Do Releases Work? Should I be using a Release in my Business? Will my customers be upset if I make them sign a release?

Posted: May 18, 2021 Filed under: Activity / Sport / Recreation, Adventure Travel, Assumption of the Risk, Avalanche, Camping, Challenge or Ropes Course, Climbing, Climbing Wall, Contract, Cycling, Equine Activities (Horses, Donkeys, Mules) & Animals, First Aid, Health Club, Indoor Recreation Center, Insurance, Jurisdiction and Venue (Forum Selection), Medical, Minors, Youth, Children, Mountain Biking, Mountaineering, Paddlesports, Playground, Racing, Racing, Release (pre-injury contract not to sue), Risk Management, Rivers and Waterways, Rock Climbing, Scuba Diving, Sea Kayaking, Search and Rescue (SAR), Ski Area, Skier v. Skier, Skiing / Snow Boarding, Skydiving, Paragliding, Hang gliding, Snow Tubing, Sports, Summer Camp, Swimming, Triathlon, Whitewater Rafting, Youth Camps, Zip Line | Tags: #ORLawTextbook, #ORRiskManagment, #OutdoorRecreationRiskManagementInsurance&Law, #OutdoorRecreationTextbook, @SagamorePub, Accidents, Angry Guest, Dealing with Claims, General Liability Insurance, Guide, http://www.rec-law.us/ORLawTextbook, Injured Guest, Insurance policy, James H. Moss J.D., Jim Moss, Liability insurance, OR Textbook, Outdoor Recreation Insurance, Outdoor Recreation Law, Outdoor Recreation Risk Management, Outfitter, RecreationLaw, Risk Management, risk management plan, Textbook, Understanding, Understanding Insurance, Understanding Risk Management, Upset Guest Leave a comment These and many other questions are answered in my book Outdoor Recreation Risk Management, Insurance and Law.

These and many other questions are answered in my book Outdoor Recreation Risk Management, Insurance and Law.

Releases, (or as some people incorrectly call them waivers) are a legal agreement that in advance of any possible injury identifies who will pay for what. Releases can and to stop lawsuits.

This book will explain releases and other defenses you can use to put yourself in a position to stop lawsuits and claims.

This book can help you understand why people sue and how you can and should deal with injured, angry or upset guests of your business.

This book is designed to help you rest easy about what you need to do and  how to do it. More importantly, this book will make sure you keep your business afloat and moving forward.

how to do it. More importantly, this book will make sure you keep your business afloat and moving forward.

You did not get into the outdoor recreation business to worry or spend nights staying awake. Get prepared and learn how and why so you can sleep and quit worrying.

Table of Contents

Chapter 1 Outdoor Recreation Risk Management, Law, and Insurance: An Overview

Chapter 2 U.S. Legal System and Legal Research

Chapter 3 Risk 25

Chapter 4 Risk, Accidents, and Litigation: Why People Sue

Chapter 5 Law 57

Chapter 6 Statutes that Affect Outdoor Recreation

Chapter 7 Pre-injury Contracts to Prevent Litigation: Releases

Chapter 8 Defenses to Claims

Chapter 9 Minors

Chapter 10 Skiing and Ski Areas

Chapter 11 Other Commercial Recreational Activities

Chapter 12 Water Sports, Paddlesports, and water-based activities

Chapter 13 Rental Programs

Chapter 14 Insurance

$130.00 plus shipping

Artwork by Don Long donaldoelong@earthlink.net

What went wrong and how to beat the lawsuit when a guide sues to recover fees, he paid to climb mountain Everest after the trip was cancelled? Several things.

Posted: October 16, 2020 Filed under: Climbing, Contract, Mountaineering, Release (pre-injury contract not to sue) | Tags: Cancellation, Cowboy Up, Everest, Garrett Madison, Lawsuit, Mt. Everest, Refund, Release, Zac Bookman 2 CommentsThe client was not properly educated pre-trip, and the paperwork did not cover the right issues and/or say the right things.

All over the news, this past ten days is a story about a lawsuit by a Mt. Everest commercial client who is suing his guide service for a refund when the trip was canceled. After arriving in base camp, the trip was canceled because the Khumbu Icefall had a 15 story serac over hanging the route. The outfitter and the other clients decided to bail because of the risk.

I’m even quoted in one article in Outside Magazine.

A Tech CEO Suing His Guide Could Change Everest Travel

CEO Sues Climbing Guide – Could Set a Terrible Precedent for the Travel Industry

It is not the first time that I’ve heard or been involved in these types’ lawsuits. I knew of one from 20+ years ago where the threatened lawsuit was over a refund because the client did not summit Mt. Everest. I never heard what the outcome was.

One of my clients was threatened with a similar lawsuit. The client wanted his money back because he did not summit. I responded to the client’s demand letter listing every Everest summiteers I knew who would testify about the chances of submitting. I never heard anything else.

These refund attempts happen on mountains all over the world.

Usually these start with a guide service needing clients to stay alive or making a profit or not investigating the client thoroughly. When a climbing guide is broke, they have a tendency to say anything to get money in the door or take anyone. Worse are the ones that can right a check without hesitation or who come with a “climbing resume” but only with guide services.

Climbing with a guide is awesome, but the guide makes all the decisions, no matter what the agreement says and how the issue is phrased and the client never engages his brain or understands how decisions are made when climbing a mountain.

Everyone once in a while it is the client who is trying to save face with his friends and neighbors because he did not summit. Getting his money back proves it was not his fault, that he did not summit.

The next step in the process is education. Clients need to learn two things from the start.

- Their chances of summiting are slim or low based on the mountain.

- The money they pay to summit is spent way before the client ever sets foot in the country where he is climbing.

No matter the mountain your chances of summiting are based on a lot of factors.

- The mountain

-

The guide service

- What the guide service does to get you off the mountain before you can summit

- What the guide service does to get you off the mountain before you can summit

The mountain is obvious, how many days in what conditions and can you survive.

At the same time, there are unscrupulous guide services.

Guide services have been playing games with clients for decades. One game that used to be played on Denali was running the client up the mountain before the client could acclimatize and getting the client sick. This was obvious when you looked at the schedule. There was never enough time between the next load of clients landing on the glacier to acclimatize and summit before the guide had another group to lead.

A different game is still being played on Kilimanjaro. No one tells clients that the hike through the jungle to the base camp is going to leave them and their gear soaking wet. I’ve heard of trips were every single client spent the first two nights shivering in wet sleeping bags before giving up and heading home. No one says to use a waterproof stuff sack or a garbage bag to protect your gear, so thousands each year get to the base of the mountain and turn around.

I’ve not heard of Everest guide services playing any of these games. I do know that your chances of summiting and living are higher based on the amount of money you pay. The past ten years, most of the fatalities have come from guide services that are locally run and very inexpensive compared to everyone else.

I also have only heard great things from the defendant in this case, Garret Madison.

The money paid is gone before you arrive.

Think about the food you will be eating on Mt. Everest. It is purchased in the US, packed for transportation to Katmandu, repacked for shipping to basecamp and repacked for carrying up the mountain. The cost of shipping and packing far outweighs the cost of the food. All of this is done before a US client leaves the US.

Airline tickets, hotel rooms and transportation inside Nepal are paid for in advance. Local guides are hired and paid for, or they find someone different to work for. Competition on Mt. Everest is stiff, so there are plenty of job opportunities for all aspects of getting to basecamp and who you will be climbing with.

Gear is always brought back to the US, cleaned, checked, replaced and then shipped back to Nepal, or used on other mountains in between seasons.

Most of the money you pay to climb a mountain is spent before you leave the US. There are no refunds for food shipped to basecamp, there are no refunds if you can’t summit. I would guess if you wanted some of your money back you can take thirty days of dehydrated food back home with you……. Most is given to the locals and the Sherpa who live on it.

The best way to stop any lawsuit is education and paperwork.

The agreement between the guide and the client must have the following.

- The guide is in command, makes mistakes but is in control. Decisions made by the guide are final yet you are in control of your life. You can ignore them at your own risk.

- You can’t sue and if you do, you will owe me money for breach of the covenants that go with this contract.

- If you do sue, you have to sue me in my little home town a long way from where you live.

- You must purchase travel insurance to protect your investment because I’m not going to.

The guide from the articles might have screwed up. To get the client off their back, he might have said something about a refund. The guide also did not do a good job of explaining with the other clients who were leaving what was going on and why. The plaintiff client was left out of the conversation.

However, climbing Everest is not a guaranty, and no guide will ever bet on who will summit and who will not because the odds are stacked and change constantly.

Worse, it is obvious that this plaintiff thinks his luck is pretty good or the amount of money he paid is too much to lose, e way he puts little value on his life.

Guide says to go home, too dangerous! my response is get out of my way!

Do Something

If you want to climb big mountains and intend to hire a guide to do so.

- Get in shape

- Learn how to climb and climb well. If you can’t run up your local mountains without fear or concern, don’t leave them.

- Go climb big mountains with and without guides. Learn how to make decisions and why on when to climb, where to camp, what to do and when to go home.

- Expect to spend a lot of money, go cheap you might never go home.

- Communicate. Make sure all the promises your guide makes are in writing.

- Cowboy up if you can’t get to the top, you probably ignored steps 1-4.

- Your money is gone and will not be coming back.

If you are a guide service.

- Have enough guts to withstand angry clients because you can’t keep them all happy.

- Get good contracts and releases. Get agreements written by an attorney who knows what a mountain is, what making decisions means and has made those decisions and most importantly knows what goes into the agreement and why!

- Understand that marketing makes promises that risk management has to pay for is true. You tell a client, he or she will summit, you better have a way to get their butt to the top, or you will be in court.

- Make sure your insurance covers advertising, and you have a comprehensive policy to cover those lawsuits that arise more than the negligence lawsuits do.

- Tell everyone you cannot guaranty they can get out of basecamp, even get to basecamp, let alone summit.

- Get good contracts and releases!

What do you think? Leave a comment.

Copyright 2020 Recreation Law (720) 334 8529

If you like this let your friends know or post it on FB, Twitter or LinkedIn

Author: Outdoor Recreation Insurance, Risk Management and Law

Facebook Page: Outdoor Recreation & Adventure Travel Law

Email: Rec-law@recreation-law.com

Google+: +Recreation

Twitter: RecreationLaw

Facebook: Rec.Law.Now

Facebook Page: Outdoor Recreation & Adventure Travel Law

Blog:

www.recreation-law.com

Mobile Site: http://m.recreation-law.com

By Recreation Law Rec-law@recreation-law.com James H. Moss

#AdventureTourism, #AdventureTravelLaw, #AdventureTravelLawyer, #AttorneyatLaw, #Backpacking, #BicyclingLaw, #Camps, #ChallengeCourse, #ChallengeCourseLaw, #ChallengeCourseLawyer, #CyclingLaw, #FitnessLaw, #FitnessLawyer, #Hiking, #HumanPowered, #HumanPoweredRecreation, #IceClimbing, #JamesHMoss, #JimMoss, #Law, #Mountaineering, #Negligence, #OutdoorLaw, #OutdoorRecreationLaw, #OutsideLaw, #OutsideLawyer, #RecLaw, #Rec-Law, #RecLawBlog, #Rec-LawBlog, #RecLawyer, #RecreationalLawyer, #RecreationLaw, #RecreationLawBlog, #RecreationLawcom, #Recreation-Lawcom, #Recreation-Law.com, #RiskManagement, #RockClimbing, #RockClimbingLawyer, #RopesCourse, #RopesCourseLawyer, #SkiAreas, #Skiing, #SkiLaw, #Snowboarding, #SummerCamp, #Tourism, #TravelLaw, #YouthCamps, #ZipLineLawyer,

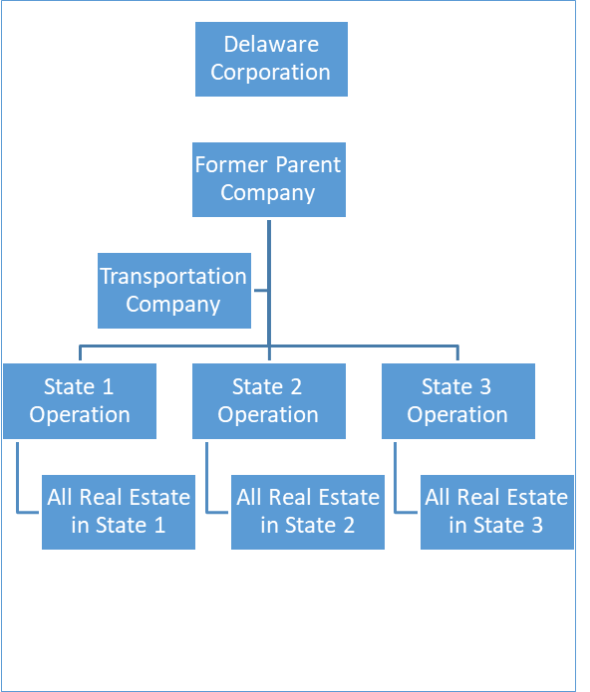

Why would you create more than one Limited Liability Company for your business?

Posted: May 28, 2020 Filed under: Contract | Tags: Delaware, Delaware Corporation, Limited liability company, LLC. Leave a commentThere are dozens of reasons, read on.

There are dozens of reasons why you would create multiple limited liability companies for your business.

- A Limited Liability Company, (LLC), is easy and inexpensive to set up and operate.

- Each LLC protects the assets in it.

- Each LLC protects the assets of the other LLC’s

- Each LLC protects the assets of the parent LLC.

- Each LLC makes it harder to sue the parent and other LLC’s

- Like not having all of your eggs in one basket, separate LLC’s provide better protection for all of your assets.

- If you lose a lawsuit above your insurance limits, only the LLC that was sued is as risk not your other assets, locations or companies.

- Each LLC can be taxed a different way.

- You can take money out of each LLC a different way.

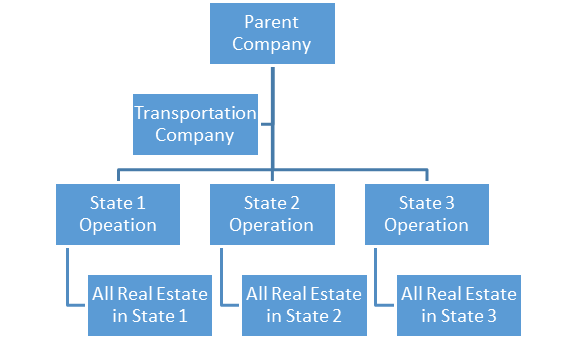

- Setting up different LLC’s for each state you may operate in provides more options for the LLC in that state.

- Setting up a different LLC for each state you operate in provides more tax advantages for the LLC in that state.

- Overall, you create more barriers to losing your business because of creditors.

And there are many more reasons beyond these twelve.

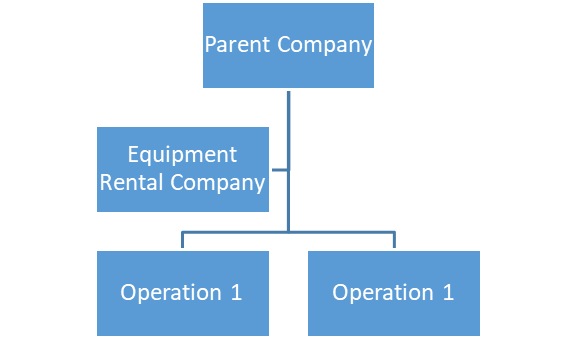

As an example let’s look at a small outfitter or climbing wall with the following assets:

- Two locations (leased)

- Equipment share by both operations

- Equipment at each operation

You would set up the LLC’s this way probably.

Each separate business operation or real estate address should have it’s own LLC. Any equipment that is used by both LLC’s can be in a separate LLC that is rented to the business LLC’s when needed. The equipment rental company can also be used to buy all equipment and products needed by the operations to get better deals. Any management, operations, etc., are done out of the Parent LLC that owns the other three LLCs. If either businesses gets sued, the assets of the other LLC, the joint Equipment and the management assets are protected from that lawsuit.

If you operate a business that is based on permits you may want a separate LLC for each permit you own.

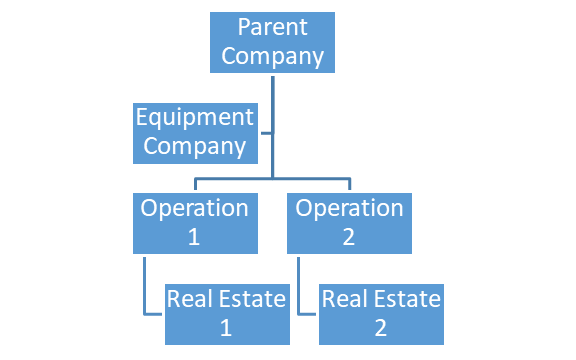

If you owned land under your businesses, you would want those in separate LLC’s. You can lose the business and start the next day because you still own a lot of the equipment and the land.

There are some negative issues with this type of set up.

The relationship between each LLC and the other LLC’s must be in writing with a proper agreement and proper accounting. That means there needs to be a management contract between the parent company and the different LLCs. There needs to be a rental agreement between the equipment company and the operating LLCs.

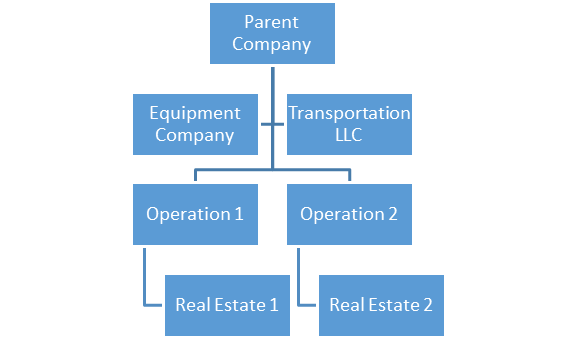

If you are an outfitter with this set up, and you transport your guests in vehicles you would want to add a transportation LLC. Your greatest liability is in moving guests to the activity location. Always keep your liabilities separate from your assets.

In this situation, you would need a lease agreement between the Operations and the Real Estate LLCs.

If you start to grow to the point that this gets unwieldy, you can consolidate and combine assets.

Your situation and growth are going to be different and will vary on how well you, and your CPA can work together. Other than increased accounting costs, you will achieve significant protection from any possible lawsuit by using multiple LLCs with little additional work.

If you have a good CPA, you can also have the LLC’s taxed differently to provide different benefits or income to you. You can take money out of some LLC’s as income, some as rent, others as an independent contractor based on how you initially set them up and how they are recognized by the IRS.

One final idea is you may have assets that are so valuable and small that you do not want to keep them in any LLC that could get sued. An example would be a federal permit or concession contract. You could keep those in your own name or in a different LLC that does nothing but leases those permits to your LLC’s. That way, no matter what, you can start again because you have a valid permit.

The final issue might be if you decided to take your company public someday. Contrary to popular belief, incorporating in Delaware is NOT the place to set up your business. Incorporating in Delaware until you have decided to go public has many negatives.

- People think you are a bigger company, there fore they will sue for more money.

- The cost of incorporating in Delaware is several times more expensive than most other states.

- The yearly costs of maintain a corporation in Delaware is expensive.

- You have to hire a statutory agent in Delaware who adds to your cost.

- You have to follow Delaware law in running your company or corporation.

- Your LLC or Corporation will have to follow Delaware laws so you may have to hire an additional attorney.

What if you want to go public someday? Then at that time, create a Delaware corporation. Have that corporation become the owner of all the other LLCs you have created. Now you are a Delaware corporation ready to go public and have delayed the cost of creating a Delaware corporation until you can afford it.

Save your money when you are starting out, start your LLC in the state where you are going to operate so you understand the state laws your LLC will be operating under.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

Copyright 2020 Recreation Law (720) 334 8529

If you like this let your friends know or post it on FB, Twitter or LinkedIn

Author: Outdoor Recreation Insurance, Risk Management and Law

Facebook Page: Outdoor Recreation & Adventure Travel Law

Email: Rec-law@recreation-law.com

Google+: +Recreation

Twitter: RecreationLaw

Facebook: Rec.Law.Now

Facebook Page: Outdoor Recreation & Adventure Travel Law

Blog:

www.recreation-law.com

Mobile Site: http://m.recreation-law.com

By Recreation Law Rec-law@recreation-law.com James H. Moss

#AdventureTourism, #AdventureTravelLaw, #AdventureTravelLawyer, #AttorneyatLaw, #Backpacking, #BicyclingLaw, #Camps, #ChallengeCourse, #ChallengeCourseLaw, #ChallengeCourseLawyer, #CyclingLaw, #FitnessLaw, #FitnessLawyer, #Hiking, #HumanPowered, #HumanPoweredRecreation, #IceClimbing, #JamesHMoss, #JimMoss, #Law, #Mountaineering, #Negligence, #OutdoorLaw, #OutdoorRecreationLaw, #OutsideLaw, #OutsideLawyer, #RecLaw, #Rec-Law, #RecLawBlog, #Rec-LawBlog, #RecLawyer, #RecreationalLawyer, #RecreationLaw, #RecreationLawBlog, #RecreationLawcom, #Recreation-Lawcom, #Recreation-Law.com, #RiskManagement, #RockClimbing, #RockClimbingLawyer, #RopesCourse, #RopesCourseLawyer, #SkiAreas, #Skiing, #SkiLaw, #Snowboarding, #SummerCamp, #Tourism, #TravelLaw, #YouthCamps, #ZipLineLawyer,

New Book Aids Both CEOs and Students

Posted: August 1, 2019 Filed under: Adventure Travel, Assumption of the Risk, Camping, Challenge or Ropes Course, Climbing, Climbing Wall, Contract, Cycling, Equine Activities (Horses, Donkeys, Mules) & Animals, First Aid, Insurance, Jurisdiction and Venue (Forum Selection), Legal Case, Medical, Mountain Biking, Mountaineering, Paddlesports, Release (pre-injury contract not to sue), Risk Management, Rivers and Waterways, Rock Climbing, Sea Kayaking, Ski Area, Skiing / Snow Boarding, Skydiving, Paragliding, Hang gliding, Swimming, Whitewater Rafting, Zip Line | Tags: Adventure travel, and Law, assumption of the risk, camping, Case Analysis, Challenge or Ropes Course, Climbing, Climbing Wall, Contract, Cycling, Desk Reference, Donkeys, Equine Activities (Horses, first aid, Good Samaritan Statutes, Hang gliding, Insurance, James H. Moss, Jurisdiction and Venue (Forum Selection), Law, Legal Case, Medical, Mountain biking, Mountaineering, Mules) & Animals, Negligence, Outdoor Industry, Outdoor recreation, Outdoor Recreation Insurance, Outdoor Recreation Risk Management, Paddlesports, Paragliding, Recreational Use Statute, Reference Book, Release (pre-injury contract not to sue), Reward, Risk, Risk Management, Rivers and Waterways, Rock climbing, Sea Kayaking, ski area, Ski Area Statutes, Skiing / Snow Boarding, Skydiving, swimming, Textbook, Whitewater Rafting, zip line Leave a comment“Outdoor Recreation Insurance, Risk Management, and Law” is a definitive guide to preventing and overcoming legal issues in the outdoor recreation industry

Outdoor Recreation Insurance, Risk Management, and Law

Denver based James H. Moss, JD, an attorney who specializes in the legal issues of outdoor recreation and adventure travel companies, guides, outfitters, and manufacturers, has written a comprehensive legal guidebook titled, “Outdoor Recreation Insurance, Risk Management, and Law”. Sagamore Publishing, a well-known Illinois-based educational publisher, distributes the book.

Mr. Moss, who applied his 30 years of experience with the legal, insurance, and risk management issues of the outdoor industry, wrote the book in order to fill a void.

“There was nothing out there that looked at case law and applied it to legal problems in outdoor recreation,” Moss explained. “The goal of this book is to provide sound advice based on past law and experience.”

The Reference book is sold via the Summit Magic Publishing, LLC.

While written as a college-level textbook, the guide also serves as a legal primer for executives, managers, and business owners in the field of outdoor recreation. It discusses how to tackle, prevent, and overcome legal issues in all areas of the industry.

The book is organized into 14 chapters that are easily accessed as standalone topics, or read through comprehensively. Specific topics include rental programs, statues that affect outdoor recreation, skiing and ski areas, and defenses to claims. Mr. Moss also incorporated listings of legal definitions, cases, and statutes, making the book easy for laypeople to understand.

PURCHASE

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Table of Cases

Introduction

Outdoor Recreation Law and Insurance: Overview

Risk

Risk

Perception versus Actual Risk

Risk v. Reward

Risk Evaluation

Risk Management Strategies

Humans & Risk

Risk = Accidents

Accidents may/may not lead to litigation

How Do You Deal with Risk?

How Does Acceptance of Risk Convert to Litigation?

Negative Feelings against the Business

Risk, Accidents & Litigation

No Real Acceptance of the Risk

No Money to Pay Injury Bills

No Health Insurance

Insurance Company Subrogation

Negative Feelings

Litigation

Dealing with Different People

Dealing with Victims

Develop a Friend & Eliminate a Lawsuit

Don’t Compound Minor Problems into Major Lawsuits

Emergency Medical Services

Additional Causes of Lawsuits in Outdoor Recreation

Employees

How Do You Handle A Victim?

Dealing with Different People

Dealing with Victims

Legal System in the United States

Courts

State Court System

Federal Court System

Other Court Systems

Laws

Statutes

Parties to a Lawsuit

Attorneys

Trials

Law

Torts

Negligence

Duty

Breach of the Duty

Injury

Proximate Causation

Damages

Determination of Duty Owed

Duty of an Outfitter

Duty of a Guide

Duty of Livery Owner

Duty of Rental Agent

Duty of Volunteer Youth Leader

In Loco Parentis

Intentional Torts

Gross Negligence

Willful & Wanton Negligence

Intentional Negligence

Negligence Per Se

Strict Liability

Attractive Nuisance

Results of Acts That Are More than Ordinary Negligence

Product Liability

Contracts

Breach of Contract

Breach of Warranty

Express Warranty

Implied Warranty

Warranty of Fitness for a Particular Purpose

Warranty of Merchantability

Warranty of Statute

Detrimental Reliance

Unjust Enrichment

Liquor Liability

Food Service Liability

Damages

Compensatory Damages

Special Damages

Punitive Damages

Statutory Defenses

Skier Safety Acts

Whitewater Guides & Outfitters

Equine Liability Acts

Legal Defenses

Assumption of Risk

Express Assumption of Risk

Implied Assumption of Risk

Primary Assumption of Risk

Secondary Assumption of Risk

Contributory Negligence

Assumption of Risk & Minors

Inherent Dangers

Assumption of Risk Documents.

Assumption of Risk as a Defense.

Statutory Assumption of Risk

Express Assumption of Risk

Contributory Negligence

Joint and Several Liability

Release, Waivers & Contracts Not to Sue

Why do you need them

Exculpatory Agreements

Releases

Waivers

Covenants Not to sue

Who should be covered

What should be included

Negligence Clause

Jurisdiction & Venue Clause

Assumption of Risk

Other Clauses

Indemnification

Hold Harmless Agreement

Liquidated Damages

Previous Experience

Misc

Photography release

Video Disclaimer

Drug and/or Alcohol clause

Medical Transportation & Release

HIPAA

Problem Areas

What the Courts do not want to see

Statute of Limitations

Minors

Adults

Defenses Myths

Agreements to Participate

Parental Consent Agreements

Informed Consent Agreements

Certification

Accreditation

Standards, Guidelines & Protocols

License

Specific Occupational Risks

Personal Liability of Instructors, Teachers & Educators

College & University Issues

Animal Operations, Packers

Equine Activities

Canoe Livery Operations

Tube rentals

Downhill Skiing

Ski Rental Programs

Indoor Climbing Walls

Instructional Programs

Mountaineering

Retail Rental Programs

Rock Climbing

Tubing Hills

Whitewater Rafting

Risk Management Plan

Introduction for Risk Management Plans

What Is A Risk Management Plan?

What should be in a Risk Management Plan

Risk Management Plan Template

Ideas on Developing a Risk Management Plan

Preparing your Business for Unknown Disasters

Building Fire & Evacuation

Dealing with an Emergency

Insurance

Theory of Insurance

Insurance Companies

Deductibles

Self-Insured Retention

Personal v. Commercial Policies

Types of Policies

Automobile

Comprehension

Collision

Bodily Injury

Property Damage

Uninsured Motorist

Personal Injury Protection

Non-Owned Automobile

Hired Car

Fire Policy

Coverage

Liability

Named Peril v. All Risk

Commercial Policies

Underwriting

Exclusions

Special Endorsements

Rescue Reimbursement

Policy Procedures

Coverage’s

Agents

Brokers

General Agents

Captive Agents

Types of Policies

Claims Made

Occurrence

Claims

Federal and State Government Insurance Requirements

Bibliography

Index

The 427-page volume is sold via Summit Magic Publishing, LLC.

What is a Risk Management Plan and What do You Need in Yours?

Posted: July 25, 2019 Filed under: Activity / Sport / Recreation, Adventure Travel, Assumption of the Risk, Avalanche, Camping, Challenge or Ropes Course, Climbing, Climbing Wall, Contract, Cycling, Equine Activities (Horses, Donkeys, Mules) & Animals, First Aid, Health Club, Indoor Recreation Center, Jurisdiction and Venue (Forum Selection), Legal Case, Medical, Minors, Youth, Children, Mountain Biking, Mountaineering, Paddlesports, Playground, Racing, Racing, Release (pre-injury contract not to sue), Risk Management, Rivers and Waterways, Rock Climbing, Scuba Diving, Sea Kayaking, Search and Rescue (SAR), Ski Area, Skier v. Skier, Skiing / Snow Boarding, Skydiving, Paragliding, Hang gliding, Snow Tubing, Sports, Summer Camp, Swimming, Triathlon, Whitewater Rafting, Youth Camps, Zip Line | Tags: #ORLawTextbook, #ORRiskManagment, #OutdoorRecreationRiskManagementInsurance&Law, #OutdoorRecreationTextbook, @SagamorePub, Adventure travel, and Law, assumption of the risk, camping, Case Analysis, Challenge or Ropes Course, Climbing, Climbing Wall, Contract, Cycling, Donkeys, Equine Activities (Horses, first aid, General Liability Insurance, Good Samaritan Statutes, Guide, Hang gliding, http://www.rec-law.us/ORLawTextbook, Insurance, Insurance policy, James H. Moss, James H. Moss J.D., Jim Moss, Jurisdiction and Venue (Forum Selection), Legal Case, Liability insurance, Medical, Mountain biking, Mountaineering, Mules) & Animals, Negligence, OR Textbook, Outdoor Recreation Insurance, Outdoor Recreation Law, Outdoor Recreation Risk Management, Outfitter, Paddlesports, Paragliding, Recreational Use Statute, Release (pre-injury contract not to sue), Risk Management, risk management plan, Rivers and Waterways, Rock climbing, Sea Kayaking, ski area, Ski Area Statutes, Skiing / Snow Boarding, Skydiving, swimming, Textbook, Understanding, Understanding Insurance, Understanding Risk Management, Whitewater Rafting, zip line Leave a commentEveryone has told you, that you need a risk management plan. A plan to follow if you have

Outdoor Recreation Insurance, Risk Management, and Law

a crisis. You‘ve seen several and they look burdensome and difficult to write. Need help writing a risk management plan? Need to know what should be in your risk management plan? Need Help?

This book can help you understand and write your plan. This book is designed to help you rest easy about what you need to do and how to do it. More importantly, this book will make sure your plan is a workable plan, not one that will create liability for you.

Table of Contents

Chapter 1 Outdoor Recreation Risk Management, Law, and Insurance: An Overview

Chapter 2 U.S. Legal System and Legal Research

Chapter 3 Risk 25

Chapter 4 Risk, Accidents, and Litigation: Why People Sue

Chapter 5 Law 57

Chapter 6 Statutes that Affect Outdoor Recreation

Chapter 7 PreInjury Contracts to Prevent Litigation: Releases

Chapter 8 Defenses to Claims

Chapter 9 Minors

Chapter 10 Skiing and Ski Areas

Chapter 11 Other Commercial Recreational Activities

Chapter 12 Water Sports, Paddlesports, and water-based activities

Chapter 13 Rental Programs

Chapter 14 Insurance

$130.00 plus shipping

Can’t Sleep? Guest was injured, and you don’t know what to do? This book can answer those questions for you.

Posted: July 23, 2019 Filed under: Adventure Travel, Assumption of the Risk, Avalanche, Camping, Climbing, Climbing Wall, Contract, Criminal Liability, Cycling, Equine Activities (Horses, Donkeys, Mules) & Animals, First Aid, Health Club, How, Indoor Recreation Center, Insurance, Jurisdiction and Venue (Forum Selection), Medical, Minors, Youth, Children, Mountain Biking, Mountaineering, Paddlesports, Playground, Racing, Racing, Release (pre-injury contract not to sue), Risk Management, Rivers and Waterways, Rock Climbing, Scuba Diving, Sea Kayaking, Search and Rescue (SAR), Ski Area, Skier v. Skier, Skiing / Snow Boarding, Skydiving, Paragliding, Hang gliding, Snow Tubing, Sports, Summer Camp, Swimming, Triathlon, Whitewater Rafting, Youth Camps, Zip Line | Tags: #ORLawTextbook, #ORRiskManagment, #OutdoorRecreationRiskManagementInsurance&Law, #OutdoorRecreationTextbook, @SagamorePub, Accidents, Angry Guest, Dealing with Claims, General Liability Insurance, Guide, http://www.rec-law.us/ORLawTextbook, Injured Guest, Insurance policy, James H. Moss J.D., Jim Moss, Liability insurance, OR Textbook, Outdoor Recreation Insurance, Outdoor Recreation Law, Outdoor Recreation Risk Management, Outfitter, RecreationLaw, Risk Management, risk management plan, Textbook, Understanding, Understanding Insurance, Understanding Risk Management, Upset Guest Leave a comment An injured guest is everyone’s business owner’s nightmare. What happened, how do you make sure it does not happen again, what can you do to help the guest, can you help the guests are just some of the questions that might be keeping you up at night.

An injured guest is everyone’s business owner’s nightmare. What happened, how do you make sure it does not happen again, what can you do to help the guest, can you help the guests are just some of the questions that might be keeping you up at night.

This book can help you understand why people sue and how you can and should deal with injured, angry or upset guests of your business.

This book is designed to help you rest easy about what you need to do and how to do it. More importantly, this book will make sure you keep your business afloat and moving forward.

You did not get into the outdoor recreation business to worry or spend nights staying awake. Get prepared and learn how and why so you can sleep and quit worrying.

Table of Contents

Chapter 1 Outdoor Recreation Risk Management, Law, and Insurance: An Overview

Chapter 2 U.S. Legal System and Legal Research

Chapter 3 Risk 25

Chapter 4 Risk, Accidents, and Litigation: Why People Sue

Chapter 5 Law 57

Chapter 6 Statutes that Affect Outdoor Recreation

Chapter 7 Pre-injury Contracts to Prevent Litigation: Releases

Chapter 8 Defenses to Claims

Chapter 9 Minors

Chapter 10 Skiing and Ski Areas

Chapter 11 Other Commercial Recreational Activities

Chapter 12 Water Sports, Paddlesports, and water-based activities

Chapter 13 Rental Programs

Chapter 14 Insurance

$130.00 plus shipping

Need a Handy Reference Guide to Understand your Insurance Policy?

Posted: July 18, 2019 Filed under: Adventure Travel, Assumption of the Risk, Avalanche, Challenge or Ropes Course, Climbing, Contract, Cycling, Equine Activities (Horses, Donkeys, Mules) & Animals, Health Club, Indoor Recreation Center, Insurance, Jurisdiction and Venue (Forum Selection), Minors, Youth, Children, Mountain Biking, Mountaineering, Paddlesports, Racing, Release (pre-injury contract not to sue), Risk Management, Rivers and Waterways, Rock Climbing, Scuba Diving, Sea Kayaking, Ski Area, Skier v. Skier, Skiing / Snow Boarding, Skydiving, Paragliding, Hang gliding, Snow Tubing, Sports, Summer Camp, Swimming, Whitewater Rafting, Youth Camps, Zip Line | Tags: #ORLawTextbook, #ORRiskManagment, #OutdoorRecreationRiskManagementInsurance&Law, #OutdoorRecreationTextbook, @SagamorePub, Adventure travel, and Law, assumption of the risk, camping, Case Analysis, Challenge or Ropes Course, Climbing, Climbing Wall, Contract, Cycling, Donkeys, Equine Activities (Horses, first aid, General Liability Insurance, Good Samaritan Statutes, Guide, Hang gliding, http://www.rec-law.us/ORLawTextbook, Insurance, Insurance policy, James H. Moss, James H. Moss J.D., Jim Moss, Jurisdiction and Venue (Forum Selection), Legal Case, Liability insurance, Medical, Mountain biking, Mountaineering, Mules) & Animals, Negligence, Outdoor Recreation Insurance, Outdoor Recreation Law, Outdoor Recreation Risk Management, Outfitter, Paddlesports, Paragliding, Recreational Use Statute, Release (pre-injury contract not to sue), Risk Management, Rivers and Waterways, Rock climbing, Sea Kayaking, ski area, Ski Area Statutes, Skiing / Snow Boarding, Skydiving, swimming, Whitewater Rafting, zip line Leave a commentThis book should be on every outfitter and guide’s desk. It will answer your questions, help you sleep at night, help you answer your guests’ questions and allow you to run your business with less worry.

Table of Contents

Chapter 1 Outdoor Recreation Risk Management, Law, and Insurance: An Overview

Chapter 2 U.S. Legal System and Legal Research

Chapter 3 Risk 25

Chapter 4 Risk, Accidents, and Litigation: Why People Sue

Chapter 5 Law 57

Chapter 6 Statutes that Affect Outdoor Recreation

Chapter 7 PreInjury Contracts to Prevent Litigation: Releases

Chapter 8 Defenses to Claims

Chapter 9 Minors

Chapter 10 Skiing and Ski Areas

Chapter 11 Other Commercial Recreational Activities

Chapter 12 Water Sports, Paddlesports, and water-based activities

Chapter 13 Rental Programs

Chapter 14 Insurance

$99.00 plus shipping

You can collect for damaged gear you rented to customers if your agreements are correct. This snowmobile outfitter recovered $27,000 for $220.11 in damages.

Posted: May 13, 2019 Filed under: Colorado, Contract, Release (pre-injury contract not to sue) | Tags: admissible, attorneys' fees, cases, collection, collector, credit card, debt collection, debt collector, demand letter, demand letters, discovery, disputed, documents, Email, engaging, entity, genuine, law firm, letters, machine, matters, missing, Mountain Law Group, nonmoving, nonmoving party, opposing, owed, parties, practice of law, preface, principal purpose, regularity, regularly, Rental, Rental Agreement, ride, signature, Snowmobile, Summary judgment, summary judgment motion 1 CommentIt helps to get that much money if the customer is a jerk and tries to get out of what they owe you. It makes the final judgment even better when one of the plaintiffs is an attorney.

Citation: Hightower-Henne v. Gelman, 2012 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 4514, 2012 WL 95208

State: Colorado; United States District Court for the District of Colorado

Plaintiff: Tracy L. Hightower-Henne, and Thomas Henne

Defendant: Leonard M. Gelman

Plaintiff Claims: Violation of the Fair Debt Collections Act

Defendant Defenses: They did not violate the act

Holding: For the Defendant

Year: 2012

Summary

The plaintiff’s in this case rented snowmobiles and brought one back damaged. The release they signed to rent the snowmobiles stated if they damaged the snowmobiles they would have to pay for the damage and any lost time the snowmobiles could not be rented (like a car rental agreement).

The plaintiffs damaged a snowmobile and agreed to pay for the damages. The Snowmobile outfitter agreed not to charge them for the lost rental income.

When the plaintiff’s got home, they denied the claim on their credit card bill. The Snowmobile outfitter sued them for the $220.11 in damages and received a judgment of $27,000.

The plaintiff then sued the attorney representing the snowmobile outfitter for violation of the federal Fair Debt Collection’s act, which is the subject of this lawsuit. The plaintiff lost that lawsuit also.

This case shows how agreements in advance to pay for damages from rented equipment are viable and can be upheld if used.

Facts

Although this is described as a debt collection case, it is a case where an outfitter can recover for the damages done to the equipment that he rented to the plaintiffs. The facts are from this case, which took them from an underlying County Court decision in Summit County Colorado.

Mrs. Hightower-Henne, a Nebraska attorney, rented two snowmobiles from Colorado Backcountry Rentals (“CBR”) for herself and her husband, signing the rental agreement for the two machines and declining the offered insurance to cover loss or damage to the machines while in their possession. While at the CBR’s office, the Hennes were shown a video depicting proper operation of snowmobiles in general and were also verbally advised on snowmobile use by an employee of CBR. Plaintiffs, a short while thereafter, met another employee of CBR, Mr. Weber, at Vail Pass and were given possession of the snowmobiles after an opportunity to inspect the machines. Plaintiffs utilized their entire allotted time on the snowmobiles and brought them back to Mr. Weber as planned. Mr. Weber immediately noticed that the snowmobile ridden by Mr. Henne was missing its air box cover and faring, described as a large blue shield on the front of the snowmobile, entirely visible to any driver. At the he returned the snowmobile, Mr. Henne told Mr. Weber that the parts had fallen off approximately two hours into the ride and that he had tried to carry the faring back, but, as he was unable to do so, he left the part on the trail.3 Mr. Henne signed a form acknowledging the missing part(s) and produced his driver’s license and a credit card with full intent that charges to fix the snowmobile would be levied against that card. Mr. Henne signed a blank credit card slip, which the parties all understood would be filled-in once the damage could be definitively ascertained.4 Although CBR, pursuant to the rental agreement signed by Mrs. Hightower-Henne, was entitled to charge the Hennes for loss of rentals for the snowmobile while it was being repaired, CBR waived that fee and charged Mr. Henne a total of only $220.11.

…one of the rented snowmobiles suffered damage while in the possession of Mr. Henne. Although agreeing to pay for the damage initially, Mr. Henne later disputed the charges levied by CBR against his credit card, resulting in a collection lawsuit brought by CBR against Mr. and Mrs. Henne in Summit County Court. This court takes the underlying facts from the Judgment Order of Hon. Wayne Patton in the Summit County Case as Judge Patton presided over a trial and therefore had the best opportunity to assess the witnesses, including their credibility and analyze the exhibits. The defendant in this case, Leonard M. Gelman, was the attorney for CBR in the Summit County case.

This story changed at trial in the Summit County case, where Mr. Henne reported that the parts fell off the machine about 5-10 minutes into the ride. Mr. Henne also testified that he did not know he was missing a part – he claimed a group of strangers told him that his snowmobile was missing a part and he thereafter retraced his route to try to find the piece but could not find it. Judge Patton found that “Mr. Henne’s testimony does not make sense to the court.” The court found that the evidence indicated the parts came off during the ride and that since the clips that held the part on were broken and the “intake silencer” was cracked, Judge Patton indicated, “The court does not believe that the fairing just fell off.”

Mr. Henne’s proffered credit card was for a different account that Mrs. Hightower-Henne had used to rent the snowmobiles.

CBR’s notation on the Estimated Damages form states, “Will not charge customer for the 2 days loss rents as good will.”

At trial in the Summit County case, Mr. and Mrs. Henne maintained that Mr. Henne’s sig-nature on the damage estimate and the credit card slip were forgeries. The court found that Mr. Weber, CBR’s employee who witnessed Mr. Henne sign the documents, was a credible witness and found Mr. Henne’s claim that he had not signed the documents was not credible. The court also found that there was no incentive whatsoever for anyone to have forged Mr. Henne’s signature on anything since “[CBR] already had Ms. Hightower-Henne’s credit card information and authorization so even if Mr. Henne had refused to sign the disputed documents it had recourse without having to resort to subterfuge.”

After deciding in favor of CBR on the liability of Mr. and Mrs. Henne for the damage to the snowmobile in the total amount of $653.60, Judge Patton considered the issue of attorney’s fees and costs incurred in that proceeding. Finding that the original rental documents signed by Mrs. Hightower-Henne contained a prevailing party award of attorney fees pro-vision, the court awarded CBR $25,052.50 in attorney’s fees against Mrs. Hightower-Henne plus $1,737.92 in costs.6 The court stated that even though the attorney fee award was substantial considering the amount of the original debt, the time expended by CBR’s counsel was greatly exacerbated by Mrs. Hightower-Henne’s “motions and threats” and that it was the Hennes who “created the need for [considerable] hours by their actions in filing baseless criminal complaints, filing motions to continue the trial and by seeking to have phone testimony of several witnesses who had no knowledge of what took place while Defendant’s (sic) had possession of the snowmobiles.”

As a result of groundless criminal claims, baseless counterclaims, perjured testimony and over-zealous defense, instead of owing $220.11 for the snowmobile’s missing part, after the dust settled on the Summit County case, the Hennes became responsible for a judgment in excess of $27,000.00.

Analysis: making sense of the law based on these facts.

The facts set forth in the underlying damage recovery case, are the important part. In this case, the attorney for the snowmobile outfitter was found not to have violated the federal Fair Debt Collections Act.

In awarding judgment to the defendant in this case, the judge also awarded him costs.

Defendant Leonard M. Gelman’s Motion for Summary Judgment is GRANTED and this case is dismissed with prejudice. Defendant may have his cost by filing a bill of costs pursuant to D.C.COLO.LCivR 54.1 and the Clerk of Court shall enter final judgment in favor of Defendant Gelman in accordance with this Order.

Adding insult to injury. Sometimes it be better to quit while you are behind.

| Jim Moss is an attorney specializing in the legal issues of the outdoor recreation community. He represents guides, guide services, outfitters both as businesses and individuals and the products they use for their business. He has defended Mt. Everest guide services, summer camps, climbing rope manufacturers, avalanche beacon manufacturers, and many more manufacturers and outdoor industries. Contact Jim at Jim@Rec-Law.us |

Jim is the author or co-author of six books about the legal issues in the outdoor recreation world; the latest is Outdoor Recreation Insurance, Risk Management

To see Jim’s complete bio go here and to see his CV you can find it here. To find out the purpose of this website go here.

G-YQ06K3L262

What do you think? Leave a comment.

If you like this let your friends know or post it on FB, Twitter or LinkedIn

Author: Outdoor Recreation Insurance, Risk Management and Law

Facebook Page: Outdoor Recreation & Adventure Travel Law

Email: Jim@Rec-Law.US

By Recreation Law Rec-law@recreation-law.com James H. Moss

@2024 Summit Magic Publishing, LLC

#AdventureTourism, #AdventureTravelLaw, #AdventureTravelLawyer, #AttorneyatLaw, #Backpacking, #BicyclingLaw, #Camps, #ChallengeCourse, #ChallengeCourseLaw, #ChallengeCourseLawyer, #CyclingLaw, #FitnessLaw, #FitnessLawyer, #Hiking, #HumanPowered, #HumanPoweredRecreation, #IceClimbing, #JamesHMoss, #JimMoss, #Law, #Mountaineering, #Negligence, #OutdoorLaw, #OutdoorRecreationLaw, #OutsideLaw, #OutsideLawyer, #RecLaw, #Rec-Law, #RecLawBlog, #Rec-LawBlog, #RecLawyer, #RecreationalLawyer, #RecreationLaw, #RecreationLawBlog, #RecreationLawcom, #Recreation-Lawcom, #Recreation-Law.com, #RiskManagement, #RockClimbing, #RockClimbingLawyer, #RopesCourse, #RopesCourseLawyer, #SkiAreas, #Skiing, #SkiLaw, #Snowboarding, #SummerCamp, #Tourism, #TravelLaw, #YouthCamps, #ZipLineLawyer, #RecreationLaw, #OutdoorLaw, #OutdoorRecreationLaw, #SkiLaw,

Hightower-Henne v. Gelman, 2012 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 4514

Posted: May 1, 2019 Filed under: Colorado, Contract, Legal Case, Release (pre-injury contract not to sue) | Tags: admissible, attorneys' fees, collection, collector, credit card, demand letters, discovery, disputed, Email, engaging, entity, genuine, law firm, machine, missing, Mountain Law Group, nonmoving party, opposing, owed, practice of law, preface, principal purpose, regularity, regularly, Rental, rental agree-ment, ride, signature, Snowmobile, Summary judgment Leave a commentTo Read an Analysis of this decision see: You can collect for damaged gear you rented to customers if your agreements are correct. This snowmobile outfitter recovered $27,000 for $220.11 in damages.

Hightower-Henne v. Gelman, 2012 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 4514

Tracy L. Hightower-Henne, and Thomas Henne, Plaintiffs, v. Leonard M. Gelman, Defendant.

Civil Action No. 11-cv-01114-KMT-BNB

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLORADO

2012 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 4514

January 12, 2012, Decided

January 12, 2012, Filed

CORE TERMS: collection, collector, snowmobile, summary judgment, discovery, credit card, rental, Mountain Law Group, demand letters, email, entity, law firm, preface, missing, nonmoving party, principal purpose, regularity, regularly, disputed, opposing, genuine, rental agreement, signature, machine, ride, admissible, engaging, owed, practice of law, attorney’s fees

COUNSEL: [*1] For Tracy L. Hightower-Henne, Thomas J. Henne, Plaintiffs: Daniel Teodoru, Erin Colleen Hunter, West Brown Huntley & Hunter, P.C., Breckenridge, CO.

For Leonard M. Gelman, Defendant: Rusty David Miller, Thomas Neville Alfrey, Treece Alfrey Musat, P.C., Denver, CO.

JUDGES: Kathleen M. Tafoya, United States Magistrate Judge.

OPINION BY: Kathleen M. Tafoya

OPINION

ORDER

This matter is before the court on Defendant Leonard M. Gelman’s Motion for Summary Judgment [Doc. No. 17] (“Mot.”) filed August 12, 2011. Plaintiffs, Tracy Hightower-Henne and Thomas Henne (collectively “the Hennes”), responded on September 14, 2011 [Doc. No. 23] (“Resp.”) and the defendant filed a Reply on October 3, 2011 [Doc. No. 25]. Also considered is Plaintiffs’ “Motion to File Sur-Reply” [Doc. No. 26], which is denied.1

1 Neither the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure nor the Local Rules of Practice in the District of Colorado provide for the filing of a surreply. Additionally, the court’s review of the proposed surreply reveals it is nothing more than an attempted unauthorized additional bite at the proverbial apple and adds nothing of merit to the summary judgment analysis.

Background

On February 8, 2010, Nebraska residents Tracy L. Hightower-Henne [*2] and her husband Thomas Henne joined a small group of friends and family for a snowmobile ride in Vail, Colorado. Mrs. Hightower-Henne, a Nebraska attorney, rented two snowmobiles from Colorado Backcountry Rentals (“CBR”) for herself and her husband, signing the rental agreement for the two machines and declining the offered insurance to cover loss or damage to the machines while in their possession. (Mot., Ex. H, Judgment Order of County Court Judge Wayne Patton, April 21, 2011, hereinafter “Judgment Order” at 1.)2 While at the CBR’s office, the Hennes were shown a video depicting proper operation of snowmobiles in general and were also verbally advised on snowmobile use by an employee of CBR. (Id.) Plaintiffs, a short while thereafter, met another employee of CBR, Mr. Weber, at Vail Pass and were given possession of the snowmobiles after an opportunity to inspect the machines. (Id. at 2.) Plaintiffs utilized their entire allotted time on the snowmobiles and brought them back to Mr. Weber as planned. Mr. Weber immediately noticed that the snowmobile ridden by Mr. Henne was missing its air box cover and faring, described as a large blue shield on the front of the snowmobile, entirely [*3] visible to any driver. (Id. at 3.) At the he returned the snowmobile, Mr. Henne told Mr. Weber that the parts had fallen off approximately two hours into the ride and that he had tried to carry the faring back, but, as he was unable to do so, he left the part on the trail.3 (Id. at 2.) Mr. Henne signed a form acknowledging the missing part(s) and produced his driver’s license and a credit card with full intent that charges to fix the snowmobile would be levied against that card. Mr. Henne signed a blank credit card slip, which the parties all understood would be filled-in once the damage could be definitively ascertained.4 (Id.) Although CBR, pursuant to the rental agreement signed by Mrs. Hightower-Henne, was entitled to charge the Hennes for loss of rentals for the snowmobile while it was being repaired, CBR waived that fee5 and charged Mr. Henne oa total of only $220.11. (Mot., Ex. B.)

2 As will be discussed in more detail herein, one of the rented snowmobiles suffered damage while in the possession of Mr. Henne. Although agreeing to pay for the damage initially, Mr. Henne later disputed the charges levied by CBR against his credit card, resulting in a collection lawsuit brought by [*4] CBR against Mr. and Mrs. Henne in Summit County Court, Case Number 10 C 255 ). (See Mot., Ex. G; hereinafter, the “Summit County case.”) This court takes the underlying facts from the Judgment Order of Hon. Wayne Patton in the Summit County Case as Judge Patton presided over a trial and therefore had the best opportunity to assess the witnesses, including their credibility and analyze the exhibits. The defendant in this case, Leonard M. Gelman, was the attorney for CBR in the Summit County case.

3 This story changed at trial in the Summit County case, where Mr. Henne reported that the parts fell off the machine about 5-10 minutes into the ride. Mr. Henne also testified that he did not know he was missing a part – he claimed a group of strangers told him that his snowmobile was missing a part and he thereafter retraced his route to try to find the piece but could not find it. Judge Patton found that “Mr. Henne’s testimony does not make sense to the court.” (Judgment Order at 3.) The court found that the evidence indicated the parts came off during the ride and that since the clips that held the part on were broken and the “intake silencer” was cracked, Judge Patton indicated, “The court [*5] does not believe that the fairing just fell off.” (Id.)

4 Mr. Henne’s proffered credit card was for a different account that Mrs. Hightower-Henne had used to rent the snowmobiles.

5 CBR’s notation on the Estimated Damages form states, “Will not charge customer for the 2 days loss rents as good will.” (Mot., Ex. B.)

Upon their return to Nebraska, however, Mr. and Mrs. Henne apparently decided they did not want to pay for the damage to the snowmobile, even with the waiver of the rental loss, and contested the charge to Mr. Henne’s credit card resulting in a reversal of the charge by the credit card issuer. Further, the Hennes leveled criminal forgery accusations against CBR’s employee with the Frisco, Colorado Police Department (id. at 4), alleging that the acknowledgment of damage form and the credit card slip were not signed by Mr. Henne. The police department investigated, but no charges were filed.

Mr. Henne’s ultimate cancellation of his former acquiescence to payment caused CBR to contact their corporate lawyer, Defendant Gelman, and ask that he attempt to obtain payment from the Hennes, authorizing a law suit if initial requests for payment failed. Obviously, CBR was no longer willing [*6] to waive the fee for loss of rental which was part of the contract Mrs. Hightower-Henne signed. (Id. at 2.)

At trial in the Summit County case, Mr. and Mrs. Henne maintained that Mr. Henne’s signature on the damage estimate and the credit card slip were forgeries. (Id. at 4.) The court found that Mr. Weber, CBR’s employee who witnessed Mr. Henne sign the documents, was a credible witness and found Mr. Henne’s claim that he had not signed the documents was not credible. (Id.) The court also found that there was no incentive whatsoever for anyone to have forged Mr. Henne’s signature on anything since “[CBR] already had Ms. Hightower-Henne’s credit card information and authorization so even if Mr. Henne had refused to sign the disputed documents it had recourse without having to resort to subterfuge.” (Id.)

After deciding in favor of CBR on the liability of Mr. and Mrs. Henne for the damage to the snowmobile in the total amount of $653.60, Judge Patton considered the issue of attorney’s fees and costs incurred in that proceeding. Finding that the original rental documents signed by Mrs. Hightower-Henne contained a prevailing party award of attorney fees provision, the court awarded CBR [*7] $25,052.50 in attorney’s fees against Mrs. Hightower-Henne plus $1,737.92 in costs.6 The court stated that even though the attorney fee award was substantial considering the amount of the original debt, the time expended by CBR’s counsel was greatly exacerbated by Mrs. Hightower-Henne’s “motions and threats” and that it was the Hennes who “created the need for [considerable] hours by their actions in filing baseless criminal complaints, filing motions to continue the trial and by seeking to have phone testimony of several witnesses who had no knowledge of what took place while Defendant’s (sic) had possession of the snowmobiles.” (Mot., Ex. I, June 22, 2011 Order of Hon. Wayne Patton, hereinafter “Atty. Fee Order” at 3.) The court also found that “although this was a case akin to a small claims case, Mrs. Hightower-Henne defended the case as if it were complex litigation.”7 (Id. at 1.) Judge Patton stated, with respect to the counterclaim filed by the Hennes, that “[a]lthough Mrs. Hightower-Henne did not pursue that claim at trial it shows the lengths she was willing to go to avoid payment of what was a fairly small claim.” (Id. at 1.)

6 Costs were awarded against both Mr. and Mrs. Henne [*8] jointly and severally.

7 In December 2010, the Hennes hired outside counsel to defend them in the county court action. (Id. at 4.)

As a result of groundless criminal claims, baseless counterclaims, perjured testimony and over-zealous defense, instead of owing $220.11 for the snowmobile’s missing part, after the dust settled on the Summit County case, the Hennes became responsible for a judgment in excess of $27,000.00.

In a prodigiously perfect example of throwing good money after bad, the Hennes now continue to prosecute this federal action against the lawyer representing CBR in the Summit County case, alleging violations of the federal Fair Debt Collection Practices Act (“FDCPA”).8 Unfortunately, even though the issue was raised at some point in the county court case, (see id. at 3, “Mrs. Hightower-Henne also made allegations that Plaintiff was violating fair debt collection laws”), these particular allegations were not resolved by the county court. Therefore, this court is now compelled to reluctantly follow the Hennes down this white rabbit’s hole to resolve the federal case.

8 This case was originally filed against CBR’s lawyer by the Hennes in Summit County on March 31, 2011, suspiciously [*9] a mere one week before commencing trial on the underlying case before Judge Patton. Defendant Gelman removed the case to federal court post-trial on April 27, 2011, one week subsequent to Judge Patton’s ruling against the Hennes. Between April 27, 2011 and August 12, 2011, the Hennes could have revisited the wisdom of continuing with this case had they been so inclined. However, the Hennes have not sought to even amend their Complaint in this matter, even though the findings call into question many of the arguments embodied in the federal complaint. (See, e.g., Compl. ¶ 26.)

Analysis

A. Legal Standard

Summary judgment is appropriate if “the movant shows that there is no genuine dispute as to any material fact and the movant is entitled to judgment as a matter of law.” Fed. R. Civ. P. 56(a). The moving party bears the initial burden of showing an absence of evidence to support the nonmoving party’s case. Celotex Corp. v. Catrett, 477 U.S. 317, 325, 106 S. Ct. 2548, 91 L. Ed. 2d 265 (1986). “Once the moving party meets this burden, the burden shifts to the nonmoving party to demonstrate a genuine issue for trial on a material matter.” Concrete Works, Inc. v. City & County of Denver, 36 F.3d 1513, 1518 (10th Cir. 1994) (citing [*10] Celotex, 477 U.S. at 325). The nonmoving party may not rest solely on the allegations in the pleadings, but must instead designate “specific facts showing that there is a genuine issue for trial.” Celotex, 477 U.S. at 324; see also Fed. R. Civ. P. 56(c). A disputed fact is “material” if “under the substantive law it is essential to the proper disposition of the claim.” Adler v. Wal-Mart Stores, Inc., 144 F.3d 664, 670 (10th Cir.1998) (citing Anderson v. Liberty Lobby, Inc., 477 U.S. 242, 248, 106 S. Ct. 2505, 91 L. Ed. 2d 202 (1986)). A dispute is “genuine” if the evidence is such that it might lead a reasonable jury to return a verdict for the nonmoving party. Thomas v. Metropolitan Life Ins. Co., 631 F.3d 1153, 1160 (10th Cir. 2011) (citing Anderson, 477 U.S. at 248).

When ruling on a motion for summary judgment, a court may consider only admissible evidence. See Johnson v. Weld County, Colo., 594 F.3d 1202, 1209-10 (10th Cir. 2010). The factual record and reasonable inferences therefrom are viewed in the light most favorable to the party opposing summary judgment. Concrete Works, 36 F.3d at 1517. At the summary judgment stage of litigation, a plaintiff’s version of the facts must find support in the record. Thomson v. Salt Lake Cnty., 584 F.3d 1304, 1312 (10th Cir. 2009). [*11] “When opposing parties tell two different stories, one of which is blatantly contradicted by the record, so that no reasonable jury could believe it, a court should not adopt that version of the facts for purposes of ruling on a motion for summary judgment.” Scott v. Harris, 550 U.S. 372, 380, 127 S. Ct. 1769, 167 L. Ed. 2d 686 (2007); Thomson, 584 F.3d at 1312.

B. Request for Additional Discovery

As an initial matter, Plaintiffs request the court grant them further discovery in order to fully explore the matters raised by Defendant Gelman’s affidavit, attached to the Motion. [Doc. No. 17-1, hereinafter “Gelman Affidavit.”]

The party opposing summary judgment and who requests additional discovery must specify by affidavit the reasons why it cannot present facts essential to its opposition to a motion for summary judgment by demonstrating (1) the probable facts are not available, (2) why those facts cannot be presented currently, (3) what steps have been taken to obtain these facts, and (4) how additional time will enable the party to obtain those facts and rebut the motion for summary judgment. Valley Forge Ins. Co. v. Healthcare Mgmt. Partners, Ltd., 616 F.3d 1086, 1096 (10th Cir. 2010)(internal quotations omitted); Been v. O.K. Indust., Inc., 495 F.3d 1217, 1235 (10th Cir. 2007)(The [*12] protection under Rule 56(d) “arises only if the nonmoving party files an affidavit explaining why he or she cannot present facts to oppose the motion.”)

As noted above, the instant motion and the Gelman Affidavit were filed on August 12, 2011. The discovery cut-off date in this case was not until October 3, 2011. (Scheduling Order, [Doc. No. 10] at 6.) Therefore, written discovery could have been timely served any time prior to August 31, 2011. When Defendant filed his motion and the affidavit, Plaintiffs still had nineteen days to compose and serve interrogatories and requests for production of documents in order to obtain substantiation – or lack thereof – of the matters contained in the Gelman Affidavit. Additionally, Plaintiffs had 49 days remaining within which to notice and schedule the deposition of Mr. Gelman, or any other person. Apparently, Plaintiffs did not avail themselves of these opportunities, or, for that matter, any other attempt to obtain discovery during the entirety of the discovery period. There is no reason for the court to now accredit Plaintiffs’ professed need for discovery at this late date when they did not undertake any discovery within the appropriate time [*13] frame even though the issues were then squarely before them. The request for further discovery is denied.

C. Defendant Gelman’s Status as Debt Collector

The court has been presented with the following: the testimony through affidavit of Leonard M. Gelman; the testimony through affidavit of Tracy Hightower (Resp., Ex. 3 [Doc. No. 23-3] “Hightower Affidavit”); the Judgment Order and the Atty. Fee Order of Judge Wayne Patton referenced infra; the Complaint filed in the Summit County case – case number 10 C 255 (Mot., Ex. G); a letter from Lee Gelman to Thomas Henne dated April 1, 2010 (Mot., Ex. D; Resp., Ex. 1, “Demand Letter”); a letter to Lee Gelman from Tracy L. Hightower-Henne dated April 5, 2010 (Mot., Ex. E); an email exchange between Lee Gelman and Tracy Hightower dated April 13, 2010 (Resp., Ex. 4); an undated internet home page of Mountain Law Group (Mot., Ex. F); a document purporting to be a “Colorado Court Database” listing seven cases involving as plaintiff either Summit Interests Inc., Back Country Rentals, or Colorado Backcountry Rentals for the time period March 25, 2009 through November 18, 2010 (Resp., Ex. 7); three letters signed by “Lee Gelman, Esq.” drafted on letterhead [*14] of a law firm named Dunn Keyes Gelman & Pummell with origination dates of March 10, 2008, March 19, 2009 and December 19, 2008 (Resp., Ex. 8); and, the snowmobile rental agreements and other documents relevant to the Summit County case (Mot., Exs. A – C).

The FDCPA regulates the practices of “debt collectors.” See 15 U.S.C. § 1692(e). If a person or entity is not a debt collector, the Act does not provide any cause of action against them. Plaintiffs’ Complaint alleges only violations of the FDCPA (See Compl. [Doc. No. 2]) by Defendant Gelman; therefore, if Defendant is not a debt collector, Plaintiffs’ action must fail.

The FDCPA contains both a definition of “debt collector” and language describing certain categories of persons and entities excluded from the definition.9 Thus, an alleged debt collector may escape liability either by failing to qualify as a “debt collector” under the initial definitional language, or by falling within one of the exclusions. The plaintiff in an FDCPA claim bears the burden of proving the defendant’s debt collector status. See Zimmerman v. The CIT Group, Inc., Case No. 08-cv-00246-ZLW-KMT, 2008 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 108473, 2008 WL 5786438, at *9 (D. Colo. October 6, 2008) (citing Goldstein v. Hutton, Ingram, Yuzek, Gainen, Carroll & Bertolotti, 374 F.3d 56, 60 (2d. Cir.2004).

9 None [*15] of these enumerated exceptions are alleged to be applicable in this case.

The Act defines “debt collector” as:

[A]ny person who uses any instrumentality of interstate commerce or the mails in any business the principal purpose of which is the collection of any debts, or who regularly collects or attempts to collect, directly or indirectly, debts owed or due or asserted to be owed or due another.

15 U.S.C. § 1692a(6). See Allen v. Nelnet, Inc., Case No. 06-cv-00586-REB-PAC, 2007 WL 2786432, at *8-9 (D. Colo. Sept. 24, 2007). The Supreme Court has made it clear that the FDCPA applies to attorneys “regularly” engaging in debt collection activity, including such activity in the nature of litigation. Heintz v. Jenkins, 514 U.S. 291, 299, 115 S. Ct. 1489, 131 L. Ed. 2d 395 (1995). The FDCPA establishes two alternative predicates for “debt collector” status – engaging in such activity as the “principal purpose” of an entity’s business and/or “regularly” engaging in such collection activity. 15 U.S.C. § 1692a(6). It is clear from the evidence that debt collection is not Defendant Gelman’s or his law firm’s principal purpose, nor is debt collection the principal purpose of non-defendant CBR. Goldstein, 374 F.3d at 60-61. Therefore [*16] the court must examine the issue from the regularity perspective. The Goldstein court directed

Most important in the analysis is the assessment of facts closely relating to ordinary concepts of regularity, including (1) the absolute number of debt collection communications issued, and/or collection-related litigation matters pursued, over the relevant period(s), (2) the frequency of such communications and/or litigation activity, including whether any patterns of such activity are discernable, (3) whether the entity has personnel specifically assigned to work on debt collection activity, (4) whether the entity has systems or contractors in place to facilitate such activity, and (5) whether the activity is undertaken in connection with ongoing client relationships with entities that have retained the lawyer or firm to assist in the collection of outstanding consumer debt obligations. Facts relating to the role debt collection work plays in the practice as a whole should also be considered to the extent they bear on the question of regularity of debt collection activity . . . . Whether the law practice seeks debt collection business by marketing itself as having debt collection expertise [*17] may also be an indicator of the regularity of collection as a part of the practice.

Id. at 62-63.

1. Defendant Gelman’s Practice of Law at Mountain Law Group

The testimony of Mr. Gelman provided through his affidavit is considered by the court to be unrefuted since Plaintiffs failed to avail themselves of any discovery which might have provided grounds for contest.

After recounting his background as an environmental lawyer for the Department of Justice, Mr. Gelman describes his practice of law with the Mountain Law Group as an attorney and through the Colorado Office of Dispute Resolution as a mediator. (Gelman Aff. ¶¶ 1, 3.) Mr. Gelman also acts as the manager of his wife’s medical practice. (Id. ¶ 5.) Because of his responsibilities as a mediator and an administrator, Mr. Gelman only spends approximately 25% of his working time engaged in the practice of law through Mountain Law Group. (Id. ¶ 8.) If one considers a normal business day to be nine hours, Mr. Gelman then spends approximately 2.25 hours a day practicing law at the Mountain Law Group. Of that time at the law firm, Mr. Gelman devotes approximately 30% to “Business/Contracts,” the only area of his practice which generates any [*18] debt collection activity. (Id. ¶¶ 8, 22.) Extrapolating, then, Mr. Gelman spends approximately .67 of an hour, or approximately 45 minutes, out of each day pursuing business matters of all kinds for his clients.

One of Mr. Gelman’s business clients is CBR to which he provides legal assistance “with all of CBR’s corporate needs . . . [including] a) contract drafting and consultation on rental agreements, waivers, and other forms; and b) representation concerning regulatory and enforcement matters between the U.S. Forest Service and CBR.” (Id. ¶ 19.) Of all the clients of the Mountain Law Group’s seven lawyers, CBR is the only one who generates any debt collection work at all. (Id. ¶¶ 7, 22, 23.) Additionally, of the seven lawyers, Mr. Gelman, through his client CBR, is the only lawyer to have ever worked on, in any capacity, any debt collection matter.10 (Id.)

10 As noted in the Hightower Affidavit, it is not disputed that, as part of CBR’s employment of Mr. Gelman as their corporate attorney, they requested that he attempt to collect the Henne’s debt.. (Id. ¶ 2.)

Over a forty (40) month period, Mr. Gelman states that he sent only 18 demand letters on behalf of CBR to renters of snowmobiles [*19] who did not pay for damages they caused to CBR’s equipment. (Id. ¶ 20.) This averages out to one demand letter every 2.5 months.11

11 Of course, this does not mean that the demand letters are actually sent on such a regular basis.

In connection with Mr. Gelman’s practice of law with the Mountain Law Group, the court reviewed what is purportedly the law firm’s internet home page. (Mot., Ex. F.) This submission contains no date or retrieval or publication. Therefore, the court can give it little weight. However, as part of the analysis, the court notes that at the time of the internet display – whenever that was – the Mountain Law Group’s home page did not include any advertisement suggesting they provided debt collection services or as had any expertise in the collection of debt.

Mr. Gelman otherwise states that the Mountain Law Group neither owns nor uses any specialized computer software designed to facilitate debt collection activity. (Gelman Aff. ¶ 12.) Further, his unrefuted testimony is that the firm employs no paralegal or other staff to assist in debt collection for the firm. (Id. ¶ 5.)

Plaintiffs, however, assert that Mr. Gelman regularly and frequently pursues debt collection matters [*20] on behalf of CBR, pointing the court’s attention to a document entitled “Colorado Court Database” (“CCD”). The CCD may indicate that CBR or Summit Interests, Inc.12 was involved in seven13 case filings in 2009 and 2010. (Resp., Ex. 7.) None of the cases contained on the CCD indicate whether or not Defendant Gelman represented the named entity, nor do any of the cases identify the other parties. The CCD is in the form of a table with columnar headings, “Name,” “Case,” “Filed,” “Status,” “Party” and “County.” Under the column “Party,” six of the cases indicate “Money” and one indicates “Breach of Contract”; both of these terms are undefined. The court does not begin to understand how “Breach of Contract” for instance, can be a “party ” to a lawsuit. The court is completely unable to ascertain the relevance of this document or what bearing it has on whether or not Mr. Gelman is a debt collector since it does not reference Mr. Gelman or debt collection. The CCD, unintelligible as it stands, is therefore inadmissible and will not be considered for any purpose in the summary judgment proceeding. See Johnson v. Weld County, Colo., 594 F.3d at 1209-10.

12 In the April 1, 2010 demand letter from [*21] Mr. Gelman to Mr. Henne, Mr. Gelman professes to represent “Summit Interests, Inc., d/b/a/ Colorado Backcountry Rentals.” (Resp, [Doc. No. 23-1].)

13 The documents references more than ten items, but several have the same case number.

2. Mr. Gelman’s Debt Collection Methodology

This case involves essentially two communications from Mr. Gelman: the April 1, 2010 letter to Mr. Henne and the April 13, 2010 email from Mr. Gelman to Mrs. Hightower-Henne following her letter professing to represent Mr. Henne. (Compl. ¶¶ 21-23, 25, re: Demand Letterl and id. ¶ 24, re: April 13, 2010 email.)

a. Debt Collector Preface

In the April 1, 2010 letter, Mr. Gelman represented that “[t]his firm14 is a debt collector” and in the April 13, 2010 email, under his signature block, was the notation, “This is from a debt collector . . .” The court notes that the warning on the bottom of the April 13, 2010 email does not appear to be part of the normal signature block of Mr. Gelman, because it does not appear on the short transmission at the beginning of the email string wherein Mr. Gelman advised “Tracy,” that he just left her a voice mail as well. (Resp. at Doc. No. 23-4.) This email warning, therefore, appears [*22] to have been specifically typed in for inclusion in the lengthy portion of the email.

14 The letterhead on the communication is “Mountain Law Group.” Mountain Law Group is not a defendant in this action.

Mr. Gelman states he has mediated a large number of debt collection disputes and is therefore “relatively familiar with the collection industry.” (Gelman Aff. ¶ 11.) While the court considers the language used by Mr. Gelman – commonly referred to as a “mini-Miranda” or the “debt collector preface” – as “some” evidence to be considered in the debt collector determination, it is not particularly persuasive standing alone. First, setting forth such a debt collector preface does not create any kind of equitable estoppel. Equitable estoppel requires a showing of a misleading representation on which the opposing party justifiably relied which would result in material harm if the actor is later permitted to assert a claim inconsistent with the prior representation. Plaintiffs have offered no evidence to support a claim that they detrimentally relied upon the debt collector preface. See In re Pullen, 451 B.R. 206, 210 (Bkrtcy. N. D. Ga. 2011).

When attempting to collect a debt, the court applauds [*23] a practice whereby the sender recognizes itself as a debt collector in a mini-Miranda warning regardless of any legal requirement and considers such an advisement prudent and in the spirit of the FDCPA. This course of action would be expected of an attorney such as Mr. Gelman who frequently is in a position to mediate debt collection disputes. However, calling oneself a rose, does not necessarily arouse the same olfactory response as would a true rose.

b. Use of Form Letters