New Wilderness Medical Society (WMS) guidelines for Care of Burns in the Wilderness

Posted: November 10, 2025 Filed under: First Aid, Medical | Tags: burn, firstaid, medical-standard, Wilderness First Aid, Wilderness Medical Society Leave a commentWilderness Medical Society Clinical Practice Guideline on Care of Burns in the Wilderness (You may need to be a member to subscribe.)

New Burn Care are guidelines for wilderness care, meaning this is the new standard in wilderness burn care:

Standards are a confusing issue in outdoor recreation. Standards can be created by your own organization, which only apply to you, but third parties think they are protecting you (rarely successful), and by how the world works. Standards are the lowest acceptable level of doing or not doing something as seen or reviewed by a reasonable person.

That means that a standard is the lowest level of acceptable doing something (or not doing something).

A standard is how you are going to be measured in the courtroom. Did you operate or perform at the level of the standard? If you did not, you are probably going to be found negligent, absent a defense, and writing a check.

Medical standards are nonexistent. Physicians are smart enough to know that creating a standard creates lawsuits. Creating standards also limits creativity. Being creative, not following the standard, can guarantee a lawsuit if someone is injured, so why be creative? Physicians do create guidelines. It gives other physicians and, in this case, first aid providers the best knowledge available at the time, knowing that not everyone may be able to meet the guidelines, and care is going to change, improve, and hopefully get better.

That is why you always need to be aware of any new standard, no matter who or how it was created. You may be held to that standard. In this case, because the New Wilderness Medical Society (WMS) knows what it is doing, they have not created a standard but a guideline. If you don’t follow the advice provided in the guideline, you have not breached the standard of care.

You can use this information to fight claims that you violated a standard, arguing that a group of physicians who specialize in the first aid in the wilderness have this guideline. Since the guideline was made by physicians, after months or even years of research, you were not negligent when you did not follow the “standard” created by another group.

These current burn guidelines have not changed much in how we practice burn treatments; they have just been put together for first aid providers in wilderness settings.

One thing you should always be aware of, how the words used in a guideline are defined. Wilderness, as defined by the New Wilderness Medical Society, may have a different definition from how the US Forest Service or the rest of the federal government defines wilderness. You can find the New Wilderness Medical Society definition of wilderness here: The Definition of Wilderness Medicine & Wilderness EMS.

You can find most of the New Wilderness Medical Society guidelines in Wilderness Medical Society Practice Guidelines for Wilderness Emergency Care; however, several guidelines have been created and updated since this book was published in 2006.

To stay up to date, to see research leading to new first aid guidelines, and to be able to read and stay current on all of the guidelines, you need to become a member of the Wilderness Medical Society (WMS).

Why Is This Interesting?

Because if you are providing first aid outside of the community, cities, towns, or the EMS area of operation, this will be one of the criteria used to judge how well you did.

Be prepared to defend what you did using the guidelines based on how your situation varied from the criteria the guidelines were developed for, if necessary.

First of all, take care of someone burned, wherever you find them.

To read more articles on Standards and Guidelines, see:

So, if you write standards, you can then use them to make money when someone sues your competitors.

Trade Association Standards sink a Summer Camp when the plaintiff uses them to prove the Camp was negligent

ACA Standards are used by the Expert for the Plaintiff in a lawsuit against a Camp

Plaintiff uses standards of ACCT to cost defendant $4.7 million

So, if you write standards, you can then use them to make money when someone sues your competitors.

@RecreationLaw #RecLaw #RecreationLaw #OutdoorRecreationLaw #OutdoorLaw #OutdoorIndustry

Jim Moss

I represent Manufacturers, Outfitters, Guides, Reps, Colleges & Universities, Camps, Youth Programs, Adventure Programs, and Businesses.

My CV

What do you think? Leave a comment below.

If you like this, let your friends know or post it on FB, Twitter or LinkedIn

Author: Outdoor Recreation Insurance, Risk Management, and Law To Purchase, Go Here

Facebook Page: Outdoor Recreation & Adventure Travel Law

Email: Jim@Rec-Law.US Recreation Law Rec-law@recreation-law.com James H. Moss

Jim is the author or co-author of six books about the legal issues in the outdoor recreation world; the latest is Outdoor Recreation Insurance, Risk Management and Law.

To see Jim’s complete bio, go here, and to see his CV, you can find it here. To find out the purpose of this website, go here.

Copyright 2025 Recreation Law (720) 334 8529

G-YQ06K3L262

@2025 Summit Magic Publishing, LLC

Do Releases Work? Should I be using a Release in my Business? Will my customers be upset if I make them sign a release?

Posted: May 18, 2021 Filed under: Activity / Sport / Recreation, Adventure Travel, Assumption of the Risk, Avalanche, Camping, Challenge or Ropes Course, Climbing, Climbing Wall, Contract, Cycling, Equine Activities (Horses, Donkeys, Mules) & Animals, First Aid, Health Club, Indoor Recreation Center, Insurance, Jurisdiction and Venue (Forum Selection), Medical, Minors, Youth, Children, Mountain Biking, Mountaineering, Paddlesports, Playground, Racing, Racing, Release (pre-injury contract not to sue), Risk Management, Rivers and Waterways, Rock Climbing, Scuba Diving, Sea Kayaking, Search and Rescue (SAR), Ski Area, Skier v. Skier, Skiing / Snow Boarding, Skydiving, Paragliding, Hang gliding, Snow Tubing, Sports, Summer Camp, Swimming, Triathlon, Whitewater Rafting, Youth Camps, Zip Line | Tags: #ORLawTextbook, #ORRiskManagment, #OutdoorRecreationRiskManagementInsurance&Law, #OutdoorRecreationTextbook, @SagamorePub, Accidents, Angry Guest, Dealing with Claims, General Liability Insurance, Guide, http://www.rec-law.us/ORLawTextbook, Injured Guest, Insurance policy, James H. Moss J.D., Jim Moss, Liability insurance, OR Textbook, Outdoor Recreation Insurance, Outdoor Recreation Law, Outdoor Recreation Risk Management, Outfitter, RecreationLaw, Risk Management, risk management plan, Textbook, Understanding, Understanding Insurance, Understanding Risk Management, Upset Guest Leave a comment These and many other questions are answered in my book Outdoor Recreation Risk Management, Insurance and Law.

These and many other questions are answered in my book Outdoor Recreation Risk Management, Insurance and Law.

Releases, (or as some people incorrectly call them waivers) are a legal agreement that in advance of any possible injury identifies who will pay for what. Releases can and to stop lawsuits.

This book will explain releases and other defenses you can use to put yourself in a position to stop lawsuits and claims.

This book can help you understand why people sue and how you can and should deal with injured, angry or upset guests of your business.

This book is designed to help you rest easy about what you need to do and  how to do it. More importantly, this book will make sure you keep your business afloat and moving forward.

how to do it. More importantly, this book will make sure you keep your business afloat and moving forward.

You did not get into the outdoor recreation business to worry or spend nights staying awake. Get prepared and learn how and why so you can sleep and quit worrying.

Table of Contents

Chapter 1 Outdoor Recreation Risk Management, Law, and Insurance: An Overview

Chapter 2 U.S. Legal System and Legal Research

Chapter 3 Risk 25

Chapter 4 Risk, Accidents, and Litigation: Why People Sue

Chapter 5 Law 57

Chapter 6 Statutes that Affect Outdoor Recreation

Chapter 7 Pre-injury Contracts to Prevent Litigation: Releases

Chapter 8 Defenses to Claims

Chapter 9 Minors

Chapter 10 Skiing and Ski Areas

Chapter 11 Other Commercial Recreational Activities

Chapter 12 Water Sports, Paddlesports, and water-based activities

Chapter 13 Rental Programs

Chapter 14 Insurance

$130.00 plus shipping

Artwork by Don Long donaldoelong@earthlink.net

New Book Aids Both CEOs and Students

Posted: August 1, 2019 Filed under: Adventure Travel, Assumption of the Risk, Camping, Challenge or Ropes Course, Climbing, Climbing Wall, Contract, Cycling, Equine Activities (Horses, Donkeys, Mules) & Animals, First Aid, Insurance, Jurisdiction and Venue (Forum Selection), Legal Case, Medical, Mountain Biking, Mountaineering, Paddlesports, Release (pre-injury contract not to sue), Risk Management, Rivers and Waterways, Rock Climbing, Sea Kayaking, Ski Area, Skiing / Snow Boarding, Skydiving, Paragliding, Hang gliding, Swimming, Whitewater Rafting, Zip Line | Tags: Adventure travel, and Law, assumption of the risk, camping, Case Analysis, Challenge or Ropes Course, Climbing, Climbing Wall, Contract, Cycling, Desk Reference, Donkeys, Equine Activities (Horses, first aid, Good Samaritan Statutes, Hang gliding, Insurance, James H. Moss, Jurisdiction and Venue (Forum Selection), Law, Legal Case, Medical, Mountain biking, Mountaineering, Mules) & Animals, Negligence, Outdoor Industry, Outdoor recreation, Outdoor Recreation Insurance, Outdoor Recreation Risk Management, Paddlesports, Paragliding, Recreational Use Statute, Reference Book, Release (pre-injury contract not to sue), Reward, Risk, Risk Management, Rivers and Waterways, Rock climbing, Sea Kayaking, ski area, Ski Area Statutes, Skiing / Snow Boarding, Skydiving, swimming, Textbook, Whitewater Rafting, zip line Leave a comment“Outdoor Recreation Insurance, Risk Management, and Law” is a definitive guide to preventing and overcoming legal issues in the outdoor recreation industry

Outdoor Recreation Insurance, Risk Management, and Law

Denver based James H. Moss, JD, an attorney who specializes in the legal issues of outdoor recreation and adventure travel companies, guides, outfitters, and manufacturers, has written a comprehensive legal guidebook titled, “Outdoor Recreation Insurance, Risk Management, and Law”. Sagamore Publishing, a well-known Illinois-based educational publisher, distributes the book.

Mr. Moss, who applied his 30 years of experience with the legal, insurance, and risk management issues of the outdoor industry, wrote the book in order to fill a void.

“There was nothing out there that looked at case law and applied it to legal problems in outdoor recreation,” Moss explained. “The goal of this book is to provide sound advice based on past law and experience.”

The Reference book is sold via the Summit Magic Publishing, LLC.

While written as a college-level textbook, the guide also serves as a legal primer for executives, managers, and business owners in the field of outdoor recreation. It discusses how to tackle, prevent, and overcome legal issues in all areas of the industry.

The book is organized into 14 chapters that are easily accessed as standalone topics, or read through comprehensively. Specific topics include rental programs, statues that affect outdoor recreation, skiing and ski areas, and defenses to claims. Mr. Moss also incorporated listings of legal definitions, cases, and statutes, making the book easy for laypeople to understand.

PURCHASE

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Table of Cases

Introduction

Outdoor Recreation Law and Insurance: Overview

Risk

Risk

Perception versus Actual Risk

Risk v. Reward

Risk Evaluation

Risk Management Strategies

Humans & Risk

Risk = Accidents

Accidents may/may not lead to litigation

How Do You Deal with Risk?

How Does Acceptance of Risk Convert to Litigation?

Negative Feelings against the Business

Risk, Accidents & Litigation

No Real Acceptance of the Risk

No Money to Pay Injury Bills

No Health Insurance

Insurance Company Subrogation

Negative Feelings

Litigation

Dealing with Different People

Dealing with Victims

Develop a Friend & Eliminate a Lawsuit

Don’t Compound Minor Problems into Major Lawsuits

Emergency Medical Services

Additional Causes of Lawsuits in Outdoor Recreation

Employees

How Do You Handle A Victim?

Dealing with Different People

Dealing with Victims

Legal System in the United States

Courts

State Court System

Federal Court System

Other Court Systems

Laws

Statutes

Parties to a Lawsuit

Attorneys

Trials

Law

Torts

Negligence

Duty

Breach of the Duty

Injury

Proximate Causation

Damages

Determination of Duty Owed

Duty of an Outfitter

Duty of a Guide

Duty of Livery Owner

Duty of Rental Agent

Duty of Volunteer Youth Leader

In Loco Parentis

Intentional Torts

Gross Negligence

Willful & Wanton Negligence

Intentional Negligence

Negligence Per Se

Strict Liability

Attractive Nuisance

Results of Acts That Are More than Ordinary Negligence

Product Liability

Contracts

Breach of Contract

Breach of Warranty

Express Warranty

Implied Warranty

Warranty of Fitness for a Particular Purpose

Warranty of Merchantability

Warranty of Statute

Detrimental Reliance

Unjust Enrichment

Liquor Liability

Food Service Liability

Damages

Compensatory Damages

Special Damages

Punitive Damages

Statutory Defenses

Skier Safety Acts

Whitewater Guides & Outfitters

Equine Liability Acts

Legal Defenses

Assumption of Risk

Express Assumption of Risk

Implied Assumption of Risk

Primary Assumption of Risk

Secondary Assumption of Risk

Contributory Negligence

Assumption of Risk & Minors

Inherent Dangers

Assumption of Risk Documents.

Assumption of Risk as a Defense.

Statutory Assumption of Risk

Express Assumption of Risk

Contributory Negligence

Joint and Several Liability

Release, Waivers & Contracts Not to Sue

Why do you need them

Exculpatory Agreements

Releases

Waivers

Covenants Not to sue

Who should be covered

What should be included

Negligence Clause

Jurisdiction & Venue Clause

Assumption of Risk

Other Clauses

Indemnification

Hold Harmless Agreement

Liquidated Damages

Previous Experience

Misc

Photography release

Video Disclaimer

Drug and/or Alcohol clause

Medical Transportation & Release

HIPAA

Problem Areas

What the Courts do not want to see

Statute of Limitations

Minors

Adults

Defenses Myths

Agreements to Participate

Parental Consent Agreements

Informed Consent Agreements

Certification

Accreditation

Standards, Guidelines & Protocols

License

Specific Occupational Risks

Personal Liability of Instructors, Teachers & Educators

College & University Issues

Animal Operations, Packers

Equine Activities

Canoe Livery Operations

Tube rentals

Downhill Skiing

Ski Rental Programs

Indoor Climbing Walls

Instructional Programs

Mountaineering

Retail Rental Programs

Rock Climbing

Tubing Hills

Whitewater Rafting

Risk Management Plan

Introduction for Risk Management Plans

What Is A Risk Management Plan?

What should be in a Risk Management Plan

Risk Management Plan Template

Ideas on Developing a Risk Management Plan

Preparing your Business for Unknown Disasters

Building Fire & Evacuation

Dealing with an Emergency

Insurance

Theory of Insurance

Insurance Companies

Deductibles

Self-Insured Retention

Personal v. Commercial Policies

Types of Policies

Automobile

Comprehension

Collision

Bodily Injury

Property Damage

Uninsured Motorist

Personal Injury Protection

Non-Owned Automobile

Hired Car

Fire Policy

Coverage

Liability

Named Peril v. All Risk

Commercial Policies

Underwriting

Exclusions

Special Endorsements

Rescue Reimbursement

Policy Procedures

Coverage’s

Agents

Brokers

General Agents

Captive Agents

Types of Policies

Claims Made

Occurrence

Claims

Federal and State Government Insurance Requirements

Bibliography

Index

The 427-page volume is sold via Summit Magic Publishing, LLC.

What is a Risk Management Plan and What do You Need in Yours?

Posted: July 25, 2019 Filed under: Activity / Sport / Recreation, Adventure Travel, Assumption of the Risk, Avalanche, Camping, Challenge or Ropes Course, Climbing, Climbing Wall, Contract, Cycling, Equine Activities (Horses, Donkeys, Mules) & Animals, First Aid, Health Club, Indoor Recreation Center, Jurisdiction and Venue (Forum Selection), Legal Case, Medical, Minors, Youth, Children, Mountain Biking, Mountaineering, Paddlesports, Playground, Racing, Racing, Release (pre-injury contract not to sue), Risk Management, Rivers and Waterways, Rock Climbing, Scuba Diving, Sea Kayaking, Search and Rescue (SAR), Ski Area, Skier v. Skier, Skiing / Snow Boarding, Skydiving, Paragliding, Hang gliding, Snow Tubing, Sports, Summer Camp, Swimming, Triathlon, Whitewater Rafting, Youth Camps, Zip Line | Tags: #ORLawTextbook, #ORRiskManagment, #OutdoorRecreationRiskManagementInsurance&Law, #OutdoorRecreationTextbook, @SagamorePub, Adventure travel, and Law, assumption of the risk, camping, Case Analysis, Challenge or Ropes Course, Climbing, Climbing Wall, Contract, Cycling, Donkeys, Equine Activities (Horses, first aid, General Liability Insurance, Good Samaritan Statutes, Guide, Hang gliding, http://www.rec-law.us/ORLawTextbook, Insurance, Insurance policy, James H. Moss, James H. Moss J.D., Jim Moss, Jurisdiction and Venue (Forum Selection), Legal Case, Liability insurance, Medical, Mountain biking, Mountaineering, Mules) & Animals, Negligence, OR Textbook, Outdoor Recreation Insurance, Outdoor Recreation Law, Outdoor Recreation Risk Management, Outfitter, Paddlesports, Paragliding, Recreational Use Statute, Release (pre-injury contract not to sue), Risk Management, risk management plan, Rivers and Waterways, Rock climbing, Sea Kayaking, ski area, Ski Area Statutes, Skiing / Snow Boarding, Skydiving, swimming, Textbook, Understanding, Understanding Insurance, Understanding Risk Management, Whitewater Rafting, zip line Leave a commentEveryone has told you, that you need a risk management plan. A plan to follow if you have

Outdoor Recreation Insurance, Risk Management, and Law

a crisis. You‘ve seen several and they look burdensome and difficult to write. Need help writing a risk management plan? Need to know what should be in your risk management plan? Need Help?

This book can help you understand and write your plan. This book is designed to help you rest easy about what you need to do and how to do it. More importantly, this book will make sure your plan is a workable plan, not one that will create liability for you.

Table of Contents

Chapter 1 Outdoor Recreation Risk Management, Law, and Insurance: An Overview

Chapter 2 U.S. Legal System and Legal Research

Chapter 3 Risk 25

Chapter 4 Risk, Accidents, and Litigation: Why People Sue

Chapter 5 Law 57

Chapter 6 Statutes that Affect Outdoor Recreation

Chapter 7 PreInjury Contracts to Prevent Litigation: Releases

Chapter 8 Defenses to Claims

Chapter 9 Minors

Chapter 10 Skiing and Ski Areas

Chapter 11 Other Commercial Recreational Activities

Chapter 12 Water Sports, Paddlesports, and water-based activities

Chapter 13 Rental Programs

Chapter 14 Insurance

$130.00 plus shipping

Can’t Sleep? Guest was injured, and you don’t know what to do? This book can answer those questions for you.

Posted: July 23, 2019 Filed under: Adventure Travel, Assumption of the Risk, Avalanche, Camping, Climbing, Climbing Wall, Contract, Criminal Liability, Cycling, Equine Activities (Horses, Donkeys, Mules) & Animals, First Aid, Health Club, How, Indoor Recreation Center, Insurance, Jurisdiction and Venue (Forum Selection), Medical, Minors, Youth, Children, Mountain Biking, Mountaineering, Paddlesports, Playground, Racing, Racing, Release (pre-injury contract not to sue), Risk Management, Rivers and Waterways, Rock Climbing, Scuba Diving, Sea Kayaking, Search and Rescue (SAR), Ski Area, Skier v. Skier, Skiing / Snow Boarding, Skydiving, Paragliding, Hang gliding, Snow Tubing, Sports, Summer Camp, Swimming, Triathlon, Whitewater Rafting, Youth Camps, Zip Line | Tags: #ORLawTextbook, #ORRiskManagment, #OutdoorRecreationRiskManagementInsurance&Law, #OutdoorRecreationTextbook, @SagamorePub, Accidents, Angry Guest, Dealing with Claims, General Liability Insurance, Guide, http://www.rec-law.us/ORLawTextbook, Injured Guest, Insurance policy, James H. Moss J.D., Jim Moss, Liability insurance, OR Textbook, Outdoor Recreation Insurance, Outdoor Recreation Law, Outdoor Recreation Risk Management, Outfitter, RecreationLaw, Risk Management, risk management plan, Textbook, Understanding, Understanding Insurance, Understanding Risk Management, Upset Guest Leave a comment An injured guest is everyone’s business owner’s nightmare. What happened, how do you make sure it does not happen again, what can you do to help the guest, can you help the guests are just some of the questions that might be keeping you up at night.

An injured guest is everyone’s business owner’s nightmare. What happened, how do you make sure it does not happen again, what can you do to help the guest, can you help the guests are just some of the questions that might be keeping you up at night.

This book can help you understand why people sue and how you can and should deal with injured, angry or upset guests of your business.

This book is designed to help you rest easy about what you need to do and how to do it. More importantly, this book will make sure you keep your business afloat and moving forward.

You did not get into the outdoor recreation business to worry or spend nights staying awake. Get prepared and learn how and why so you can sleep and quit worrying.

Table of Contents

Chapter 1 Outdoor Recreation Risk Management, Law, and Insurance: An Overview

Chapter 2 U.S. Legal System and Legal Research

Chapter 3 Risk 25

Chapter 4 Risk, Accidents, and Litigation: Why People Sue

Chapter 5 Law 57

Chapter 6 Statutes that Affect Outdoor Recreation

Chapter 7 Pre-injury Contracts to Prevent Litigation: Releases

Chapter 8 Defenses to Claims

Chapter 9 Minors

Chapter 10 Skiing and Ski Areas

Chapter 11 Other Commercial Recreational Activities

Chapter 12 Water Sports, Paddlesports, and water-based activities

Chapter 13 Rental Programs

Chapter 14 Insurance

$130.00 plus shipping

Do Releases Work? Should I be using a Release in my Business? Will my customers be upset if I make them sign a release?

Posted: April 30, 2019 Filed under: Activity / Sport / Recreation, Adventure Travel, Assumption of the Risk, Avalanche, Camping, Challenge or Ropes Course, Climbing, Climbing Wall, Contract, Cycling, Equine Activities (Horses, Donkeys, Mules) & Animals, First Aid, Health Club, Indoor Recreation Center, Insurance, Jurisdiction and Venue (Forum Selection), Medical, Minors, Youth, Children, Mountain Biking, Mountaineering, Paddlesports, Playground, Racing, Racing, Release (pre-injury contract not to sue), Risk Management, Rivers and Waterways, Rock Climbing, Scuba Diving, Sea Kayaking, Search and Rescue (SAR), Ski Area, Skier v. Skier, Skiing / Snow Boarding, Skydiving, Paragliding, Hang gliding, Snow Tubing, Sports, Summer Camp, Swimming, Triathlon, Whitewater Rafting, Youth Camps, Zip Line | Tags: #ORLawTextbook, #ORRiskManagment, #OutdoorRecreationRiskManagementInsurance&Law, #OutdoorRecreationTextbook, @SagamorePub, Accidents, Angry Guest, Dealing with Claims, General Liability Insurance, Guide, http://www.rec-law.us/ORLawTextbook, Injured Guest, Insurance policy, James H. Moss J.D., Jim Moss, Liability insurance, OR Textbook, Outdoor Recreation Insurance, Outdoor Recreation Law, Outdoor Recreation Risk Management, Outfitter, RecreationLaw, Risk Management, risk management plan, Textbook, Understanding, Understanding Insurance, Understanding Risk Management, Upset Guest Leave a comment These and many other questions are answered in my book Outdoor Recreation Risk Management, Insurance and Law.

These and many other questions are answered in my book Outdoor Recreation Risk Management, Insurance and Law.

Releases, (or as some people incorrectly call them waivers) are a legal agreement that in advance of any possible injury identifies who will pay for what. Releases can and to stop lawsuits.

This book will explain releases and other defenses you can use to put yourself in a position to stop lawsuits and claims.

This book can help you understand why people sue and how you can and should deal with injured, angry or upset guests of your business.

This book is designed to help you rest easy about what you need to do and  how to do it. More importantly, this book will make sure you keep your business afloat and moving forward.

how to do it. More importantly, this book will make sure you keep your business afloat and moving forward.

You did not get into the outdoor recreation business to worry or spend nights staying awake. Get prepared and learn how and why so you can sleep and quit worrying.

Table of Contents

Chapter 1 Outdoor Recreation Risk Management, Law, and Insurance: An Overview

Chapter 2 U.S. Legal System and Legal Research

Chapter 3 Risk 25

Chapter 4 Risk, Accidents, and Litigation: Why People Sue

Chapter 5 Law 57

Chapter 6 Statutes that Affect Outdoor Recreation

Chapter 7 Pre-injury Contracts to Prevent Litigation: Releases

Chapter 8 Defenses to Claims

Chapter 9 Minors

Chapter 10 Skiing and Ski Areas

Chapter 11 Other Commercial Recreational Activities

Chapter 12 Water Sports, Paddlesports, and water-based activities

Chapter 13 Rental Programs

Chapter 14 Insurance

$99.00 plus shipping

Artwork by Don Long donaldoelong@earthlink.net

Can’t Sleep? Guest was injured, and you don’t know what to do? This book can answer those questions for you.

Posted: April 16, 2019 Filed under: Adventure Travel, Assumption of the Risk, Avalanche, Camping, Climbing, Climbing Wall, Contract, Criminal Liability, Cycling, Equine Activities (Horses, Donkeys, Mules) & Animals, First Aid, Health Club, How, Indoor Recreation Center, Insurance, Jurisdiction and Venue (Forum Selection), Medical, Minors, Youth, Children, Mountain Biking, Mountaineering, Paddlesports, Playground, Racing, Racing, Release (pre-injury contract not to sue), Risk Management, Rivers and Waterways, Rock Climbing, Scuba Diving, Sea Kayaking, Search and Rescue (SAR), Ski Area, Skier v. Skier, Skiing / Snow Boarding, Skydiving, Paragliding, Hang gliding, Snow Tubing, Sports, Summer Camp, Swimming, Triathlon, Whitewater Rafting, Youth Camps, Zip Line | Tags: #ORLawTextbook, #ORRiskManagment, #OutdoorRecreationRiskManagementInsurance&Law, #OutdoorRecreationTextbook, @SagamorePub, Accidents, Angry Guest, Dealing with Claims, General Liability Insurance, Guide, http://www.rec-law.us/ORLawTextbook, Injured Guest, Insurance policy, James H. Moss J.D., Jim Moss, Liability insurance, OR Textbook, Outdoor Recreation Insurance, Outdoor Recreation Law, Outdoor Recreation Risk Management, Outfitter, RecreationLaw, Risk Management, risk management plan, Textbook, Understanding, Understanding Insurance, Understanding Risk Management, Upset Guest Leave a comment An injured guest is everyone’s business owner’s nightmare. What happened, how do you make sure it does not happen again, what can you do to help the guest, can you help the guests are just some of the questions that might be keeping you up at night.

An injured guest is everyone’s business owner’s nightmare. What happened, how do you make sure it does not happen again, what can you do to help the guest, can you help the guests are just some of the questions that might be keeping you up at night.

This book can help you understand why people sue and how you can and should deal with injured, angry or upset guests of your business.

This book is designed to help you rest easy about what you need to do and how to do it. More importantly, this book will make sure you keep your business afloat and moving forward.

You did not get into the outdoor recreation business to worry or spend nights staying awake. Get prepared and learn how and why so you can sleep and quit worrying.

Table of Contents

Chapter 1 Outdoor Recreation Risk Management, Law, and Insurance: An Overview

Chapter 2 U.S. Legal System and Legal Research

Chapter 3 Risk 25

Chapter 4 Risk, Accidents, and Litigation: Why People Sue

Chapter 5 Law 57

Chapter 6 Statutes that Affect Outdoor Recreation

Chapter 7 Pre-injury Contracts to Prevent Litigation: Releases

Chapter 8 Defenses to Claims

Chapter 9 Minors

Chapter 10 Skiing and Ski Areas

Chapter 11 Other Commercial Recreational Activities

Chapter 12 Water Sports, Paddlesports, and water-based activities

Chapter 13 Rental Programs

Chapter 14 Insurance

$130.00 plus shipping

What is a Risk Management Plan and What do You Need in Yours?

Posted: April 11, 2019 Filed under: Activity / Sport / Recreation, Adventure Travel, Assumption of the Risk, Avalanche, Camping, Challenge or Ropes Course, Climbing, Climbing Wall, Contract, Cycling, Equine Activities (Horses, Donkeys, Mules) & Animals, First Aid, Health Club, Indoor Recreation Center, Jurisdiction and Venue (Forum Selection), Legal Case, Medical, Minors, Youth, Children, Mountain Biking, Mountaineering, Paddlesports, Playground, Racing, Racing, Release (pre-injury contract not to sue), Risk Management, Rivers and Waterways, Rock Climbing, Scuba Diving, Sea Kayaking, Search and Rescue (SAR), Ski Area, Skier v. Skier, Skiing / Snow Boarding, Skydiving, Paragliding, Hang gliding, Snow Tubing, Sports, Summer Camp, Swimming, Triathlon, Whitewater Rafting, Youth Camps, Zip Line | Tags: #ORLawTextbook, #ORRiskManagment, #OutdoorRecreationRiskManagementInsurance&Law, #OutdoorRecreationTextbook, @SagamorePub, Adventure travel, and Law, assumption of the risk, camping, Case Analysis, Challenge or Ropes Course, Climbing, Climbing Wall, Contract, Cycling, Donkeys, Equine Activities (Horses, first aid, General Liability Insurance, Good Samaritan Statutes, Guide, Hang gliding, http://www.rec-law.us/ORLawTextbook, Insurance, Insurance policy, James H. Moss, James H. Moss J.D., Jim Moss, Jurisdiction and Venue (Forum Selection), Legal Case, Liability insurance, Medical, Mountain biking, Mountaineering, Mules) & Animals, Negligence, OR Textbook, Outdoor Recreation Insurance, Outdoor Recreation Law, Outdoor Recreation Risk Management, Outfitter, Paddlesports, Paragliding, Recreational Use Statute, Release (pre-injury contract not to sue), Risk Management, risk management plan, Rivers and Waterways, Rock climbing, Sea Kayaking, ski area, Ski Area Statutes, Skiing / Snow Boarding, Skydiving, swimming, Textbook, Understanding, Understanding Insurance, Understanding Risk Management, Whitewater Rafting, zip line Leave a commentEveryone has told you, you need a risk management plan. A plan to follow if you have  a crisis. You‘ve seen several and they look burdensome and difficult to write. Need help writing a risk management plan? Need to know what should be in your risk management plan? Need Help?

a crisis. You‘ve seen several and they look burdensome and difficult to write. Need help writing a risk management plan? Need to know what should be in your risk management plan? Need Help?

This book can help you understand and write your plan. This book is designed to help you rest easy about what you need to do and how to do it. More importantly, this book will make sure you plan is a workable plan, not one that will create liability for you.

Table of Contents

Chapter 1 Outdoor Recreation Risk Management, Law, and Insurance: An Overview

Chapter 2 U.S. Legal System and Legal Research

Chapter 3 Risk 25

Chapter 4 Risk, Accidents, and Litigation: Why People Sue

Chapter 5 Law 57

Chapter 6 Statutes that Affect Outdoor Recreation

Chapter 7 PreInjury Contracts to Prevent Litigation: Releases

Chapter 8 Defenses to Claims

Chapter 9 Minors

Chapter 10 Skiing and Ski Areas

Chapter 11 Other Commercial Recreational Activities

Chapter 12 Water Sports, Paddlesports, and water-based activities

Chapter 13 Rental Programs

Chapter 14 Insurance

$99.00 plus shipping

Ever Wonder what an EMT is Legally allowed to do versus a EMT-IV or Paramedic?

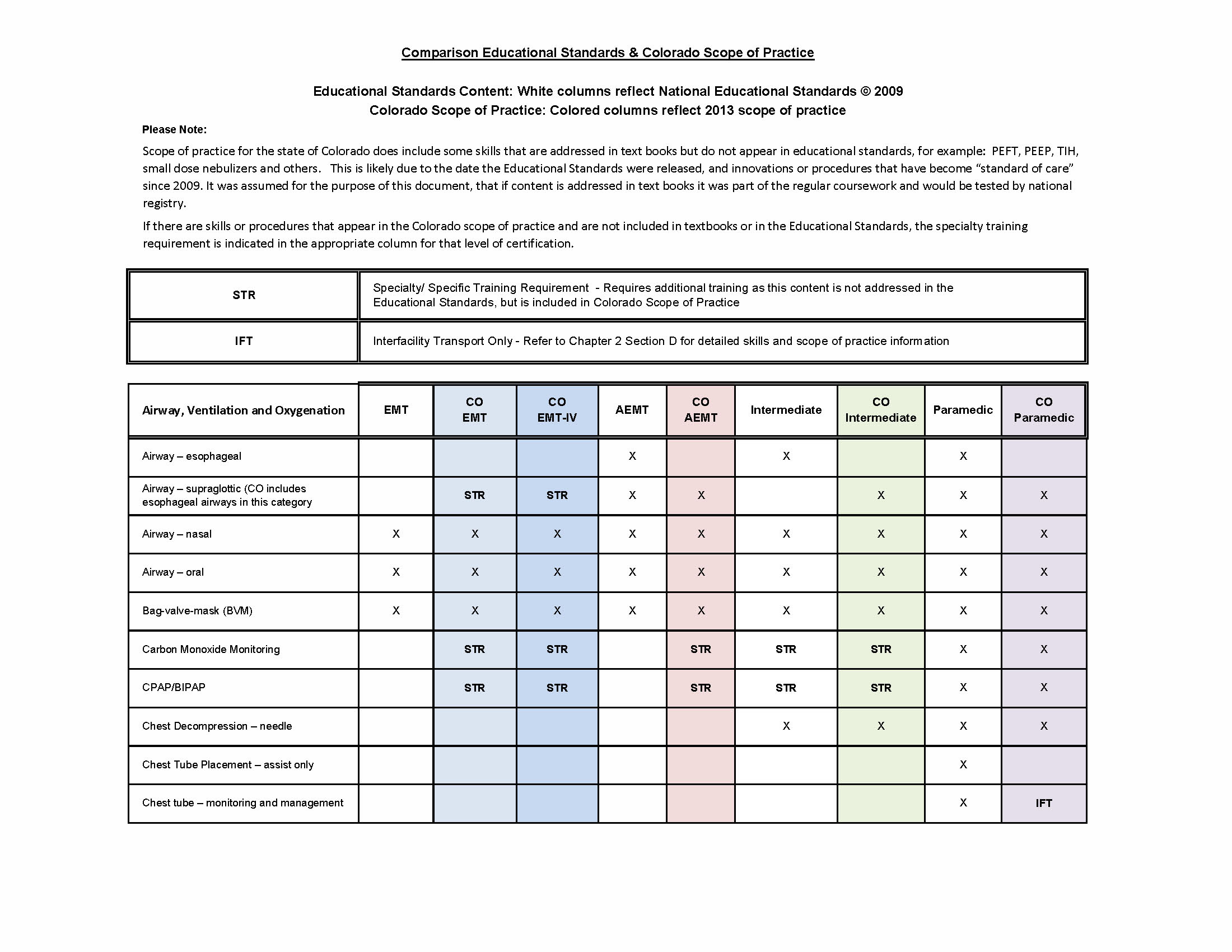

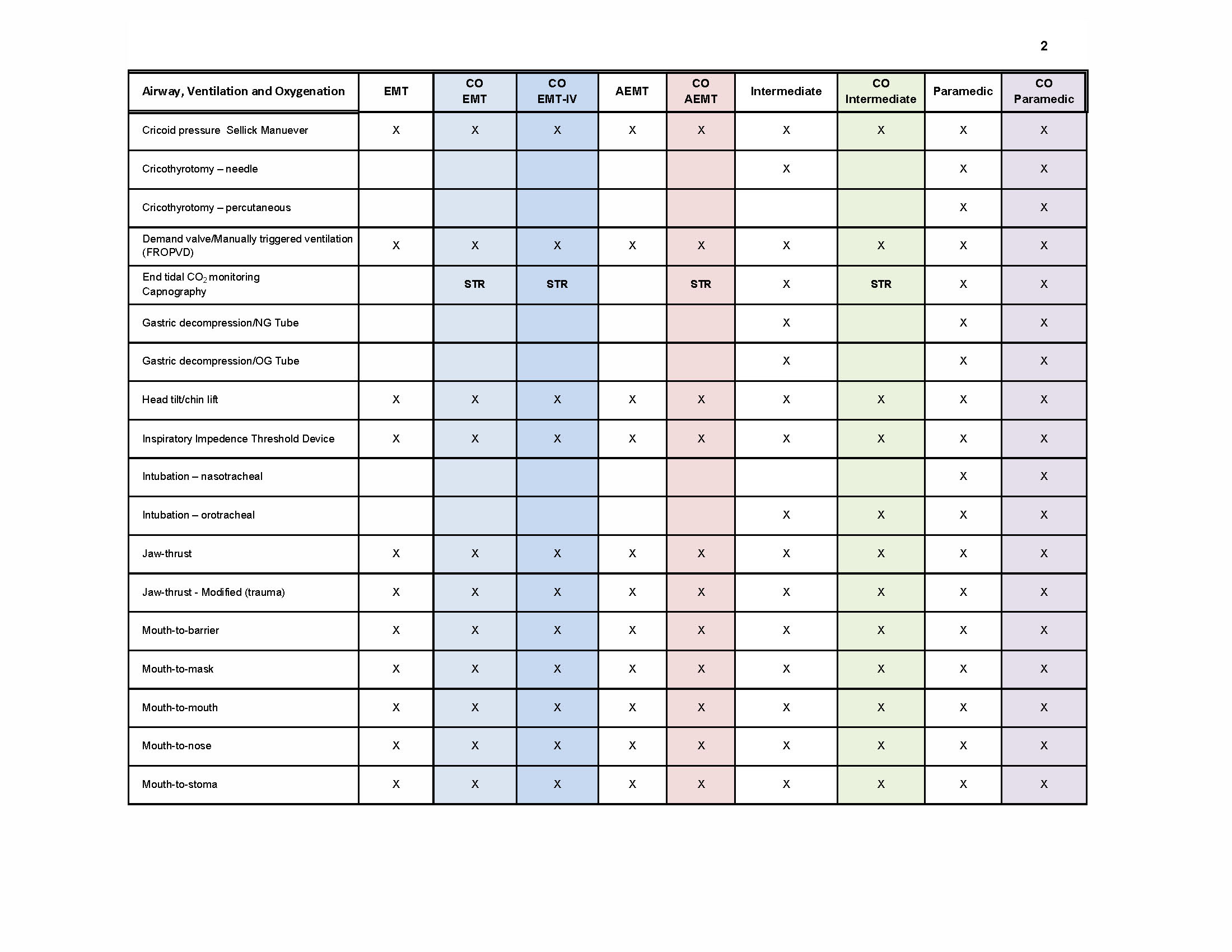

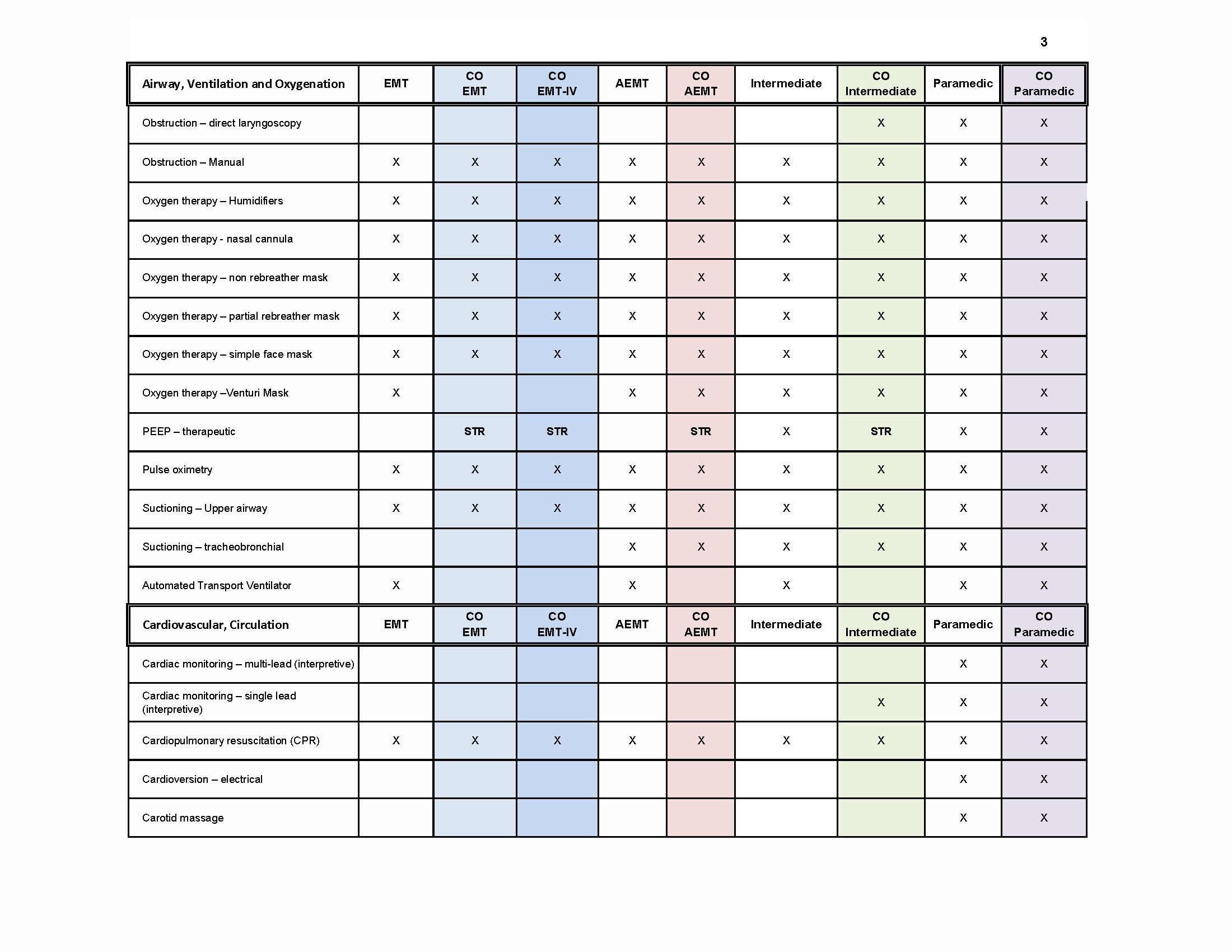

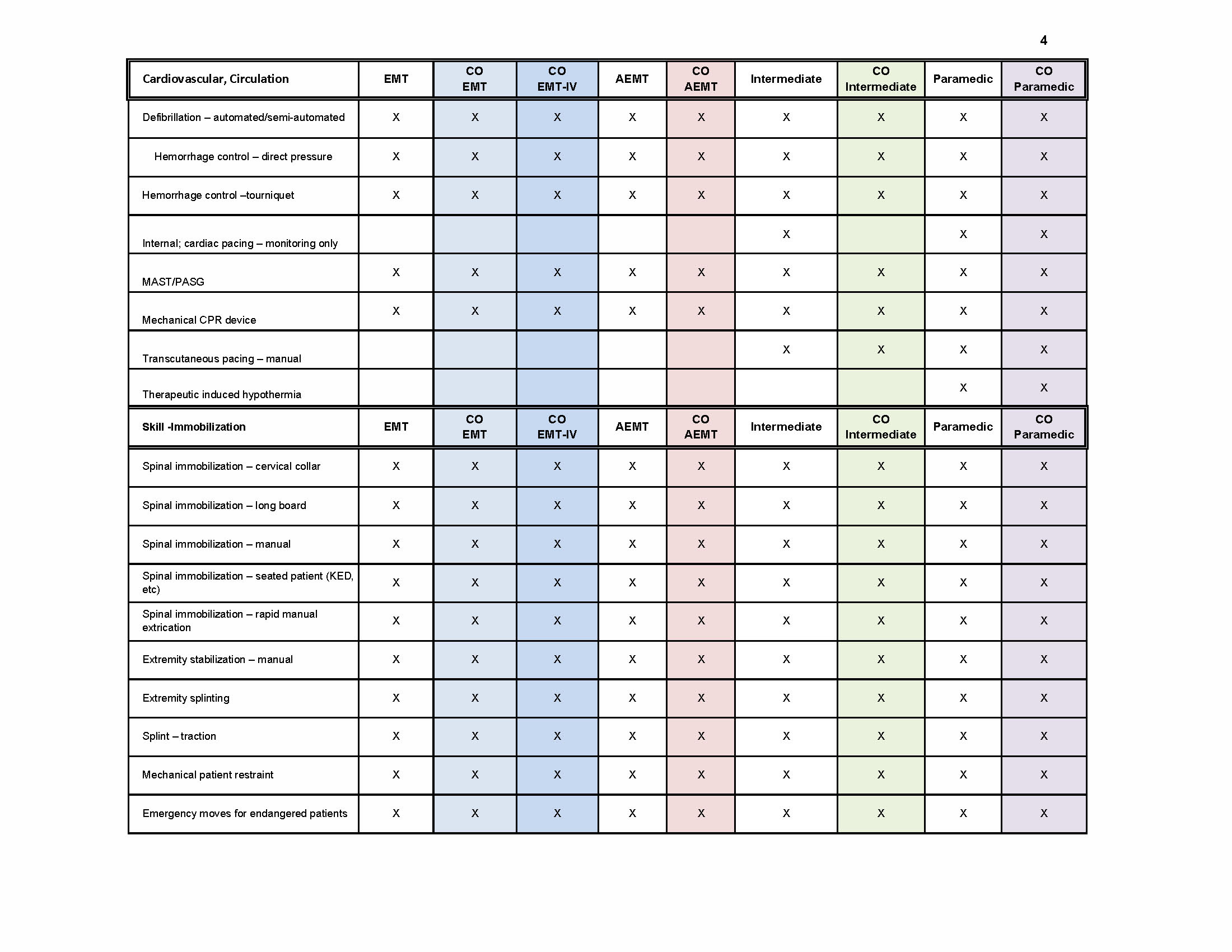

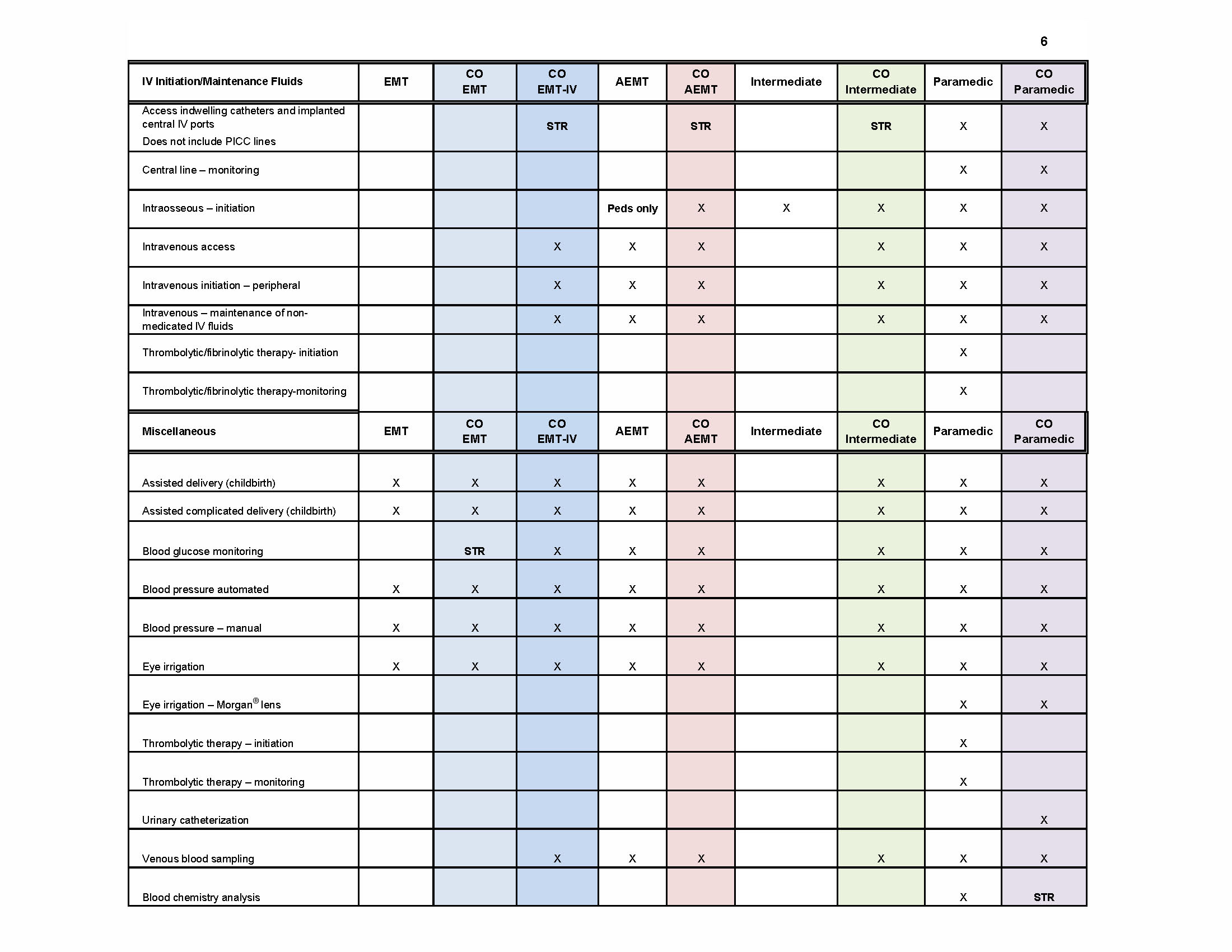

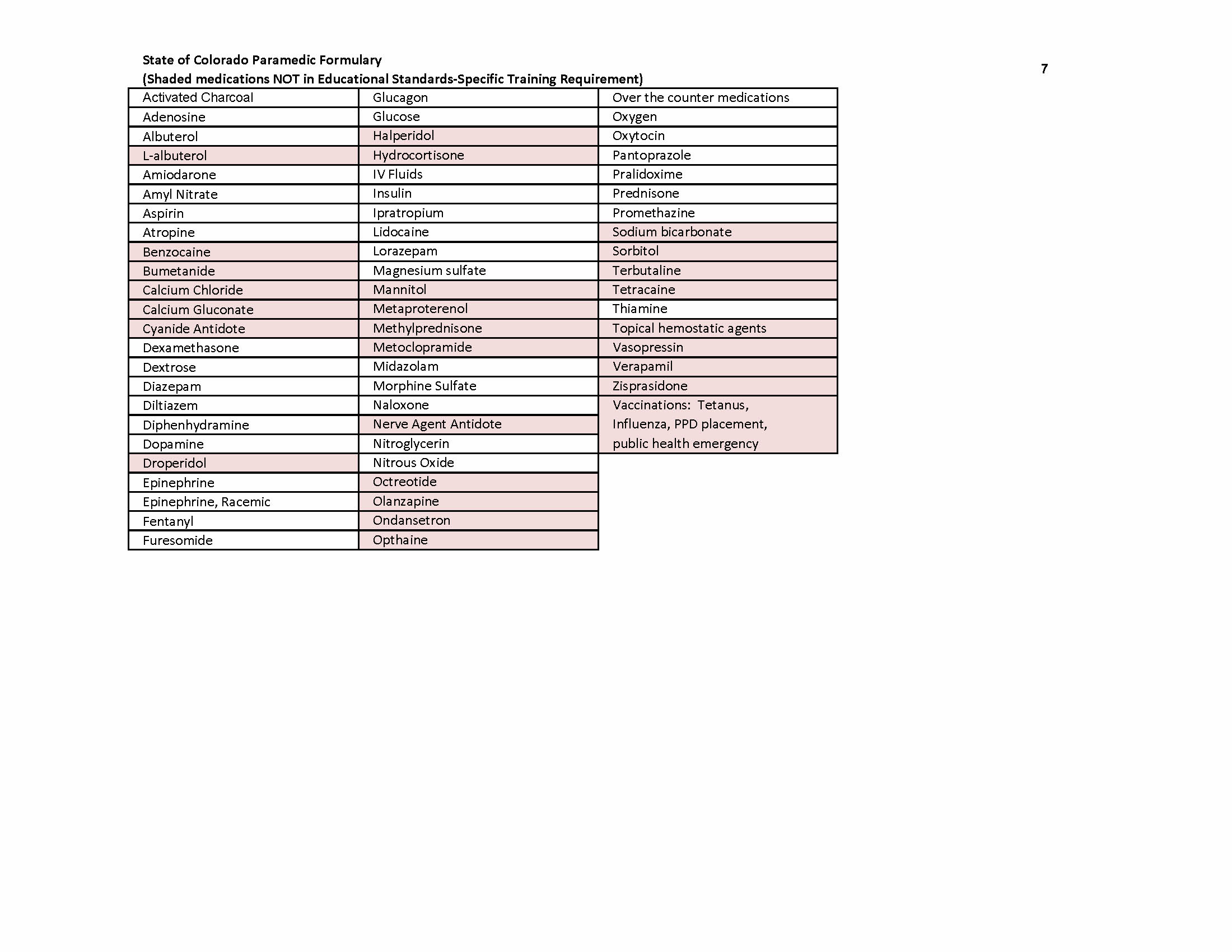

Posted: April 25, 2018 Filed under: Colorado, First Aid, Medical | Tags: AEMT, Emergency medical technician, EMT, EMT-IV, first aid, Intermediate, Paramedic Leave a commentWell Colorado created a great chart so you can understand it.

You can download your own copy of this chart here!

Wilderness Medical Society Trailblazer: If you work in Outdoor Recreation you should be a Member!

Posted: December 21, 2017 Filed under: First Aid, Medical | Tags: first aid, Leaches, Mt. Everest, Wilderness Medical Society, Wilderness Medicine, WMS Leave a comment![]()

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| Virus-free. www.avast.com |

State AED laws may create liability; make sure you understand what your state laws say. Florida, an AED law affecting high schools created liability for the HS.

Posted: December 19, 2016 Filed under: First Aid, Florida, Medical, Sports | Tags: #Soccer, AED, Automatic External Defibrillator, High School Team, Supervision, Use Leave a commentA Florida statute requiring schools to acquire and train all employees on the use of AED’s, created liability when the AED was not used.

State: Florida, Supreme Court of Florida

Plaintiff: Abel Limones, Sr., et al

Defendant: School District of Lee County et al.

Plaintiff Claims: Common Law negligence and breach of a duty required by statute, Florida Statute 1006.165

Defendant Defenses: No duty and Immune under 1006.165 and 768.1325

Holding: for the Plaintiff

Year: 2015

The deceased was a 15-year-old boy who played on a high school soccer team. While playing a high school soccer game he collapsed. His coach ran onto the field and started CPR and was assisted by two nurses who were sitting in the stands.

Allegedly, the coach asked several times for an AED (Automatic External Defibrillator). An AED was located in a storage are at the end of the field. However, no one ever retrieved the AED.

Ten minutes later, the fire department arrived and attempted to revive the student with their AED. That did not work. Twenty-six minutes later, an ambulance arrived and with the application of the ambulance AED and the application of drugs, EMS was able to restore the student’s heart rate.

The plaintiff’s expert witness testified that the 26 minutes without the use of the AED, not having a heartbeat, deprived the student of oxygen, which caused brain damage. The student was left in a persistent vegetative state.

The trial court granted the defendants motion for summary judgment. The plaintiff appealed and the Florida Appellate Court upheld the dismal by the trial court. The Florida Supreme Court then heard the appeal and issued this decision.

Analysis: making sense of the law based on these facts.

The Supreme Court of Florida first looked at basic negligence claims pursuant to Florida’s law. Florida’s law applies the same four steps to prove negligence as most other states.

We have long held that to succeed on a claim of negligence, a plaintiff must establish the four elements of duty, breach, proximate causation, and damages. Of these elements, only the existence of a duty is a legal question because duty is the standard to which the jury compares the conduct of the defendant.

A legal question is one that must be answered by the courts. So whether or not a duty existed, in proving negligence, is first reviewed by the trial judge. Factual questions are reviewed by the finder of fact, most commonly called the jury. Looking at the issue of duty, the court found under Florida Law, there were four sources of duty.

Florida law recognizes the following four sources of duty: (1) statutes or regulations; (2) common law interpretations of those statutes or regulations; (3) other sources in the common law; and (4) the general facts of the case.

Rarely do courts define how duties are created. Consequently, reviewing how a duty is created is interesting. The last way, general facts of the case, are how most duties are determined. The plaintiff argues there is a duty because of how others act or fail to act or based on the testimony from expert witnesses. Alternatively, an organization or trade association has published a list of the standards of care, which are then used to prove the duty failed.

The court then must examine if the minimum requirements for a duty have been met.

As in this case, when the source of the duty falls within the first three sources, the factual inquiry necessary to establish a duty is limited. The court must simply determine whether a statute, regulation, or the common law imposes a duty of care upon the defendant. The judicial determination of the existence of a duty is a minimal threshold that merely opens the courthouse doors.

In this case, the parties were relying on a statute; the Florida Statute that put AED’s in schools and required all school employees to be trained on their use, 768.1325. Once the court determines that a duty existed, then the jury must decide all other issues of the case.

Once a court has concluded that a duty exists, Florida law neither requires nor allows the court to further expand its consideration into how a reasonably prudent person would or should act under the circumstances as a matter of law. We have clearly stated that the remaining elements of negligence–breach, proximate causation, and damages–are to be resolved by the fact-finder.

The court then looked into the duty of schools with regard to students. A special relationship exists between a student (and their parents) and schools. A special relationship then takes the duty out from limited if any duty at all to a specific duty of care. Here that relationship creates a duty upon the school to act as a reasonable man would.

As a general principle, a party does not have a duty to take affirmative action to protect or aid another unless a special relationship exists which creates such a duty. When such a relationship exists, the law requires the party to act with reasonable care toward the person in need of protection or aid. As the Second District acknowledged below, Florida courts have recognized a special relationship between schools and their students based upon the fact that a school functions at least partially in the place of parents during the school day and school-sponsored activities.

The duty thus created or established requires a school to reasonably supervise students.

This special relationship requires a school to reasonably supervise its students during all activities that are subject to the control of the school, even if the activities occur beyond the boundaries of the school or involve adult students.

It should be noted, however, when referring to “school” in this manner; the courts are talking about public schools and students under the age of 18. Colleges have very different duties, especially outside of the classroom or off campus.

That supervision duty schools have, has five sub-elements or additional duties when dealing with student athletes.

Lower courts in Florida have recognized that the duty of supervision creates the following specific duties owed to student athletes: (1) schools must adequately instruct student athletes; (2) schools must provide proper equipment; (3) schools must reasonably match participants; (4) schools must adequately supervise athletic events; and (5) schools must take appropriate measures after a student is injured to prevent aggravation of the injury.

Here, several of the specific duties obviously could be applied to the case. Consequently, the court found the school owed a duty to the deceased.

Having determined the duty owed by the school to the deceased the court held that the school had a duty to the deceased that was breached. The use of an AED, required at the school by statute, was a reasonable duty owed to the deceased.

Therefore, we conclude that Respondent owed Abel a duty of supervision and to act with reasonable care under the circumstances; specifically, Respondent owed Abel a duty to take appropriate post-injury efforts to avoid or mitigate further aggravation of his injury. “Reasonable care under the circumstances” is a standard that may fluctuate with time, the student’s age and activity, the extent of the injury, the available responder(s), and other facts. Advancements with technology and equipment available today, such as a portable AED, to treat an injury were most probably unavailable twenty years ago, and may be obsolete twenty years from now.

The plaintiffs also argued there were additional duties owed based on the Florida School AED statute. However, the court declined to review this issue. Meaning, it is undecided and could go either way in the future.

The defendant then argued they were immune from suit based on the Florida AED Good Samaritan Act. The court then looked at the immunity statute set forth in the Florida School AED Statute. The Statute required schools to have AED’s and have to train all employees in the use of the AED. The court found that employees and volunteers could be covered under the Florida AED Good Samaritan Act. If they used the AED’s they would be immune from suit.

The court in reading the Florida AED Good Samaritan Act found two different groups of people were created by the act. However, only one was protected by the act and immune from suit. Those who use or attempt to use an AED are immune. Those that only acquire the AED, are not immune because they did not attempt to use the AED.

Users are clearly “immune from civil liability for any harm resulting from the use or attempted use” of an AED. § 768.1325(3), Fla. Stat. Additionally, acquirers are immune from “such liability,” meaning the “liability for any harm resulting from the use or attempted use” referenced in the prior sentence. Thus, acquirers are not immune due to the mere fact that they have purchased and made available an AED which has not been used; rather, they are entitled to immunity from the harm that may result only when an AED is actually used or attempted to be used.

That immunity only applied to the use of the AED. Here there was no use of the AED, so the statute did not provide any immunity.

It is undisputed that no actual or attempted use of an AED occurred in this case until emergency responders arrived. Therefore, we hold that Respondent is not entitled to immunity under section 768.1325 and such section has absolutely no application here.

The court summarized its analysis.

We hold that Respondent owed a common law duty to supervise Abel, and that once injured, Respondent owed a duty to take reasonable measures and come to his aid to prevent aggravation of his injury. It is a matter for the jury to determine under the evidence whether Respondent’s actions breached that duty and resulted in the damage that Abel suffered. We further hold Respondent is not entitled to immunity from suit under section 768.1325, Florida Statutes.

So Now What?

So in Florida, a statute that requires someone, such as a school to have AED’s then requires the school to use the AED’s and if they do not, they breach the common law duty of care to their students.

AED laws are going to become a carnival ride in attempting to understand and use them without creating liability or remaining immune from suit. You probably not only want to be on top of the law that is being passed in your state; you should probably go down and testify so the legislature in an attempt to save a life does not sink your business.

It is sad when a young man dies, especially, if he could have been saved. That issue is probably going to trial.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

If you like this let your friends know or post it on FB, Twitter or LinkedIn

Author: Outdoor Recreation Insurance, Risk Management and Law

Copyright 2016 Recreation Law (720) Edit Law

Email: Rec-law@recreation-law.com

Google+: +Recreation

Twitter: RecreationLaw

Facebook: Rec.Law.Now

Facebook Page: Outdoor Recreation & Adventure Travel Law

Blog: www.recreation-law.com

Mobile Site: http://m.recreation-law.com

By Recreation Law Rec-law@recreation-law.com James H. Moss

#AdventureTourism, #AdventureTravelLaw, #AdventureTravelLawyer, #AttorneyatLaw, #Backpacking, #BicyclingLaw, #Camps, #ChallengeCourse, #ChallengeCourseLaw, #ChallengeCourseLawyer, #CyclingLaw, #FitnessLaw, #FitnessLawyer, #Hiking, #HumanPowered, #HumanPoweredRecreation, #IceClimbing, #JamesHMoss, #JimMoss, #Law, #Mountaineering, #Negligence, #OutdoorLaw, #OutdoorRecreationLaw, #OutsideLaw, #OutsideLawyer, #RecLaw, #Rec-Law, #RecLawBlog, #Rec-LawBlog, #RecLawyer, #RecreationalLawyer, #RecreationLaw, #RecreationLawBlog, #RecreationLawcom, #Recreation-Lawcom, #Recreation-Law.com, #RiskManagement, #RockClimbing, #RockClimbingLawyer, #RopesCourse, #RopesCourseLawyer, #SkiAreas, #Skiing, #SkiLaw, #Snowboarding, #SummerCamp, #Tourism, #TravelLaw, #YouthCamps, #ZipLineLawyer, AED, Automatic External Defibrillator, Soccer, High School Team, Supervision, Use,

Limones, Sr., et al., v. School District of Lee County et al., 161 So. 3d 384; 2015 Fla. LEXIS 625; 40 Fla. L. Weekly S 182

Posted: December 18, 2016 Filed under: First Aid, Florida, Medical, Sports | Tags: #Soccer, AED, Automatic External Defibrillator, High School Team Leave a commentLimones, Sr., et al., v. School District of Lee County et al., 161 So. 3d 384; 2015 Fla. LEXIS 625; 40 Fla. L. Weekly S 182

Abel Limones, Sr., et al., Petitioners, vs. School District of Lee County et al., Respondents.

No. SC13-932

SUPREME COURT OF FLORIDA

161 So. 3d 384; 2015 Fla. LEXIS 625; 40 Fla. L. Weekly S 182

April 2, 2015, Decided

PRIOR HISTORY: [**1] Application for Review of the Decision of the District Court of Appeal – Direct Conflict of Decisions. Second District – Case No. 2D11-5191. (Lee County).

Limones v. Sch. Dist. of Lee County, 111 So. 3d 901, 2013 Fla. App. LEXIS 1821 (Fla. Dist. Ct. App. 2d Dist., 2013)

COUNSEL: David Charles Rash of David C. Rash, P.A., Weston, Florida, and Elizabeth Koebel Russo of Russo Appellate Firm, P.A., Miami, Florida, for Petitioners.

Traci McKee of Henderson, Franklin, Starnes & Holt, P.A., Fort Myers, Florida, and Scott Andrew Beatty of Henderson, Franklin, Starnes & Holt, P.A., Bonita Springs, Florida, for Respondents.

Jennifer Suzanne Blohm and Ronald Gustav Meyer of Meyer, Brooks, Demma and Blohm, P.A., Tallahassee, Florida, for Amicus Curiae Florida School Boards Association, Inc.

Leonard E. Ireland, Jr., Gainesville, Florida, for Amicus Curiae Florida High School Athletic Association, Inc.

Mark Miller and Christina Marie Martin, Pacific Legal Foundation, Palm Beach Gardens, Florida, for Amicus Curiae Pacific Legal Foundation.

JUDGES: LABARGA, C.J., and PARIENTE, QUINCE, and PERRY, JJ., concur. CANADY, J., dissents with an opinion, in which POLSTON, J., concurs.

OPINION BY: LEWIS

OPINION

[*387] LEWIS, J.

Petitioners Abel Limones, Sr., and Sanjuana Castillo seek review of the decision of the Second District Court of Appeal in Limones v. School District of Lee County, 111 So. 3d 901 (Fla. 2d DCA 2013), asserting that it expressly [**2] and directly conflicts with the decision of this Court in McCain v. Florida Power Corp., 593 So. 2d 500 (Fla. 1992), and several other Florida decisions.

BACKGROUND

At approximately 7:40 p.m. on November 13, 2008, fifteen-year-old Abel Limones, Jr., suddenly collapsed during a high school soccer game. There is no evidence in the record to suggest that Abel collapsed due to a collision with another player. The event involved a soccer game between East Lee County High School, Abel’s school, and Riverdale High School, the host school. Both schools belong to the School District of Lee County. When Abel was unable to rise, Thomas Busatta, the coach for East Lee County High School, immediately ran onto the field to check his player. Abel tried to speak to Busatta, but within three minutes of the collapse, he appeared to stop breathing and lost consciousness. Busatta was unable to detect a pulse. An administrator from Riverdale High School who called 911, and two parents in the stands who were nurses, joined Busatta on the field. Busatta and one nurse began to perform cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) on Abel. Busatta, who was certified in the use of an automated external defibrillator (AED), testified that he yelled for an AED. The AED in the [**3] possession of Riverdale High School was actually at the game facility located at the end of the soccer field, but it was never brought on the field to Busatta to assist in reviving Abel.

Emergency responders from the fire department arrived at approximately 7:50 p.m. and applied their semi-automatic AED to revive Abel, but that was unsuccessful. Next, responders from the Emergency Medical Service (EMS) arrived and utilized a fully automatic AED on Abel and also administered several drugs in an attempt to restore his heartbeat. After application of shocks and drugs, emergency responders revived Abel, but not until approximately 8:06 p.m., which was twenty-six minutes after his initial collapse. Although Abel survived, he suffered a severe brain injury due to a lack of oxygen over the time delay involved. As a result, he now remains in a nearly persistent vegetative state that will require full-time care for the remainder of his life.

Petitioners, Abel’s parents, retained an expert, Dr. David Systrom, M.D., who determined that Abel suffered from a previously undetected underlying heart condition. Dr. Systrom further opined that if shocks from an AED had been administered earlier, oxygen [**4] would have been restored [*388] to Abel’s brain sooner and he would not have suffered the brain injury that left him in the current permanent vegetative state. Petitioners then filed an action against Respondent, the School Board of Lee County.1 They alleged that Respondent breached both a common law duty and a statutory duty as imposed by section 1006.165, Florida Statutes (2008),2 when it failed to apply an AED on Abel after his collapse. The School Board moved for summary judgment, which the trial court granted and entered final judgment.

1 Petitioners initially filed an action against the School District of Lee County and the School Board of Lee County. All parties conceded that the only proper respondent in this case is the School Board of Lee County.

2 [HN1] Section 1006.165, Florida Statutes, requires all public schools that participate in the Florida High School Athletic Association to acquire an AED, train personnel in its use, and register its location with the local EMS.

On appeal, the Second District recognized that Respondent owed a duty to supervise its students, which in the context of student athletes included a duty to prevent aggravation of an injury. Limones, 111 So. 3d at 904-05 (citing Rupp v. Bryant, 417 So. 2d 658 (Fla. 1982); Leahy v. Sch. Bd. of Hernando Cnty., 450 So. 2d 883, 885 (Fla. 5th DCA 1984)). However, the Second District proceeded to expand its consideration of the duty owed and enlarged [**5] its consideration into a factual scope, extent, and performance of that duty analysis. Id. at 905 (citing Cerny v. Cedar Bluffs Junior/Senior Pub. Sch., 262 Neb. 66, 628 N.W.2d 697, 703 (Neb. 2001)). In this analysis, the Second District considered and evaluated whether post-injury efforts in connection with satisfying the duty to Abel should have included making available, diagnosing the need for, or using an AED. Id. The Second District relied on the discussion provided by the Fourth District Court of Appeal in L.A. Fitness International, LLC v. Mayer, 980 So. 2d 550 (Fla. 4th DCA 2008), even though that case did not consider the same “duty” and the health club did not have a duty involving students or any similar relationship.

In L.A. Fitness, the Fourth District considered whether a health club breached its duty of reasonable care owed to a customer who was using training equipment when the health club failed to acquire or use an AED on a customer in cardiac distress. Id. at 556-57. After a review of the common law duties owed by a business owner to its invitees, the Fourth District determined that a health club owed no duty to provide or use an AED on a patron in cardiac distress. Id. at 562. The Second District in Limones found no distinction between L.A. Fitness and the present case, even though the differences are extreme, and concluded that reasonably prudent post-injury [**6] efforts did not require Respondent to provide, diagnose the need for, or use an AED. Limones, 111 So. 3d at 906. The Second District also determined that neither the undertaker’s doctrine3 nor section 1006.165, Florida Statutes, imposed a duty to use an AED on Abel. Id. at 906-07. Finally, after it concluded that Respondent was immune from civil liability under section 768.1325(3), Florida Statutes (2008), the Second District affirmed the decision [*389] of the trial court. Id. at 908-09. This review follows.

3 [HN2] The undertaker’s doctrine imposes a duty of reasonable care upon a party that freely or by contract undertakes to perform a service for another party. See, e.g., Clay Elec. Coop., Inc. v. Johnson, 873 So. 2d 1182, 1186 (Fla. 2003) (citing Restatement (Second) of Torts § 323 (1965)). The undertaker is subject to liability if: (a) he or she fails to exercise reasonable care, which results in increased harm to the beneficiary; or (b) the beneficiary relies upon the undertaker and is harmed as a result. See id.

ANALYSIS

Jurisdiction

We first consider whether jurisdiction exists to review this matter. Petitioners assert that the decision below expressly and directly conflicts with the decision of this Court in McCain and other Florida decisions. See art. V, § 3(b)(3), Fla. Const. Specifically, Petitioners claim that the Second District defined the duty in a manner that conflicts with the approach delineated in McCain. We agree.

We have long [**7] held that [HN3] to succeed on a claim of negligence, a plaintiff must establish the four elements of duty, breach, proximate causation, and damages. See, e.g., U.S. v. Stevens, 994 So. 2d 1062, 1065-66 (Fla. 2008). Of these elements, only the existence of a duty is a legal question because duty is the standard to which the jury compares the conduct of the defendant. McCain, 593 So. 2d at 503. Florida law recognizes the following four sources of duty: (1) statutes or regulations; (2) common law interpretations of those statutes or regulations; (3) other sources in the common law; and (4) the general facts of the case. Id. at 503 n.2. As in this case, when the source of the duty falls within the first three sources, the factual inquiry necessary to establish a duty is limited.4 The court must simply determine whether a statute, regulation, or the common law imposes a duty of care upon the defendant. The judicial determination of the existence of a duty is a minimal threshold that merely opens the courthouse doors. Id. at 502. Once a court has concluded that a duty exists, Florida law neither requires nor allows the court to further expand its consideration into how a reasonably prudent person would or should act under the circumstances as a matter of law.5 We have clearly stated that the [**8] remaining elements of negligence–breach, proximate causation, and damages–are to be resolved by the fact-finder. See Dorsey v. Reider, 139 So. 3d 860, 866 (Fla. 2014); Williams v. Davis, 974 So. 2d 1052, 1056 n.2 (Fla. 2007) (citing McCain, 593 So. 2d at 504); see also Orlando Exec. Park, Inc. v. Robbins, 433 So. 2d 491, 493 (Fla. 1983) (“[I]t is peculiarly a jury function to determine what precautions are reasonably required in the exercise of a particular duty of due care.” (citation omitted)), receded from on other grounds by Mobil Oil Corp. v. Bransford, 648 So. 2d 119, 121 (Fla. 1995).

4 [HN4] Even when the duty is rooted in the fourth prong, factual inquiry into the existence of a duty is limited to whether the “defendant’s conduct foreseeably created a broader ‘zone of risk’ that poses a general threat of harm to others.” McCain, 593 So. 2d at 502.

5 Of course, as McCain acknowledges, [HN5] some facts must be established to determine whether a duty exists, such as the identity of the parties, their relationship, and whether that relationship qualifies as a special relationship recognized by tort law and subject to heightened duties. See 593 So. 2d at 503-04. However, further factual inquiry risks invasion of the province of the jury.

The Second District determined that a clearly recognized common law duty existed under both Rupp and Leahy. Rupp established that [HN6] school employees must reasonably supervise students during activities that are subject to the control of the school. 417 So. 2d at 666; see also Leahy, 450 So. 2d at 885 (explaining [**9] that the duty of supervision owed by a school to its students included a duty to prevent aggravation of an injury). [HN7] However, the Second District incorrectly expanded Florida law and invaded the province of the [*390] jury when it further considered whether post-injury efforts required Respondent to make available, diagnose the need for, or use the AED on Abel. Limones, 111 So. 3d at 905. This detailed analysis exceeded the threshold requirement that this Court established in McCain. Therefore, conflict jurisdiction exists to consider the merits of this case and we choose to exercise our discretion to resolve this conflict. [HN8] We review de novo rulings on summary judgment with respect to purely legal questions. See, e.g., Clay Elec. Coop., Inc. v. Johnson, 873 So. 2d 1182, 1185 (Fla. 2003).

Common Law Duty

[HN9] As a general principle, a party does not have a duty to take affirmative action to protect or aid another unless a special relationship exists which creates such a duty. See Restatement (Second) of Torts § 314 cmt. a (1965). When such a relationship exists, the law requires the party to act with reasonable care toward the person in need of protection or aid. See id. § 314A cmt. e. As the Second District acknowledged below, Florida courts have recognized a special relationship between schools and their students based upon the fact that [**10] a school functions at least partially in the place of parents during the school day and school-sponsored activities. See, e.g., Nova Se. Univ., Inc. v. Gross, 758 So. 2d 86, 88-89 (Fla. 2000) (citing Rupp, 417 So. 2d at 666). Mandatory education of children also supports this relationship. Rupp, 417 So. 2d at 666.

[HN10] This special relationship requires a school to reasonably supervise its students during all activities that are subject to the control of the school, even if the activities occur beyond the boundaries of the school or involve adult students. See Nova Se. Univ., 758 So. 2d at 88-89 (applying the in loco parentis doctrine to a relationship between an adult student and a university when the university mandated participation by the student in an off-campus internship); Rupp, 417 So. 2d at 666-67 (concluding that a duty of supervision existed during an unsanctioned off-campus hazing event by a school-sponsored club); cf. Kazanjian v. Sch. Bd. of Palm Beach Cnty., 967 So. 2d 259, 268 (Fla. 4th DCA 2007) (finding that the duty of supervision did not extend to a student who was injured when she left school premises without authorization). This duty to supervise requires teachers and other applicable school employees to act with reasonable care under the circumstances. Wyke v. Polk Cnty. Sch. Bd., 129 F.3d 560, 571 (11th Cir. 1997) (citing Florida law); see also Nova Se. Univ., 758 So. 2d at 90 (noting that the university had a duty to use reasonable care when it assigned students to off-campus internships). Thereafter, it [**11] is for the jury to determine whether, under the relevant circumstances, the school employee has acted unreasonably and, therefore, breached the duty owed. See La Petite Acad., Inc. v. Nassef ex rel. Knippel, 674 So. 2d 181, 182 (Fla. 2d DCA 1996) (citing Benton v. Sch. Bd. of Broward Cnty., 386 So. 2d 831, 834 (Fla. 4th DCA 1980)); see also Zalkin v. Am. Learning Sys., 639 So. 2d 1020, 1021 (Fla. 3d DCA 1994) (concluding that whether alleged negligent supervision by school employees resulted in injury to a student was a jury issue).

[HN11] Lower courts in Florida have recognized that the duty of supervision creates the following specific duties owed to student athletes: (1) schools must adequately instruct student athletes; (2) schools must provide proper equipment; (3) schools must reasonably match participants; (4) schools must adequately supervise athletic events; and (5) schools must take appropriate measures after a student is injured to prevent aggravation of the injury. See [*391] Limones, 111 So. 3d at 904 (citing Leahy, 450 So. 2d at 885); see also Zalkin, 639 So. 2d at 1021. Other jurisdictions have acknowledged similar duties owed to student athletes. See Avila v. Citrus Cmty. Coll. Dist., 38 Cal. 4th 148, 41 Cal. Rptr. 3d 299, 131 P.3d 383, 392 (Cal. 2006) (“[I]n interscholastic and intercollegiate competition, the host school and its agents owe a duty to home and visiting players alike to, at a minimum, not increase the risks inherent in the sport.”); Kleinknecht v. Gettysburg Coll., 989 F.2d 1360, 1370 (3d Cir. 1993) (college owed duty to recruited athlete to take reasonable safety precautions against the risk of death); see also Jarreau v. Orleans Parish School Bd., 600 So. 2d 1389, 1393 (La. Ct. App. 1992) (school board owed duty to [**12] injured high school athlete to provide access to medical treatment); Stineman v. Fontbonne Coll., 664 F.2d 1082, 1086 (8th Cir. 1981) (college owed duty to provide medical assistance to injured student athlete).

In this case, Abel was a student who was injured while he participated in a school-sponsored soccer game under the supervision of school officials. Therefore, we conclude that Respondent owed Abel a duty of supervision and to act with reasonable care under the circumstances; specifically, Respondent owed Abel a duty to take appropriate post-injury efforts to avoid or mitigate further aggravation of his injury. See Rupp, 417 So. 2d at 666; Leahy, 450 So. 2d at 885. “Reasonable care under the circumstances” is a standard that may fluctuate with time, the student’s age and activity, the extent of the injury, the available responder(s), and other facts. Advancements with technology and equipment available today, such as a portable AED, to treat an injury were most probably unavailable twenty years ago, and may be obsolete twenty years from now. We therefore leave it to the jury to determine, under the evidence presented, whether the particular actions of Respondent’s employees satisfied or breached the duty of reasonable care owed.

For several reasons, we reject the decision of the Second [**13] District to narrowly frame the issue as whether Respondent had a specified duty to diagnose the need for or use an AED on Abel. First, as stated above, reasonable care under the circumstances is not and should not be a fixed concept. Such a narrow definition of duty, a purely legal question, slides too easily into breach, a factual matter for the jury. See McCain, 593 So. 2d at 502-04. We reject the attempt below to specifically define each element in the scope of the duty as a matter of law, as this case attempted to remove all factual elements from the law and digitalize every aspect of human conduct. We are also cognizant of the concern raised by Respondent and its amici that if a defined duty could require every high school to provide an AED at every athletic practice and contest, the result could be great expense. Instead, the flexible nature of reasonable care delineated here can be evaluated on a case by case basis. The duty does not change with regard to using reasonable care to supervise and assist students, but the methods and means of fulfilling that duty will depend on the circumstances.

Additionally, we reject the position of the Second District and Respondent that L.A. Fitness governs this case. [**14] The Fourth District in L.A. Fitness determined that the duty owed by a commercial health club to an adult customer only required employees of the club to reasonably summon emergency responders for a patron in cardiac distress. 980 So. 2d at 562; see also De La Flor v. Ritz-Carlton Hotel Co., 930 F. Supp. 2d 1325, 1330 (S.D. Fla. 2013) (citing L.A. Fitness, 980 So. 2d at 562). [*392] The adult customer and the health club stand in a far different relationship than a student involved in school activities with school board officials. Although some courts in other jurisdictions have determined that fitness clubs and other commercial entities do not owe a legal duty to provide AEDs to adult customers,6 the commercial context and relationship of parties in these cases is a critical distinction from the case before us. Despite the fact the business proprietor-customer and school district-student relationships are both recognized as relationships, these relationships are markedly different. We initially note that the proprietor-customer relationship most frequently involves two adult parties, whereas the school-student relationship usually involves a minor. Furthermore, the business invitee freely enters into a commercial relationship with the proprietor.

6 See, e.g., Verdugo v. Target Corp., 59 Cal. 4th 312, 173 Cal. Rptr. 3d 662, 327 P.3d 774, 792 (Cal. 2014) (holding that a retailer did not owe a common law duty to [**15] acquire and make available an AED to a patron); Miglino v. Bally Total Fitness of Greater N.Y., Inc., 20 N.Y.3d 342, 985 N.E.2d 128, 132, 961 N.Y.S.2d 364 (N.Y. 2013) (statute that required large health clubs to acquire an AED did not impose duty to use it); Rotolo v. San Jose Sports & Entm’t, LLC, 151 Cal. App. 4th 307, 59 Cal. Rptr. 3d 770, 774-75 (Cal. Ct. App. 2007) (refusing to impose a duty on owners of a sports facility to notify patrons of the existence and location of an AED), modified on other grounds by Verdugo, 327 P.3d at 784; Salte v. YMCA of Metro. Chi. Found., 351 Ill. App. 3d 524, 814 N.E.2d 610, 615, 286 Ill. Dec. 622 (Ill. App. Ct. 2004) (holding that a health club’s duty of reasonable care to its guests did not require it to obtain and use an AED on a guest).

By contrast, [HN12] Florida, along with the rest of the country, has mandated education of our minor children. § 1003.21, Fla. Stat. (2014). Compulsory schooling creates a unique relationship, a fact that has been recognized both by Florida courts and the Florida Legislature. Florida common law recognizes a specific duty of supervision owed to students and a duty to aid students that is not otherwise owed to the business customer. See Rupp, 417 So. 2d at 666-67. Furthermore, the Florida Legislature has specifically mandated that high schools that participate in interscholastic athletics acquire an AED and train appropriate personnel in its use. § 1006.165(1)-(2), Fla. Stat. Notably, the Legislature has not so regulated health clubs or other commercial facilities, even though the foreseeability for the need to use an AED may be similar in both contexts. See [**16] L.A. Fitness, 980 So. 2d at 561. The relationship between a commercial entity and its patron quite simply cannot be compared to that between a school and its students. We therefore conclude that the facts of this case are not comparable to those in L.A. Fitness.

Other Sources of Duty

Although Petitioners alleged in their pleadings that Respondent owed a statutory duty under section 1006.165, Florida Statutes, Petitioners did not clearly articulate before this Court the basis for such a duty. We therefore do not address it here. See, e.g., Chamberlain v. State, 881 So. 2d 1087, 1103 (Fla. 2004). Moreover, because we decide as a dispositive issue that Respondent’s motion for summary judgment was improperly granted because Respondent owed a common law duty to Abel, we decline to address Petitioners’ claim under the undertaker’s doctrine.

Immunity

Because we conclude that Respondent owed a common law duty to Abel, we must now consider whether Respondent is immune from suit under sections 1006.165 and 768.1325, Florida Statutes. [*393] See Wallace v. Dean, 3 So. 3d 1035, 1044 (Fla. 2009) (emphasizing that the existence of a duty is “conceptually distinct” from the determination of whether a party is entitled to immunity). Respondent claims that these statutory provisions grant it immunity. [HN13] The question of statutory immunity is a legal question that we review de novo. See, e.g., Found. Health v. Westside EKG Assocs., 944 So. 2d 188, 193-94 (Fla. 2006).

[HN14] Section 1006.165 requires all public schools [**17] that are members of the Florida High School Athletic Association to have an operational AED on school property and to train “all employees or volunteers who are reasonably expected to use the device” in its application. § 1006.165(1)-(2), Fla. Stat. Further, “[t]he use of [AEDs] by employees and volunteers is covered under [sections] 768.13 and 768.1325,” which generally regulate immunity under Florida’s Good Samaritan Act and the Cardiac Arrest Survival Act. § 1006.165(4).7 Subsection (3) of the Cardiac Arrest Survival Act states:

[HN15] Notwithstanding any other provision of law to the contrary, and except as provided in subsection (4), any person who uses or attempts to use an [AED] on a victim of a perceived medical emergency, without objection of the victim of the perceived medical emergency, is immune from civil liability for any harm resulting from the use or attempted use of such device. In addition, notwithstanding any other provision of law to the contrary, and except as provided in subsection (4), any person who acquired the device and makes it available for use, including, but not limited to, a community organization . . . is immune from such liability . . . .

§ 768.1325(3), Fla. Stat. (emphasis supplied). There is no immunity for criminal misuse, gross negligence, or similarly egregious misuse of an AED. § 768.1325(4)(a).

7 Although section 1006.165 references [**18] both the Good Samaritan Act, section 768.13, and the Cardiac Arrest Survival Act, section 768.1325, Respondent seeks immunity only under the Cardiac Arrest Survival Act. We therefore do not consider whether the Good Samaritan Act provides immunity under these circumstances. See, e.g., Chamberlain, 881 So. 2d at 1103.

[HN16] Under a plain reading of the statute, this subsection creates two classes of parties that may be immune from liability arising from the misuse of AEDs: users (actual or attempted), and acquirers. Users are clearly “immune from civil liability for any harm resulting from the use or attempted use” of an AED. § 768.1325(3), Fla. Stat. Additionally, acquirers are immune from “such liability,” meaning the “liability for any harm resulting from the use or attempted use” referenced in the prior sentence. Id. (emphasis supplied). Thus, acquirers are not immune due to the mere fact that they have purchased and made available an AED which has not been used; rather, they are entitled to immunity from the harm that may result only when an AED is actually used or attempted to be used. It is undisputed that no actual or attempted use of an AED occurred in this case until emergency responders arrived. Therefore, we hold that Respondent is not entitled to immunity under [**19] section 768.1325 and such section has absolutely no application here.

Despite the protests of Respondent and its amici, we do not believe that this straightforward reading of the statute defeats the legislative intent. The passage of section 1006.165 demonstrates that the Legislature was clearly concerned about the risk of cardiac arrest among high school athletes. The Legislature also explicitly [*394] linked this statute to the Cardiac Arrest Survival Act, which grants immunity for the use–actual or attempted–of an AED. The emphasis on the use or attempted use of an AED in the statute underscores the intent of the Legislature to encourage bystanders to use a potentially life-saving AED when appropriate. Without this grant of immunity, bystanders would arguably be more likely to hesitate to use an AED for fear of potential liability. To extend the shield of immunity to those who make no attempt to use an AED would defeat the intended purpose of the statute and discourage the use of AEDs in emergency situations. The argument that immunity applies when an AED is not used is spurious. The immunity is with regard to harm caused by the use of an AED, not a failure to otherwise use reasonable care.

CONCLUSION

We hold that Respondent [**20] owed a common law duty to supervise Abel, and that once injured, Respondent owed a duty to take reasonable measures and come to his aid to prevent aggravation of his injury. It is a matter for the jury to determine under the evidence whether Respondent’s actions breached that duty and resulted in the damage that Abel suffered. We further hold Respondent is not entitled to immunity from suit under section 768.1325, Florida Statutes. We therefore quash the decision below and remand this case for trial.

It is so ordered.

LABARGA, C.J., and PARIENTE, QUINCE, and PERRY, JJ., concur.

CANADY, J., dissents with an opinion, in which POLSTON, J., concurs.

DISSENT BY: CANADY

DISSENT

CANADY, J., dissenting.

Because I conclude that the decision of the district court of appeal, Limones v. School District of Lee County, 111 So. 3d 901 (Fla. 2d DCA 2013), does not expressly and directly conflict with McCain v. Florida Power Corp., 593 So. 2d 500 (Fla. 1992), I would dismiss review of this case for lack of jurisdiction under article V, section 3(b)(3), of the Florida Constitution. I therefore dissent.

In McCain, the plaintiff was injured when the blade of a trencher he was operating made contact with an underground electrical cable owned by Florida Power Corporation. The Court held that because cables transmitting electricity had “unquestioned power to kill or maim,” the defendant had created a “foreseeable zone of risk” and therefore, as a matter [**21] of law, had a duty to take reasonable precautions to prevent injury to others. McCain, 593 So. 2d at 503-04. In Limones, the district court of appeal held as a matter of law that a school district “had no common law duty to make available, diagnose the need for, or use” an automated external defibrillator on a student athlete who “collapsed on the field . . . stopped breathing and had no discernible pulse” during a high school soccer match. Limones, 111 So. 3d at 903, 906. The two decisions are clearly distinguishable based on their totally different facts. Therefore, there is no express and direct conflict and we lack jurisdiction to review the district court’s decision. POLSTON, J., concurs.

Florida AED Statute for Schools

Posted: December 18, 2016 Filed under: First Aid, Florida, Medical | Tags: AED, AED Good Samaritan Act, Automatic External Defibrillator, Good Samaritan law Leave a commentFla. Stat. § 1006.165 (2016)

§ 1006.165. Automated external defibrillator; user training.

(1) Each public school that is a member of the Florida High School Athletic Association must have an operational automated external defibrillator on the school grounds. Public and private partnerships are encouraged to cover the cost associated with the purchase and placement of the defibrillator and training in the use of the defibrillator.

(2) Each school must ensure that all employees or volunteers who are reasonably expected to use the device obtain appropriate training, including completion of a course in cardiopulmonary resuscitation or a basic first aid course that includes cardiopulmonary resuscitation training, and demonstrated proficiency in the use of an automated external defibrillator.

(3) The location of each automated external defibrillator must be registered with a local emergency medical services medical director.

(4) The use of automated external defibrillators by employees and volunteers is covered under ss. 768.13 and 768.1325.

Florida AED Good Samaritan Act

Posted: December 18, 2016 Filed under: First Aid, Florida, Medical | Tags: AED, AED Good Samaritan Act, Automatic External Defibrillator, Florida, Florida Supreme Court Leave a commentFla. Stat. § 768.1325 (2016)

§ 768.1325. Cardiac Arrest Survival Act; immunity from civil liability.

(1) This section may be cited as the “Cardiac Arrest Survival Act.”

(2) As used in this section: