of cause, including the ALLEGED NEGLIGENCE of Mammoth.”

On March 25, 2011, Clifford Mann, the general manager of mountain operations, had to dig out various buildings using a snowcat during Mammoth’s hours of operation because between 27 and 44 inches of snow fell the night before. At approximately 3:15 p.m., Mann was digging out a building when a Mammoth employee [*6] called to ask him to fill in a hole she had created with her snowmobile on Old Boneyard Road. Less than an hour before her call, the employee had been driving her snowmobile on the unmarked service road and got it stuck in the snow. She called for assistance and she and another Mammoth employee dug out the snowmobile. Once the machine had been dug out of the snow, there was too big of a hole for her and her coworker to fill in. They decided to call Mann to have him fill in the hole with the snowcat because it was near the end of the day and the hole was a safety hazard for all other snowmobiles that would use the service road at closing. Mann agreed and drove his snowcat with the tiller running to Old Boneyard Road, which branched off of the bottom of mambo snow run. Before leaving for the Old Boneyard Road location, Mann turned on the snowcat’s warning beacon, lights, and audible alarm.

Around this same time, Willhide-Michiulis, a Mammoth season-pass holder, and her brother went for their last snowboard run of the day while Willhide-Michiulis’s husband went to the car. It was a clear day and Willhide-Michiulis and her brother split up after getting off the chair lift. Willhide-Michiulis [*7] snowboarded down mambo, while her brother took a neighboring run. While Willhide-Michiulis rode down mambo, she was in control of her snowboard and traveling on the left side of the run. She saw the snowcat about 150 feet ahead of her on the trail. It was traveling downhill and in the middle of the run. Willhide-Michiulis initiated a “carve” to her left to go further to the left of the snowcat. When she looked up, the snowcat had “cut off her path” and she could not avoid a collision. Willhide-Michiulis hit the back left corner of the snowcat and her board went into the gap between the tracks of the snowcat and the tiller. Willhide-Michiulis was then pulled into the tiller.

Mann did not use a turn signal before initiating the turn onto Old Boneyard Road. Before the collision, Mann had constantly been checking around the snowcat for people by utilizing the snowcat’s mirrors and by looking over his shoulders and through the windows. The snowcat did not have a speedometer, but Mann thought he was going less than 10 miles an hour. When he had nearly completed the turn from lower mambo onto Old Boneyard Road, Mann saw a “black flash” in his rearview mirror. He immediately stopped the snowcat, [*8] which also stopped the tiller.

Mann got out of the snowcat and lifted the protective flap to look under the tiller. He saw Willhide-Michiulis stuck in the tiller and called for help. When help arrived, it took 30 minutes to remove Willhide-Michiulis from the tiller. She suffered a near-complete amputation of her left leg above the knee, which doctors amputated in a subsequent surgery. Her right leg sustained multiple fractures and lacerations, and she dislocated her right hip. The tiller also struck Willhide-Michiulis’s face, leaving multiple facial fractures and lacerations.

II

Plaintiffs’ Suit

Plaintiffs initially filed suit against Mammoth and Kassbohrer All Terrain Vehicles, the manufacturer of the snowcat and tiller, in Los Angeles County.1 As to Mammoth, plaintiffs alleged breach of contract, gross negligence, negligence, and loss of consortium. Venue was later transferred to Mono County, where the trial court dismissed multiple causes of action pertaining to Mammoth.2 The operative complaint alleges two causes of action against Mammoth — gross negligence and loss of consortium. At the same time plaintiffs filed the operative complaint, they also filed a motion to transfer venue back [*9] to Los Angeles County because it was more convenient for the parties and because plaintiffs could not receive a fair trial in Mono County. The trial court denied plaintiffs’ motion to transfer venue without prejudice and we denied the petition for writ of mandate plaintiffs filed challenging that ruling.

Mammoth later moved for summary judgment on the two remaining causes of action arguing that plaintiffs’ case was barred by the primary assumption of risk doctrine and the express assumption of risk agreement Willhide-Michiulis signed as part of her season-pass contract. The court agreed and granted Mammoth’s motion for summary judgment finding primary assumption of risk and the waiver in Willhide-Michiulis’s season-pass agreement barred plaintiffs relief. It found there was no dispute over the material facts of plaintiffs’ claims and that Willhide-Michiulis was injured when “she fell and slid under a [Mammoth] operated snowcat and was caught in the operating tiller. [Willhide-Michiulis] was snowboarding on an open run as the snowcat was operating on the same run. It appears that the collision occurred as the snowcat operator was negotiating a left turn from the run to the service road.” [*10] It also found that accepting plaintiffs’ factual allegations as true, i.e., Mann operated a snowcat and tiller on an open run, he failed to use a turn signal when making a sharp left turn from the center of the run, he failed to warn skiers of his presence, and no signs marked the existence of Old Boneyard Road — plaintiffs could not show Mammoth was grossly negligent or lacked all care because Mann took several safety precautions while driving the snowcat, and warning signs were posted throughout Mammoth Mountain, on trail maps, and in Willhide-Michiulis’s season-pass contract. Because plaintiffs could not show gross negligence, the waiver of liability they signed as part of their season-pass agreement barred recovery.

The court further found plaintiffs’ factual allegations did not support a finding that Mann’s conduct increased the inherent risks of snowboarding and, in fact, colliding with snow-grooming equipment is an inherent risk of the sport. Citing Souza v. Squaw Valley Ski Corp. (2006) 138 Cal.App.4th 262, 41 Cal. Rptr. 3d 389, the court explained snowcats are plainly visible and generally avoidable and serve as their own warning sign because they are an obvious danger. The snowcat is equally obvious when it is moving as when it is stationary. Thus, the [*11] primary assumption of risk doctrine also barred plaintiffs from recovery.

The court also excluded the declarations of three experts plaintiffs attached to their opposition to dispute Mammoth’s claim that it did not act with gross negligence. The first expert, Michael Beckley, worked in the ski industry for 25 years and was an “expert of ski resort safety and snow cat safety.” He held multiple positions in the industry, including ski instructor, snowcat driver, and director of mountain operations. Beckley based his opinions on the topography of the snow run, Mammoth’s snow grooming manual and snow grooming equipment, and accounts of Mann’s conduct while driving the snowcat. He opined the operation of a snowcat on an open run with its tiller running was “extremely dangerous,” “an extreme departure from an ordinary standard of conduct,” and “violate[d] the industry standard.” He believed Mann increased the risk of injury to skiers and violated industry standards by driving down the middle of a snow run and failing to signal his turn. Mammoth’s failure to close the snow run, provide spotters, or comply with its own safety rules, Beckley declared, violated industry standards and the ordinary standard [*12] of conduct.

Plaintiffs’ second expert, Eric Deyerl, was a mechanical engineer for over 20 years, with a specialization in vehicle dynamics and accident reconstruction. In forming his opinions, Deyerl inspected the snow run and snowcat equipment and relied on photographs and various accounts of the incident. Relying on those accounts, Deyerl opined that the circumstances leading to Willhide-Michiulis’s collision were different than those related by eyewitnesses. Deyerl believed that before initiating his turn, Mann failed to activate his turn signal, monitor his surroundings, and verify that he was clear — especially in the blind spot at the back left portion of the snowcat. No signs indicated the existence of Old Boneyard Road, and skiers like Willhide-Michiulis would not know to expect a snowcat to stop and turn from the middle of the snow run. All of these circumstances in isolation and together increased “the potential for a collision” and the risk of injury. Deyerl also disputed the accounts of eyewitnesses to Willhide-Michiulis’s collision with the snowcat.

The third expert, Brad Avrit, was a civil engineer who specialized in evaluating “safety practices and safety issues.” He was [*13] also an “avid skier for over thirty years.” He based his opinions on the topography of the snow run, Mammoth’s snow grooming manual and equipment, and accounts of Mann’s driving. Avrit opined that operating a snowcat on an open snow run with an active tiller was “an extreme departure from the ordinary standard of conduct that reasonable persons would follow in order to avoid injury to others.” He also believed Mann’s conduct of failing to drive down the left side of the snow run, failing to monitor his surroundings, and failing to signal his left turn or verify he was clear to turn, “increase[d] the risk of collision and injury.” Avrit also thought the risk to skiers was increased by Mammoth’s failure to either close the snow run or use spotters while operating the snowcat when open to the public, or alternatively waiting the 30 minutes until the resort was closed to fix the hole on Old Boneyard Road.

Mammoth lodged both general and specific objections to these declarations. Generally, Mammoth asserted the experts’ opinions were irrelevant to the assumption of risk and gross negligence legal determinations before the court, the opinions lacked proper foundation, and the opinions were improper [*14] conclusions of law. Specifically, Mammoth objected to several paragraphs of material on predominantly the same grounds. Finding the experts’ opinions irrelevant and citing Towns v. Davidson (2007) 147 Cal.App.4th 461, 54 Cal. Rptr. 3d 568 (Towns), the trial court sustained Mammoth’s general objections and numerous specific objections.

DISCUSSION

I

The Court Properly Granted Mammoth’s Motion For Summary Judgment

Plaintiffs contend the trial court improperly granted Mammoth’s motion for summary judgment. They first contend the trial court abused its discretion when excluding their experts’ declarations, and thus improperly ruled on Mammoth’s motion without considering relevant evidence. They also contend primary assumption of risk does not apply because Mann’s negligent driving and operation of a tiller on an open run increased the inherent risks associated with snowboarding. Further, plaintiffs argue these same facts establish Mammoth’s conduct was grossly negligent and fell outside of the liability waiver Willhide-Michiulis signed as part of her season-pass agreement.

We conclude the trial court did not abuse its discretion when excluding plaintiffs’ experts’ declarations. Additionally, plaintiffs cannot show Mammoth was grossly negligent and violated [*15] the terms of the release of liability agreement found in Willhide-Michiulis’s season-pass contract. Because the express assumption of risk in the release applies, we need not consider the implied assumption of risk argument also advanced by plaintiffs. (Vine v. Bear Valley Ski Co. (2004) 118 Cal.App.4th 577, 590, fn. 2, 13 Cal. Rptr. 3d 370; Allan v. Snow Summit, Inc. (1996) 51 Cal.App.4th 1358, 1374-1375, 59 Cal. Rptr. 2d 813; Allabach v. Santa Clara County Fair Assn. (1996) 46 Cal.App.4th 1007, 1012-1013, 54 Cal. Rptr. 2d 330.)

A

The Court Did Not Abuse Its Discretion When Excluding The Expert Declarations Attached To Plaintiffs’ Opposition

As part of their argument that the court improperly granted Mammoth’s motion for summary judgment, plaintiffs contend the trial court abused its discretion when excluding the expert declarations attached to their opposition. Specifically, plaintiffs argue expert testimony was appropriate under Kahn v. East Side Union High School Dist. (2003) 31 Cal.4th 990, 4 Cal. Rptr. 3d 103, 75 P.3d 30, because “the facts here certainly warrant consideration of the expert testimony on the more esoteric subject of assessing whether a negligently-driven snowcat is an inherent risk of recreational skiing.” Mammoth counters that the evidence was properly excluded because it was irrelevant and “offered opinions of legal questions of duty for the court to decide.” We agree with Mammoth.

“Generally, a party opposing a motion for summary judgment may use declarations by an expert to raise a triable issue of fact on an element of the [*16] case provided the requirements for admissibility are established as if the expert were testifying at trial. [Citations.] An expert’s opinion is admissible when it is ‘[r]elated to a subject that is sufficiently beyond common experience that the opinion of an expert would assist the trier of fact . . . .’ [Citation.] Although the expert’s testimony may embrace an ultimate factual issue [citation], it may not contain legal conclusions.” (Towns, supra, 147 Cal.App.4th at p. 472.)

“In the context of assumption of risk, the role of expert testimony is more limited. ‘It is for the court to decide whether an activity is an active sport, the inherent risks of that sport, and whether the defendant has increased the risks of the activity beyond the risks inherent in the sport.’ [Citation.] A court in its discretion could receive expert factual opinion to inform its decision on these issues, particularly on the nature of an unknown or esoteric activity, but in no event may it receive expert evidence on the ultimate legal issues of inherent risk and duty.” (Towns, supra, 147 Cal.App.4th at pp. 472-473.)

In Kahn, the plaintiff was a 14-year-old member of a school swim team who broke her neck after diving in shallow water. (Kahn v. East Side Union High School Dist., supra, 31 Cal.4th at p. 998.) Her coach had previously assured her she would not have to dive [*17] at meets and she never learned how to dive in shallow water. Minutes before a meet, however, the coach told the plaintiff she would have to dive and threatened to kick her off the team if she refused. With the help of some teammates, the plaintiff tried a few practice dives but broke her neck on the third try. She sued based on negligent supervision and training. (Ibid.)

The court determined the case could not be resolved on summary judgment as there was conflicting evidence whether the coach had provided any instruction or, if so, whether that instruction followed the recommended training sequence, and whether plaintiff was threatened into diving. (Kahn v. East Side Union High School Dist., supra, 31 Cal.4th at pp. 1012-1013.) The court concluded the trial court was not compelled to disregard the opinions of a water safety instructor about the proper training a swimmer requires before attempting a racing dive in shallow water. (Id. at pp. 999, 1017.) In so ruling, the Kahn court stated, “[c]ourts ordinarily do not consider an expert’s testimony to the extent it constitutes a conclusion of law [citation], but we do not believe that the declaration of the expert in the present case was limited to offering an opinion on a conclusion of law. We do not rely upon expert opinion testimony to [*18] establish the legal question of duty, but ‘we perceive no reason to preclude a trial court from receiving expert testimony on the customary practices in an arena of esoteric activity for purposes of weighing whether the inherent risks of the activity were increased by the defendant’s conduct.'” (Id. at p. 1017.) Thus, while the Kahn court did not preclude the trial court from considering expert testimony about the “‘customary practices in an arena of esoteric activity,'” it did not mandate a court to consider it either.

Here, plaintiffs argue their experts’ declarations were necessary to inform the trial court of the “more esoteric subject” of whether Mann’s negligent driving of the snowcat increased the inherent risks of recreational snowboarding. The problem with plaintiffs’ argument is that the experts’ declarations did not inform the court “‘on the customary practices'” of the esoteric activity of snowcat driving. (See Kahn v. East Side Union High School Dist., supra, 31 Cal.4th at p. 1017.) While stating that Mann and Mammoth violated industry standards and increased the potential for collision, no expert outlined what the industry standards were for operating a snowcat and thus provided no context for the trial court to determine the legal question of duty. The [*19] expert in Kahn provided this type of context by declaring the proper procedures for training swimmers to dive, making it so the trial court could compare the defendant’s conduct to the industry standard. (Kahn, at pp. 999.) The declarations here merely repeated the facts contained in the discovery materials and concluded the risk of injury and collision was increased because of those facts.

The conclusory statements in the expert declarations make plaintiffs’ case like Towns, where the trial court did not abuse its discretion when excluding an expert’s opinion. (Towns, supra, 147 Cal.App.4th at pp. 472-473.) In Towns, the plaintiff sued the defendant after he collided with her on a ski run. (Id. at p. 465.) In opposition to the defendant’s motion for summary judgment, the plaintiff submitted the declaration of her expert, a member of the National Ski Patrol and a ski instructor. (Id. at pp. 466, 471-472.) In his declaration, the expert opined that the defendant’s behavior was reckless and “‘outside the range of the ordinary activity involved in the sport of skiing.'” (Id. at p. 472.)

The trial court excluded the declaration in its entirety and granted the motion for summary judgment. The appellate court affirmed explaining, “[t]he nature and risks of downhill skiing are commonly understood, the [*20] demarcation of any duty owed is judicially defined, and, most significantly, the facts surrounding the particular incident here are not in dispute. Thus, the trial court was deciding the issue of recklessness as a matter of law.” (Towns, supra, 147 Cal.App.4th at pp. 472-473.)

The court also noted the expert’s declaration “added nothing beyond declaring the undisputed facts in his opinion constituted recklessness. In short, he ‘was advocating, not testifying.’ [Citation.] He reached what in this case was an ultimate conclusion of law, a point on which expert testimony is not allowed. [Citation.] ‘Courts must be cautious where an expert offers legal conclusions as to ultimate facts in the guise of an expert opinion.’ [Citation.] This is particularly true in the context of assumption of risk where the facts are not in dispute.” (Towns, supra, 147 Cal.App.4th at p. 473.)

Like the expert in Towns, plaintiffs’ experts only provided ultimate conclusions of law. Although Beckley declared to be an expert in snowcat safety, he shed no light on the subject except to say Mann’s conduct was “an extreme departure from an ordinary standard of conduct,” and “violate[d] the industry standard.” Similarly, Avrit, who was an expert in evaluating safety practices, did nothing more than declare [*21] that Mann’s driving and Mammoth’s grooming practices “increase[d] the risk of collision and injury.” Deyerl, an expert in accident reconstruction, disputed the accounts of percipient witnesses and declared Mann’s driving and Mammoth’s grooming practices increased “the potential for a collision” and the risk of injury. In short, plaintiffs’ experts provided irrelevant opinions more akin to “‘advocating, not testifying.'” (Towns, supra, 147 Cal.App.4th at p. 473.) Thus, the court did not abuse its discretion when excluding the expert declarations attached to plaintiffs’ opposition.

B

Summary Judgment Was Proper

We review a trial court’s grant of summary judgment de novo. (Dore v. Arnold Worldwide, Inc. (2006) 39 Cal.4th 384, 388-389, 46 Cal. Rptr. 3d 668, 139 P.3d 56.) “In performing our de novo review, we must view the evidence in a light favorable to [the] plaintiff as the losing party [citation], liberally construing [the plaintiff’s] evidentiary submission while strictly scrutinizing [the] defendant[‘s] own showing, and resolving any evidentiary doubts or ambiguities in [the] plaintiff’s favor.” (Saelzler v. Advanced Group 400 (2001) 25 Cal.4th 763, 768-769, 107 Cal. Rptr. 2d 617, 23 P.3d 1143.)

Summary judgment is proper when “all the papers submitted show that there is no triable issue as to any material fact and that [defendant] is entitled to a judgment as a matter of law.” (Code Civ. Proc., § 437c, subd. (c).) A defendant moving for summary judgment meets [*22] its burden of showing there is no merit to a cause of action by showing one or more elements of the cause of action cannot be established or there is a complete defense to that cause of action. (Code Civ. Proc., § 437c, subd. (p)(2).) Once the defendant has made the required showing, the burden shifts back to the plaintiff to show a triable issue of one or more material facts exists as to that cause of action or defense. (Aguilar v. Atlantic Richfield Co. (2001) 25 Cal.4th 826, 849, 853, 107 Cal. Rptr. 2d 841, 24 P.3d 493.)

1

Mammoth Met Its Burden Of Showing There Was No Merit To Plaintiffs’ Claim

As described, plaintiffs signed a season-pass agreement, which included a term releasing Mammoth from liability “for any damage, injury or death . . . arising from participation in the sport or use of the facilities at Mammoth regardless of cause, including the ALLEGED NEGLIGENCE of Mammoth.” The agreement also contained a paragraph describing the sport as dangerous and involving risks “posed by loss of balance, loss of control, falling, sliding, collisions with other skiers or snowboarders and collisions with natural and man-made objects, including trees, rocks, fences, posts, lift towers, snow making equipment, snowmobiles and other over-snow vehicles.” “While often referred to as a defense, a release of future liability is [*23] more appropriately characterized as an express assumption of the risk that negates the defendant’s duty of care, an element of the plaintiff’s case.” (Eriksson v. Nunnink (2015) 233 Cal.App.4th 708, 719, 183 Cal. Rptr. 3d 234.) Express assumption of risk agreements are analogous to the implied primary assumption of risk doctrine. (Knight v. Jewett (1992) 3 Cal.4th 296, 308, fn. 4, 11 Cal. Rptr. 2d 2, 834 P.2d 696; Amezcua v. Los Angeles Harley-Davidson, Inc. (2011) 200 Cal.App.4th 217, 227-228, 132 Cal. Rptr. 3d 567.) “‘”The result is that the defendant is relieved of legal duty to the plaintiff; and being under no duty, he cannot be charged with negligence.”‘” (Eriksson, at p. 719, italics omitted.)

Generally, in cases involving an express assumption of risk there is no cause to analyze the activity the complaining party is involved in or the relationship of the parties to that activity. (Allabach v. Santa Clara County Fair Assn., supra, 46 Cal.App.4th at p. 1012; see also Cohen v. Five Brooks Stable (2008) 159 Cal.App.4th 1476, 1484, 72 Cal. Rptr. 3d 471 [“With respect to the question of express waiver, the legal issue is not whether the particular risk of injury appellant suffered is inherent in the recreational activity to which the Release applies [citations], but simply the scope of the Release“]; see also Vine v. Bear Valley Ski Co., supra, 118 Cal.App.4th at p. 590, fn. 2 [“if the express assumption of risk in the release applies, the implied assumption of risk principles . . . would not come into play”].) However, where, as here, plaintiffs allege defendant’s conduct fell outside the scope of the agreement and a more detailed analysis of the scope of a defendant’s duty [*24] is necessary.

“[T]he question of ‘the existence and scope’ of the defendant’s duty is one of law to be decided by the court, not by a jury, and therefore it generally is ‘amenable to resolution by summary judgment.'” (Kahn v. East Side Union High School Dist., supra, 31 Cal.4th at pp. 1003-1004.) A release cannot absolve a party from liability for gross negligence. (City of Santa Barbara v. Superior Court (2007) 41 Cal.4th 747, 750-751, 776-777, 62 Cal. Rptr. 3d 527, 161 P.3d 1095.) In Santa Barbara, our Supreme Court reasoned that “the distinction between ‘ordinary and gross negligence‘ reflects ‘a rule of policy’ that harsher legal consequences should flow when negligence is aggravated instead of merely ordinary.” (Id. at p. 776, quoting Donnelly v. Southern Pacific Co. (1941) 18 Cal.2d 863, 871, 118 P.2d 465.) The issue we must determine here is whether, with all facts and inferences construed in plaintiffs’ favor, Mammoth’s conduct could be found to constitute gross negligence. Plaintiffs alleged in the operative complaint that Mammoth was grossly negligent in the “operation of the subject snow cat,” by operating the tiller on an open run without utilizing spotters and failing to warn skiers of the snowcat’s presence on the run and the danger posed by its tiller. These allegations are insufficient to support a finding of gross negligence.

Ordinary negligence “consists of the failure to exercise the degree of care in a given situation that a reasonable person [*25] under similar circumstances would employ to protect others from harm.” (City of Santa Barbara v. Superior Court, supra, 41 Cal.4th at pp. 753-754.) “‘”[M]ere nonfeasance, such as the failure to discover a dangerous condition or to perform a duty,”‘ amounts to ordinary negligence. [Citation.] However, to support a theory of ‘”[g]ross negligence,”‘ a plaintiff must allege facts showing ‘either a “‘”want of even scant care”‘” or “‘”an extreme departure from the ordinary standard of conduct.”‘” [Citations.]’ [Citations.] ‘”‘[G]ross negligence‘ falls short of a reckless disregard of consequences, and differs from ordinary negligence only in degree, and not in kind. . . .”‘” (Anderson v. Fitness Internat., LLC (2016) 4 Cal.App.5th 867, 881, 208 Cal. Rptr. 3d 792.)

“[T]he nature of a sport is highly relevant in defining the duty of care owed by the particular defendant.” (Knight v. Jewett, supra, 3 Cal.4th at p. 315.) “‘[I]n the sports setting . . . conditions or conduct that otherwise might be viewed as dangerous often are an integral part of the sport itself.’ [Citation.] [Our Supreme Court has] explained that, as a matter of policy, it would not be appropriate to recognize a duty of care when to do so would require that an integral part of the sport be abandoned, or would discourage vigorous participation in sporting events.” (Kahn v. East Side Union High School Dist., supra, 31 Cal.4th at p. 1004.) But the question of duty depends not only on the nature of the sport, but also on the [*26] role of the defendant whose conduct is at issue in a given case. (Ibid.) “‘[A] purveyor of recreational activities owes a duty to a patron not to increase the risks inherent in the activity in which the patron has paid to engage.'” (Id. at p. 1005.) Thus, in cases involving a waiver of liability for future negligence, courts have held that conduct that substantially or unreasonably increased the inherent risk of an activity or actively concealed a known risk could amount to gross negligence, which would not be barred by a release agreement. (See Eriksson v. Nunnink (2011) 191 Cal.App.4th 826, 856, 120 Cal. Rptr. 3d 90.)

Numerous cases have pondered the factual question of whether various ski resorts have increased the inherent risks of skiing or snowboarding. (See Vine v. Bear Valley Ski Co., supra, 118 Cal.App.4th at p. 591 [redesign of snowboarding jump]; Solis v. Kirkwood Resort Co. (2001) 94 Cal.App.4th 354, 366, 114 Cal. Rptr. 2d 265 [construction of the unmarked race start area on the ski run]; Van Dyke v. S.K.I. Ltd. (1998) 67 Cal.App.4th 1310, 1317, 79 Cal. Rptr. 2d 775 [placement of signs in ski run].) It is well established that “‘”‘[e]ach person who participates in the sport of [snow] skiing accepts the dangers that inhere in that sport insofar as the dangers are obvious and necessary. Those dangers include, but are not limited to, injuries which can result from variations in terrain; surface or subsurface snow or ice conditions; bare spots; rocks, trees and other forms of natural [*27] growth or debris; collisions with ski lift towers and their components, with other skiers, or with properly marked or plainly visible snow-making or snow-grooming equipment.'”‘” (Connelly v. Mammoth Mountain Ski Area (1995) 39 Cal.App.4th 8, 12, 45 Cal. Rptr. 2d 855, italics omitted; see also Lackner v. North (2006) 135 Cal.App.4th 1188, 1202, 37 Cal. Rptr. 3d 863; Towns, supra, 147 Cal.App.4th at p. 467.)

Plaintiffs argue the above language is simply dicta and no authority has ever held that colliding with snow-grooming equipment is an inherent risk in snowboarding or skiing. Because there is no authority specifically addressing the inherent risk of snow-grooming equipment, plaintiffs argue, colliding with a snowcat is not an inherent risk of snowboarding. Further, even if it were, Mammoth increased the inherent risk of snowboarding by operating a snowcat and tiller on an open run. We disagree.

The main problem with plaintiffs’ argument that common law has not recognized collisions with snow-grooming equipment as an inherent risk of skiing, is that plaintiffs’ season-pass agreement did. When signing their season-pass agreement, both Willhide-Michiulis and her husband acknowledged that skiing involved the risk of colliding with “over-snow vehicles.” Willhide-Michiulis testified she read the agreement but did not know an “over-snow vehicle” included a snowcat. Plaintiffs, however, [*28] did not argue in the trial court or now on appeal that this term is ambiguous or that the parties did not contemplate collisions with snowcats as a risk of snowboarding. “Over-snow vehicles” is listed in the contract along with “snow making equipment” and “snowmobiles,” indicating a clear intent to include any vehicle used by Mammoth for snow maintenance and snow travel.

Moreover, common law holds that collisions with snow-grooming equipment are an inherent risk of skiing and snowboarding. In Connelly, the plaintiff collided with an unpadded ski lift tower while skiing. (Connelly v. Mammoth Mountain Ski Area, supra, 39 Cal.App.4th at p. 8.) In affirming summary judgment for the defendant, the court found this risk was inherent in the sport and the obvious danger of the tower served as its own warning. (Id. at p. 12.) In concluding that contact with the tower was an inherent risk of the sport, the Connelly court relied on Danieley v. Goldmine Ski Associates, Inc. (1990) 218 Cal.App.3d 111, 266 Cal. Rptr. 749. (Connelly, at p. 12.) In Danieley, a skier collided with a tree. (Danieley, at p. 113.) The Danieley court, in turn, relied on a Michigan statute that set forth certain inherent risks of skiing, including both trees and “‘collisions with ski lift towers and their components'” along with properly marked or plainly visible “‘snow-making or snow-grooming equipment.'” (Id. at p. 123.) “[B]ecause the Michigan [*29] Ski Area Safety Act purports to reflect the preexisting common law, we regard its statutory pronouncements as persuasive authority for what the common law in this subject-matter area should be in California.” (Danieley, at p. 123.)

Although there may not be a published case specifically addressing the inherent risk of snowcats to skiers and snowboarders, a snowcat, otherwise known as snow-grooming equipment, is one of the risks explicitly adopted as California common law by the Danieley and Connelly courts. (Danieley v. Goldmine Ski Associates, Inc., supra, 218 Cal.App.3d at p. 123; Connelly v. Mammoth Mountain Ski Area, supra, 39 Cal.App.4th at p. 12.) Thus, in California, colliding with snow-grooming equipment is an inherent risk of the sport of snowboarding.

Nevertheless, plaintiffs argue operating the tiller of the snowcat on an open snow run increased the inherent risk snowcats pose to snowboarders. We recognize assumption of the risk, either express or implied, applies only to risks that are necessary to the sport. (Souza v. Squaw Valley Ski Corp., supra, 138 Cal.App.4th at pp. 268-269.) In Souza, a child skier collided with a plainly visible aluminum snowmaking hydrant located on a ski run. (Id. at p. 262.) Following Connelly, we affirmed summary judgment for the defendant, finding the snowmaking hydrant was visible and a collision with it was an inherent risk of skiing. (Souza, at pp. 268-272.) The snowmaking equipment in Souza was necessary [*30] and inherent to the sport of skiing because nature had failed to provide adequate snow. (Id. at p. 268.)

Here, plaintiffs claim snowcats operating on open runs are not necessary or inherent to the sport because “[p]recluding a snowcat from operating on an open run would minimize the risks without altering the nature of the sport one whit.” As in Souza, we find the following quote apt: “‘”As is at least implicit in plaintiff’s argument, . . . the doctrine of [primary] assumption of risk . . . would not apply to obvious, known conditions so long as a defendant could feasibly have provided safer conditions. Then, obviously, such risks would not be ‘necessary’ or ‘inherent’. This would effectively emasculate the doctrine, . . . changing the critical inquiry . . . to whether the defendant had a feasible means to remedy [the dangers].”‘” (Souza v. Squaw Valley Ski Corp., supra, 138 Cal.App.4th at p. 269.)

Snow-grooming equipment, including the snowcat and tiller at issue here, are necessary to the sport of snowboarding because the snowcat grooms the snow needed for snowboarding into a skiable surface. Without the tiller also grooming the snow, the snowcat leaves behind an unusable and unsafe surface riddled with berms and holes. This surface is so unsafe that Mammoth’s grooming [*31] guide prohibits snowcat drivers from leaving behind such hazards. Given the purpose of the snowcat and tiller, it cannot be said that they are not inherent and necessary to the sport of snowboarding.

The fact that the snowcat and tiller Willhide-Michiulis collided with was operating during business hours and on an open run does not affect our analysis. Willhide-Michiulis’s husband testified that, although uncommon, he had seen snowcats operating at Mammoth during business hours transporting people. Further, Taylor Lester, a witness to Willhide-Michiulis’s collision and a longtime Mammoth season-pass holder, testified that she had seen snowcats operating at Mammoth on prior occasions as well. Out of the 10 years she has been a season-pass holder, Lester had seen snowcats operating during business hours at Mammoth 20 to 40 times, half of which had been using their tillers.

In fact, Lester testified that it was common for her and her friends, and also her sister and father, to ride close behind snowcats that were tilling so that they could take advantage of the freshly tilled snow the snowcats produced. Freshly-tilled snow is considered desirable and “more fun” because it has not been tarnished [*32] by other skiers. Lester’s sister also testified she liked to “sneak behind” snowcats while they groom runs to ride on the freshly-tilled snow. Even after Willhide-Michiulis’s collision, Lester’s sister still snowboarded behind snowcats to ride the freshly groomed snow.

Given this testimony, we conclude that the use of snowcats and their tillers on ski runs during business hours is inherent to the sport of snowboarding, the use of which does not unreasonably increase the risks associated with the sport. To find Mammoth liable because it operated a snowcat and tiller during business hours would inhibit the vigorous participation in the sport Lester and her sister testified about. Instead of racing to freshly tilled snow to take advantage of its unspoiled status, snowboarders and skiers alike would be prohibited from chasing snowcats and instead have to settle for inferior skiing conditions. Further, snowcats would no longer be used as modes of transportation at ski resorts, a common practice testified to by Willhide-Michiulis’s husband. Or snowcats would operate, but without their tiller, leaving behind unsafe skiing conditions that would doubtlessly interfere with full and vigorous participation [*33] in the sport. (See Kahn v. East Side Union High School Dist., supra, 31 Cal.4th at p. 1004 [“it would not be appropriate to recognize a duty of care when to do so would require that an integral part of the sport be abandoned, or would discourage vigorous participation in sporting events”].)

Regardless of the fact that snowcats and tillers are inherent in the sport of snowboarding, plaintiffs also allege the snowcat Willhide-Michiulis collided with was not obvious and Mammoth was grossly negligent because it failed to provide spotters or warn skiers of the snowcat’s presence on the run or the dangerousness of its tiller. As described, gross negligence requires a showing of “‘either a “‘”want of even scant care”‘” or “‘”an extreme departure from the ordinary standard of conduct.”‘”‘” (Anderson v. Fitness Internat., LLC., supra, 4 Cal.App.5th at p. 881.)

Here, Mammoth did warn plaintiffs of the presence of snowcats and other snow-grooming equipment at the ski resort. At the top and bottom of every chair lift, Mammoth posts signs warning of the presence of snowcats throughout the resort and on snow runs. Mammoth also included these warnings in its trail maps. These warnings were also apparent in plaintiffs’ season-pass agreement, which warned that “the sport involves numerous risks including, but not limited to, the risks [*34] posed by . . . collisions with natural and man-made objects, including . . . snow making equipment, snowmobiles and other over-snow vehicles.” Willhide-Michiulis acknowledged that she saw the warning contained in her season-pass agreement.

Not only were plaintiffs warned about the possible presence of snow-grooming equipment throughout the ski resort, but Willhide-Michiulis was warned of the presence of the specific snowcat she collided with. Before going down the mambo run to fix the pothole on Old Boneyard Road, Mann turned on the safety beacon, warning lights, and audible alarm to the snowcat. This provided warning to all those around the snowcat, whether they could see it or not, to the snowcat’s presence. Further, the snowcat Willhide-Michiulis collided with is large, bright red, and slow-moving, making it generally avoidable by those around it. Indeed, Willhide-Michiulis testified that she saw the snowcat about 150 feet before she collided with it. Although she claims the snowcat cut off her path, the snowcat was traveling less than ten miles an hour before standing nearly motionless while turning onto Old Boneyard Road downhill from Willhide-Michiulis. As the trial court found, [*35] “‘the very existence of a large metal plainly-visible [snowcat] serves as its own warning.'” (Citing Souza v. Squaw Valley Ski Corp., supra, 138 Cal.App.4th at p. 271.) Upon seeing such a warning, it was incumbent upon Willhide-Michiulis to avoid it — nothing was hidden from Willhide-Michiulis’s vision by accident or design.

Given these facts, we cannot conclude, as plaintiffs would have us do, that Mann’s failure to timely signal his turn or Mammoth’s failure to provide spotters or warn of the specific dangers of a tiller constituted gross negligence. Given all the other warnings provided by Mammoth and Mann, plaintiffs cannot show “‘either a “‘”want of even scant care”‘” or “‘”an extreme departure from the ordinary standard of conduct.”‘”‘” (Anderson v. Fitness Internat., LLC., supra, 4 Cal.App.5th at p. 881.) Accordingly, Mammoth was successful in meeting its burden to show the allegations in plaintiffs’ complaint lacked merit.

2

No Triable Issue Of Fact Exists To Preclude Summary Judgment

Because Mammoth met its initial burden, plaintiffs now have the burden to show that a triable issue of fact exists. Plaintiffs argue that one does exist because the way Mann drove the snowcat at the time of the collision was grossly negligent. In addition to the allegations in the complaint — that operating a snowcat and tiller [*36] on an open run was grossly negligent — plaintiffs alleged in their opposition that Mann was grossly negligent also for failing to use a turn signal when making a sharp left turn from the center of a snow run onto an unmarked service road without warning skiers of his presence or the possibility that a snowcat would turn at the locations of Old Boneyard Road. They point to their experts’ declarations and Mann’s violations of Mammoth’s safety standards as support for this contention.

“‘Generally it is a triable issue of fact whether there has been such a lack of care as to constitute gross negligence [citation] but not always.'” (Chavez v. 24 Hour Fitness USA, Inc. (2015) 238 Cal.App.4th 632, 640, 189 Cal. Rptr. 3d 449, quoting Decker v. City of Imperial Beach (1989) 209 Cal.App.3d 349, 358, 257 Cal. Rptr. 356; see also City of Santa Barbara v. Superior Court, supra, 41 Cal.4th at p. 767 [“we emphasize the importance of maintaining a distinction between ordinary and gross negligence, and of granting summary judgment on the basis of that distinction in appropriate circumstances”].) Where the evidence on summary judgment fails to demonstrate a triable issue of material fact, the existence of gross negligence can be resolved as a matter of law. (See Honeycutt v. Meridian Sports Club, LLC (2014) 231 Cal.App.4th 251, 260, 179 Cal. Rptr. 3d 473 [stating a mere difference of opinion regarding how a student should be instructed does not amount to gross negligence]; Frittelli, Inc. v. 350 North Canon Drive, LP (2011) 202 Cal.App.4th 35, 52-53, 135 Cal. Rptr. 3d 761 [no triable issue of material fact precluding summary [*37] judgment, even though the evidence raised conflicting inferences regarding whether measures undertaken by the defendants were effective to mitigate effects on commercial tenant of remodeling project]; Grebing v. 24 Hour Fitness USA, Inc. (2015) 234 Cal.App.4th 631, 639, 184 Cal. Rptr. 3d 155 [no triable issue of material fact where defendant took several measures to ensure that its exercise equipment, on which plaintiff was injured, was well maintained].)”

As described, Mann’s driving of the snowcat with a tiller on an open run was not grossly negligent and was, in fact, an inherent part of the sport of snowboarding and conduct contemplated by the parties in the release of liability agreement. The question now is whether the additional conduct alleged in plaintiffs’ opposition — Mann’s failure to use a turn signal, making of a sharp left turn from the middle of the snow run, failure to warn skiers on mambo of his presence, and failure to warn skiers of the existence of Old Boneyard Road — elevated Mann’s conduct to gross negligence. We conclude it does not.

We have already described why plaintiffs’ claims that Mann failed to provide adequate warning of his existence on the snow run and of his turn did not rise to the level of gross negligence. His additional alleged conduct [*38] of driving down the middle of the snow run and making a sharp left turn onto an unmarked service road also do not justify a finding of gross negligence in light of the precautions taken by both Mammoth and Mann. Mammoth warned plaintiffs of the possible presence of snow-grooming equipment in its season-pass contracts, trail maps, and throughout the ski resort. Mann also turned on the snowcat’s warning lights, beacon, and audible alarm before driving down mambo. Mann testified he constantly looked for skiers and snowboarders while driving the snowcat down mambo and that he checked through the snowcat’s mirrors and windows to make sure he was clear before making the turn onto Old Boneyard Road. He also testified he did not drive the snowcat faster than ten miles an hour while on mambo and was traveling even slower during the turn. This fact was confirmed by Lester. Given these affirmative safety precautions, Mann’s failure to use a turn signal when turning from the middle of the run onto an unmarked service road did not equate to “‘either a “‘”want of even scant care”‘” or “‘”an extreme departure from the ordinary standard of conduct.”‘”‘” (See Anderson v. Fitness Internat., LLC, supra, 4 Cal.App.5th at p. 881.)

Plaintiffs dispute this conclusion by [*39] citing to their expert declarations and Mammoth’s grooming guide as support that Mann’s conduct was an extreme departure from industry standards and Mammoth’s own safety policies. Evidence of conduct that evinces an extreme departure from safety directions or an industry standard could demonstrate gross negligence. (See Jimenez v. 24 Hour Fitness USA, Inc. (2015) 237 Cal.App.4th 546, 561, 188 Cal. Rptr. 3d 228.) Conversely, conduct demonstrating the failure to guard against, or warn of, a dangerous condition typically does not rise to the level of gross negligence. (See DeVito v. State of California (1988) 202 Cal.App.3d 264, 272, 248 Cal. Rptr. 330.)

To illustrate this point, plaintiffs cite two cases. First, they rely on Jimenez. In Jimenez, one of the plaintiffs was injured when she fell backwards off of a moving treadmill and hit her head on an exercise machine that was approximately four feet behind the treadmill. (Jimenez v. 24 Hour Fitness USA, Inc., supra, 237 Cal.App.4th at p. 549.) The plaintiffs presented evidence “indicating a possible industry standard on treadmill safety zones,” including the manufacturer’s statement in its manual that a six-foot space behind the treadmill was necessary for user safety and an expert’s statement that placing other equipment so close to the back of the treadmill greatly increased the risk of injury. (Id. at p. 556.) The court concluded, based on this evidence, a jury could reasonably find [*40] the failure to provide the minimum safety zone was an extreme departure from the ordinary standard of care, and thus a triable issue of fact existed to preclude summary judgment. (Id. at p. 557.)

In Rosencrans v. Dover Images, Ltd. (2011) 192 Cal.App.4th 1072, 122 Cal. Rptr. 3d 22, also relied upon by plaintiffs, the plaintiff was riding a motorcycle when he fell near a platform in an area out of view of other riders at a motocross facility, and was struck by another cyclist. (Id. at pp. 1072, 1077.) The caution flagger, who was supposed to have staffed the platform to alert riders to the presence of fallen cyclists, was not on duty when plaintiff fell. The court found the release plaintiff signed unenforceable against a claim of gross negligence. (Id. at pp. 1077, 1081.) It noted the dangerous nature of the sport, and also found a specific duty on the part of the course operator to provide some form of warning system such as the presence of caution flaggers. (Id. at p. 1084.) Also, the course owner had a safety manual requiring flaggers to stay at their stations whenever riders were on the course, and expert testimony was presented that caution flaggers were required at all such times. (Id. at p. 1086.) Because the evidence could support a finding that the absence of a caution flagger was an extreme and egregious departure from the standard of [*41] care given the applicable safety manual and in light of knowledge of the particular dangers posed, the claim of gross negligence should have survived summary judgment. (Id. at p. 1089.)

Plaintiffs’ reliance on these cases is misplaced for two reasons. First, unlike Jimenez and Rosencrans, plaintiffs presented no expert evidence regarding the safety standards applicable to snowcat drivers. (See Rosencrans v. Dover Images, Ltd., supra, 192 Cal.App.4th at pp. 1086-1087 [triable issue of fact as to gross negligence where a safety expert’s declaration described common safety precautions for motocross and stated that the defendant’s failure to take those safety precautions constituted an extreme departure from the ordinary standard of conduct and showed a blatant disregard for the safety of the participants].) And second, plaintiffs did not produce evidence showing that Mammoth failed to take any safety precautions required by company safety policies.

As described, the trial court did not abuse its discretion in excluding the experts’ declarations from evidence. The declarations did nothing more than to provide conclusions that Mann’s and Mammoth’s conduct violated industry standards and constituted gross negligence. The experts did not articulate what the industry standards [*42] for driving a snowcat or for protecting the skiing public from a snowcat actually were, let alone how Mann and Mammoth violated them. Instead, the experts merely provided their opinions that Mammoth and Mann failed to guard from or warn of the dangerous condition the snowcat and tiller posed. This is insufficient for a showing of gross negligence. (See DeVito v. State of California, supra, 202 Cal.App.3d at p. 272.)

Plaintiffs’ reliance on Mammoth’s grooming guide is likewise misplaced. Plaintiffs characterize the grooming guide as containing “safety standard[s],” which Mann violated by operating the snowcat’s tiller while the public was present. The grooming guide, however, does not purport to be a safety guide or to set safety standards for Mammoth’s snowcat operators. Instead, it is a “manual” where snowcat operators “will find a basis for all training that is a part of the Slope Maintenance Department.” While “all training” may also include safety training, nothing submitted by plaintiffs indicate that the excerpts they rely on are industry or company-wide safety standards as opposed to Mammoth’s guide to “acceptable high quality” grooming.

For example, the grooming guide instructs drivers to “[n]ever operate the tiller when the skiing public is present.” But [*43] the guide also justifies a snowcat’s presence in areas open to the public during emergencies, periods of extremely heavy snow, or for transportation of personnel or materials. Here, there was extremely heavy snow and a hazardous condition requiring Mann to drive a snowcat on public snow runs. The guide further instructs drivers that track marks left behind by a snowcat without a tiller are “not acceptable” and must be removed. It was Mann’s understanding from these guidelines that once a snowcat’s presence was justified in an area open to the public, the tiller also had to be running to leave behind safe skiing conditions.

Further, the guide instructs snowcat drivers to travel on a groomed snow run instead of on ungroomed snow on either side of the run. This is because ungroomed snow is made of unstable soft snow that cannot support the weight of a snowcat. According to the grooming guide, driving on a finished groomed run “is better than risking your cat or your life” on the ungroomed snow on the sides of the run. Thus, Mann did not violate Mammoth’s safety policy by driving down the center of a snow run when traveling to Old Boneyard Road and operating the snowcat’s tiller on a public [*44] run. Because it is not reasonable a jury would find Mann violated safety policies contained in the grooming guide, let alone that that violation constituted more than mere negligence, plaintiffs have not shown that Mann’s or Mammoth’s conduct rose to the level of gross negligence.

II

Venue

Plaintiffs contend the trial court abused its discretion when denying their motion to transfer venue to Los Angeles County where they initially filed their suit. Specifically, plaintiffs argue their motion should have been granted because it was more convenient for the parties and their witnesses to have trial in Los Angeles County and because plaintiffs could not receive a fair trial in Mono County. Thus, plaintiffs argue, “upon reversal of summary judgment, the trial court should be directed to issue an order transferring this action back to Los Angeles.”

As plaintiffs acknowledge, a reversal of the court’s summary judgment order is a vital initial step to reversal of the trial court’s order regarding venue. This is because without first showing that their case is active and trial is pending, plaintiffs cannot show a miscarriage of justice resulting from the denial of their venue motion.

We are enjoined [*45] by our Constitution not to reverse any judgment “for any error as to any matter of procedure, unless, after an examination of the entire cause, including the evidence, the court shall be of the opinion that the error complained of has resulted in a miscarriage of justice.” (Cal. Const., art. VI, § 13; see also Code Civ. Proc., § 475.) Prejudice is not presumed, and “our duty to examine the entire cause arises when and only when the appellant has fulfilled his duty to tender a proper prejudice argument.” (Paterno v. State of California (1999) 74 Cal.App.4th 68, 106, 87 Cal. Rptr. 2d 754.)

Plaintiffs cannot show prejudice resulting from the denial of their venue motion because we upheld the trial court’s summary judgment ruling and their case has been dismissed. Thus, even if the venue motion should have been granted and venue transferred to Los Angeles for trial, there is no trial to be had. Accordingly, we need not address plaintiffs’ claim of error regarding their motion to transfer venue.

DISPOSITION

The judgment is affirmed. Costs are awarded to defendants. (Cal. Rule of Court, rule 8.278, subd. (a)(1).)

Manufacturers Checklist for California Proposition 65

Posted: September 11, 2018 Filed under: California | Tags: Act Lab, California Prop 65, California Proposition 65, Chemical List, Manufacturer, Prop 65, Proposition 65, Warning label Leave a comment-

Determine what chemicals are found in all of your products.

- Look at your SDS (formerly MSDS) sheets. US manufacturers are placing California Prop 65 info on their SDS sheets. It should say whether or not the chemical needs to be listed as a California Prop 65 chemical.

-

If the SDS sheets are not available:

- Contact your manufacturers and get SDS sheets to avoid OSHA issues.

-

Contact your manufactures.

- Confirm that their products do not contain any chemicals on the California Prop 65 list of chemicals: https://oehha.ca.gov/proposition-65/chemicals

-

Get an agreement from them that if their product does contain one of the chemicals on the list or someone states that your product containing their product contains the chemicals they will either:

- Indemnify you

- Take over the litigation or claims and hold your harmless.

- Indemnify you

- Confirm that their products do not contain any chemicals on the California Prop 65 list of chemicals: https://oehha.ca.gov/proposition-65/chemicals

- Contact your manufacturers and get SDS sheets to avoid OSHA issues.

-

If your manufacturer does not know or is not cooperating.

- Find a new manufacturer

-

Send the product to a lab for testing

-

I am recommending Act Labs: https://act-lab.com/

-

Contact

- Devin Walton: 970 443 7825 dwalton@ad-Iab.com

- Michael Baker: (310) 607-0186 ext. 730 mbaker@act-lab.com

- Phil Bash: 562 470 7215 info@act-lab.com

- Devin Walton: 970 443 7825 dwalton@ad-Iab.com

- I get nothing from Act Lab for the referrals. (They promise me they’ll get me a beer at Interbike, but it will be a cheap one probably!)

-

-

You need two things from a testing lab.

- You have to trust them.

- You have to be able to count on them in court if necessary to back up their results.

- You have to trust them.

-

I trust Act Lab. They know what they are doing, and they enjoy standing behind their results.

- They have testing facilities in the US and China.

- They have testing facilities in the US and China.

-

- Find a new manufacturer

- Look at your SDS (formerly MSDS) sheets. US manufacturers are placing California Prop 65 info on their SDS sheets. It should say whether or not the chemical needs to be listed as a California Prop 65 chemical.

-

Based on your findings

-

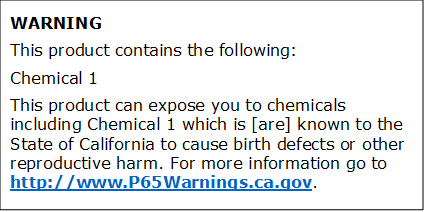

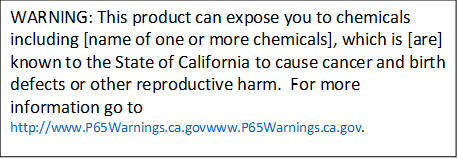

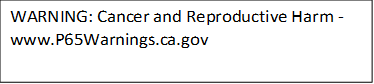

If you have chemicals in some products create the warning label for one of the chemicals found and place it on the product where the consumer can see the label before purchasing.

- Place the warning label on your website

- Place the warning label in your catalog

-

Notify all retailers, in and out of California, of the products that must have a warning label on them.

- Supply the warning label to those retailers in California carrying products requiring the warning.

- Supply the warning label to those retailers in California carrying products requiring the warning.

- Place the warning label on your website

-

If your product does not require a warning label.

- Have a beer.

- Have a beer.

-

-

When does California Prop 65 not apply.

- If your company has ten of few employees, you do not have to post warnings on the products, however, I still would, see below.

- If your products containing the chemicals on the list were manufactured prior to August 30, 2018 you do not have to place the warning label on the product, but I still would, see below.

- If your company has ten of few employees, you do not have to post warnings on the products, however, I still would, see below.

-

Why CYA if you don’t have to.

-

The cost of proving you don’t qualify is going to exceed the cost of complying.

-

Attorneys and consumers cannot read UPC codes to determine the date of a manufacture.

- The cost to you of proving the manufacturing date is going to take time to show how the UPC code shows the manufacturing date. You may also have to supply additional documentation to support this information.

- The cost to you of proving the manufacturing date is going to take time to show how the UPC code shows the manufacturing date. You may also have to supply additional documentation to support this information.

-

Attorneys and consumers do not know how many employees you have.

- Unless you want to send copies of your payroll to law firms proving that you have less than ten employees is nearly impossible.

- Unless you want to send copies of your payroll to law firms proving that you have less than ten employees is nearly impossible.

-

- The cost of proving you do not need the warning label on your product is much greater than the cost of just placing the warning label on the product.

-

-

Is the warning label going to stop sales?

-

California Consumers will not care about the warning label; it is going to be on everything they buy.

-

Non-California consumers are going to get used to seeing it eventually, and they won’t care.